The spa-like atmosphere of ‘calming rooms’ help students find peace in turbulent times

- Share via

This is the Feb. 7, 2022, edition of the 8 to 3 newsletter about school, kids and parenting. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox every Monday.

When I conjure the image of a typical public school — the bright fluorescent lighting, the hard, unyielding plastic desk chairs and the shrill bells that announce the beginning and end of class — the word “calming” doesn’t exactly come to mind. Combine that with the frenetic energy that comes with 15 to 30 students crammed into a relatively small room all day, and you’ve got a recipe for overstimulation.

Teachers do the best they can. But for the most part, classrooms aren’t conducive to relaxation, and students historically haven’t gotten much of a reprieve from the sterile institutional environment during the school day, apart from P.E.

A growing number of schools across the U.S. are trying to change that by creating so-called wellness centers (alternately called calming rooms) that give students a place to take a break when they’re feeling overwhelmed. They’re often characterized by plush seating, water fixtures and soft lighting.

Tracy Mendez, executive director of the California School-Based Health Alliance, tells me she has recently seen a “mini-explosion” of such wellness spaces in schools, though the concept has been around for a while and has gained traction over the last few years.

Mendez credits “the growing awareness of neurological functioning and trauma, and the importance of emotional regulation,” as well as the mainstreaming of mindfulness practices. Calming rooms can be part of a layered approach to addressing the youth mental health crisis, especially at schools where a disproportionate share of students may be struggling with pandemic-fueled depression, anxiety and grief. And they’re relatively cost-effective.

I wanted to showcase one of these spaces, so I reached out to the Garden Grove Unified School District. The district has calming rooms in 10 schools — all established this academic year — and is planning more through a partnership with the Orange County Department of Education and Children’s Health of Orange County.

The wellness room at John Murdy Elementary School in Garden Grove is like a spa lobby for kids: plants in every corner, plush carpet and pillows in various shades of blue, string lights and wicker baskets full of blankets and yoga mats. There’s a low table with a rainbow of art supplies, patterned cushions and soft music playing in the background.

“The Retreat” opened at the start of the school year as part of a larger initiative by Garden Grove Unified. Classes got a tour of the space in the first weeks of school, and every group of kids was told the same thing, said Principal Marcie Griffith: Stress is a normal part of life, and sometimes everybody needs a little extra bit of help in dealing with that. This is a special room to help us find our peace.

Murdy is a Title 1 school and serves many low-income families. Students have lost family members, including parents, to COVID. Kids are coming to school with a lot of stress, and little problems (like not finishing a homework assignment) can trigger meltdowns. Demand for counseling has gone way up.

“The stresses at home are high for many of our kids,” Griffith said.

Students from first to sixth grades mostly use the Retreat (formerly a parent resource room) before school, during recess and at lunchtime. These are high-anxiety times of day for many kids, whose social skills aren’t as sharp after being at home for over a year. The room is also available to students who, for one reason or another, have become overwhelmed in class and their teachers have been unable to calm them.

