‘Very dangerous situation’ as California braces for 80-mph winds, major fire risk

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — In 1991, flames swept into the Oakland and Berkeley hills, killing more than two dozen people and destroying more than 2,000 homes.

In 2017, the Tubbs fire devastated wine country, killing 22 people and eventually destroying more than 5,000 homes.

Last year, it was the Camp fire, the most destructive in California history, that left 86 dead and more than 13,900 homes destroyed, along with much of the town of Paradise.

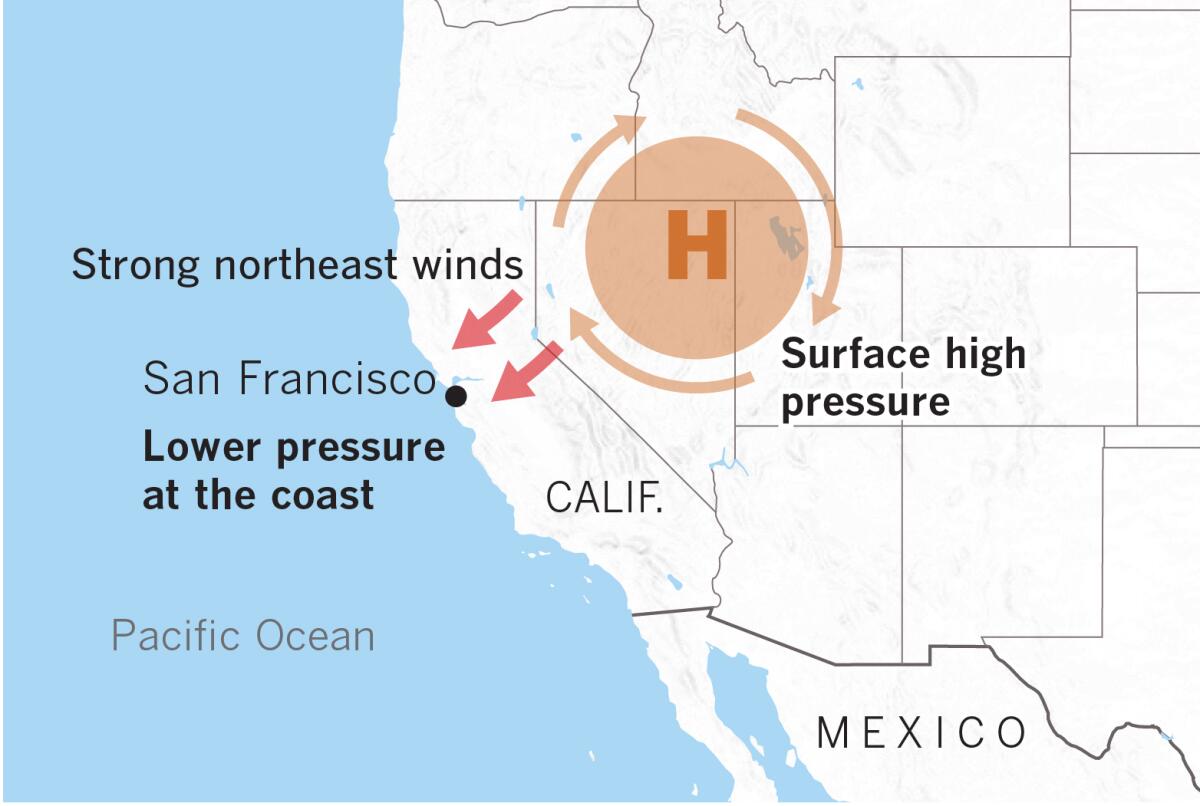

Powerful downslope winds heading from the northeast to the southwest fanned all three firestorms. Forecasters now say these winds that are hitting Northern California this weekend could bring one of the most potentially dangerous periods of fire weather experienced by the region in a generation.

That danger has prompted Pacific Gas & Electric Co. to begin shutting off power to millions, a relatively new and controversial strategy aimed at reducing the risk of fires triggered by electrical lines like the ones that caused the wine country and Paradise infernos. Also Saturday, about 90,000 more Sonoma County residents, from Healdsburg to Bodega Bay and the Pacific Coast, were ordered to evacuate.