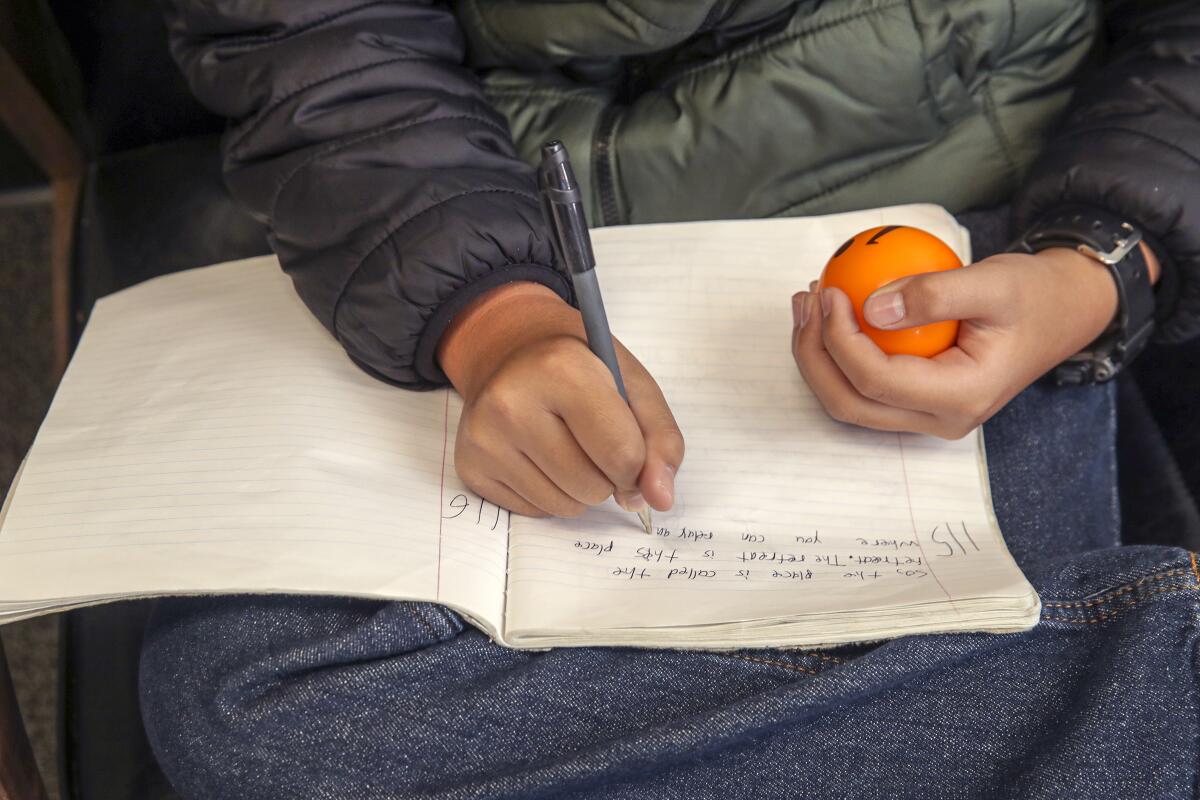

Specialists and other staff supervise the Retreat, and are there to walk students through coping strategies, such as mindful breathing. “We talk about stress and energy, and the need to do something with that energy,” said educational specialist Bethany Garcia. Some kids meditate on yoga mats, while others do art, read positive affirmation books or sit on a cushion and squeeze a stress ball. Others may decide that what is calming for them is not inside the room but outside shooting hoops. It’s all about figuring out what works for them.

The room saw a lot of traffic at the start of the school year. One student, whose mom had recently had a COVID-19 exposure and was quarantined at home, became inconsolably upset when her classmates took off their masks to eat at lunch. A staff member led her to the Retreat, where she was able to calm down.

Jeff Layland, Garden Grove Unified’s supervisor of social-emotional well-being and mental health, noted that calming rooms give students some control and choice in how they are being supported. “We’re giving power and a voice to students when they’re not feeling well emotionally,” he said, “rather than just telling them that they’re going to see a counselor.”

The ultimate goal is that students will take these calming strategies and use them in the playground and at home, Griffith told me. But it also helps staff identify kids who need counseling and otherwise may have flown under the radar.

Fewer kids are visiting the room as the year goes on. Griffith and Garcia take that as a good sign. “Ultimately,” Griffith said, “we want kids to be able to regulate their own emotions.”

Stressed teachers and staff have used the space, too, including Griffith. During the first week of school, she sat on a cushion against the wall, breathed deeply and told herself, “I’m going to make it through this day. I’m going to make it through this day.”

The calming rooms cost from $10,000 to $20,000 each, Layland said (though one being planned at a high school will cost more than $40,000). Most schools are using a blend of money from their general fund, pandemic relief funds and parent-teacher organization donations. It also requires some buy-in from staff who have mental health expertise, as those are the folks who are usually supervising the spaces.

“It’s something I’m extremely proud of, our ability to move both financial resources and staff resources to support our kids,” Griffith said.

Achievement gaps, preventing school dropout and more

Segregation along socioeconomic and ethnic lines has worsened across the country over a 15-year period, contributing to widening achievement gaps, my colleague Howard Blume reports. The trend is particularly concerning in light of other research indicating that students from low-income families make less academic progress as they “come to dominate district enrollments,” said study director Bruce Fuller, a professor of education and public policy at UC Berkeley.

The yellow school bus has become an increasingly rare sight in California. But new legislation is aiming to change that, a policy shift that proponents say could curb absenteeism and narrow inequities, according to Times writer Mackenzie Mays. The bill, sponsored by state Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley), would provide state funding for daily transportation for all of California’s 6 million K-12 students starting next year, alleviating the financial burden for districts. Federal data show that fewer than 9% of California’s students ride a school bus, the lowest rate of any state.

Many parents with disabled or sick children struggle to get the home healthcare they need. The problem is a shortage of nurses, Emily Alpert-Reyes writes. And if there’s no nurse, “we really just don’t get any sleep,” said one mom, Jennifer McLelland, a member of the advocacy group Little Lobbyists. The problem was bad before, she said; it’s worse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

California Community Colleges have moved to permanently adopt a more forgiving pass/no pass grading system — a transcript lifeline of sorts designed to prevent students from dropping out, Colleen Shalby writes. Students will have until the last day of instruction before finals to decide whether they want a letter grade or a pass/no pass credit to protect their GPA. They can also opt for an “excused withdrawal” for coronavirus-related hardships to avoid a transcript penalty.

Students were alarmed by UCLA instructor Matthew C. Harris’ behavior long before he was arrested Tuesday, after he allegedly sent out mass-shooting threats and other disturbing material. The philosophy lecturer had gained a reputation as odd and quixotic, speaking haltingly, changing his syllabus willy-nilly and spending the first four weeks of his “Philosophy of Race” class without once showing his face over Zoom. Eventually, one student said she reported Harris to campus authorities and the FBI, after he directed another student to his YouTube channel, which included disturbing references to sexual perversion and bomb threats at LAX.

Enjoying this newsletter?

Consider forwarding it to a friend, and support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

Did you get this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every week.

What else we’re reading this week

Oakland teachers began a hunger strike after the city’s public school officials presented the school board with a fast-track plan to close and merge more than a dozen schools. Nearly all the schools serve low-income students of color. San Francisco Chronicle

Promises to make high-quality tutoring available to struggling students have proliferated, and a new study shows positive (though modest) results from an experimental tutoring program pilot that launched last spring. But a shortage of qualified tutor candidates raises the question of whether it can be offered on the scale that some advocates envision. The 74

There have been at least 141 shootings at schools so far in the 2021-22 school year, more than at any point in the last decade, according to Everytown for Gun Safety. Experts worry that staff shortages will make it even harder to identify students who could be heading toward violent behavior. Reuters

A conservative student at the University of Mississippi Law School decided to take a class on critical race theory. In two weeks, she learned there were activists and academics who were critical of school integration and the way it had been enforced. She gained a new perspective on racial progress in America. And she still had a whole semester left of issues that no longer felt intimidating but urgent to learn — implicit bias in policing, affirmative action and reparations. Mississippi Today

I want to hear from you.

Have feedback? Ideas? Questions? Story tips? Email me. And keep in touch on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.