The duration of the extreme wind event, known in the Bay Area as Diablo winds, was forecast to be roughly 36 hours, from Saturday evening around 8 p.m. into Monday morning, with isolated gusts of 65 mph to 80 mph in the highest peaks in the North Bay.

Weather forecasters hope that no sparks will ignite major destructive wildfires, but the potential for swift-moving wildfires is high.

“This is definitely an event that we’re calling historic and extreme,” said David King, meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Monterey office, which manages forecasts for the Bay Area. “What really sets this apart from 1991 and 2017 is the time that these winds are going to continue gusting above 35 miles an hour…. The fact that this is going from Saturday night all the way to Monday morning, that’s what is really making this historic.”

Not only will winds be bad, but the air will be quite dry — relative humidity levels are forecast to fall between 15% and 30%; anything in the teens and 20s is really dry, King said.

“It’s certainly going to be a potentially very dangerous situation,” said Jan Null, adjunct professor of meteorology at San Jose State. “We are at the driest time of the year — if a fire starts with this dry, very strong wind pattern, the spread is extremely rapid.”

Temperatures are forecast to drop from midweek levels, which reached the 90s as the Kincade fire burned out of control on the northern edge of Sonoma County, destroying dozens of structures; in the North Bay, highs were forecast to fall into the 80s on Saturday and the 70s on Sunday, said weather service meteorologist Anna Schneider. But the falling temperatures won’t make much difference; the hot weather this week just dried out vegetation even more.

The area of highest risk includes the San Francisco Bay Area and points north, among them the northern Sierra Nevada and California’s North Coast region, including such cities as Eureka, said Daniel Swain, a climate scientist with UCLA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research. It’s been particularly unusual that the North Coast has been so dry at this point in the fall, Swain said.

“This is the kind of event that makes me personally nervous, as somebody who has friends and family living in the fire zones in the Bay Area, and I don’t say that about all the events,” Swain said. “Hopefully, we get lucky and there are no major ignitions. But if they happen, it’s going to be really hairy Saturday night and Sunday. It’s looking really, really extreme.”

The winds are perhaps strong enough to cause some wind damage, perhaps even in some of the lower elevation regions, Swain said. Though it’s not unusual to see strong gusty winds in the hills and river canyons in Northern California in the autumn, this one is unusual for blowing strong winds in places where a lot more people live: in valleys and near the coast, Swain said.

“These winds are going to be much more widespread, certainly than during previous events this autumn, but also more widespread than is typical during offshore wind events,” Swain said.

PG&E has called some of this fall’s past winds extreme when that wasn’t necessarily the case, he said, but “this one really is meteorologically extreme.”

“Hopefully, the message is getting out there that this event is not like the others we’ve seen recently, and probably is comparable in a lot of ways to what we saw in October 2017 during the North Bay firestorm,” Swain said. “In some ways, this could even be more widespread than that one because there are strong winds expected to extend across an even broader region of Northern California.”

Highly populated areas will probably see winds of about 40 mph to 60 mph in the middle and lower elevations where most people in the Bay Area live, Swain said.

“It really comes down to the time of year: These [winds] are not associated with a nice winter storm system bringing precipitation,” Swain said. “These are going to be dessicatingly dry winds from land to sea.”

It’s not just the hills in Napa and Sonoma counties and the East Bay that are at high risk, as is more typical; the forecast is also bleak for Marin County and the Santa Cruz Mountains, Swain said.

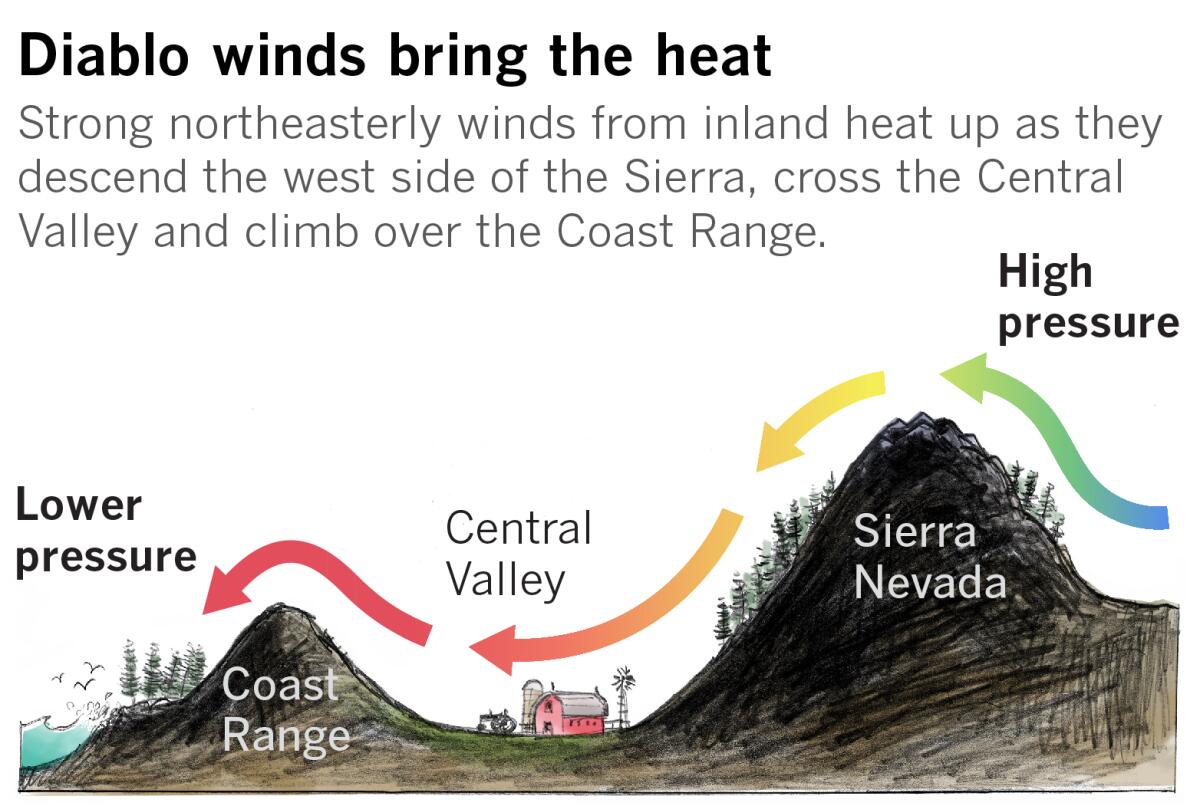

The Diablo winds coming to Northern California this weekend are meteorologically identical to the Santa Ana winds of Southern California. Both come from the northeast and are fueled by high-pressure air over Nevada and Utah seeking a path through the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges or Transverse Ranges to fill lower-pressure voids on the coast.

Not only is dry desert air blowing into California but also, as the air descends in elevation, it warms and the relative humidity plummets, Swain said. And in extreme events, exceptionally dry air can be pulled from the stratosphere and worsen fire weather.

California is no stranger to extreme bouts of fire weather in recent years. A 14-day red-flag event in Southern California from Dec. 3-17, 2017, broke records; the Thomas fire — the 10th-most destructive fire in modern California history — began in Ventura County a day later but exploded in growth more than a week after it started as it raced toward Montecito. That was the longest sustained period of fire weather warnings on record.

Santa Ana wind conditions eased in Los Angeles and Ventura counties Friday afternoon, but forecasters warned of new Santa Ana events starting late Sunday, with isolated gusts of up to 60 mph, and again beginning Wednesday, with peak gusts of up to 70 mph. Minimum humidity could drop as low as 3%, returning critical fire weather conditions to Southern California.

It’s unclear how long this fire season will last in California.

Drier autumns and later starts to autumn rainstorms — which are expected in a future affected by climate change — have compounded wildfire risk in California for the last two years. Firefighters historically have relied on early rains to ease the threat from the land-to-sea winds that can start as early as late September.

The outlook looks dry for the next week and a half.

Times staff writers Joseph Serna and Paul Duginski contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.