8 to 3: Why friendship is hard for many teens right now

- Share via

This is the Oct. 25 edition of the 8 to 3 newsletter about school, kids and parenting. Like what you’re reading? Sign up to get it in your inbox every Monday.

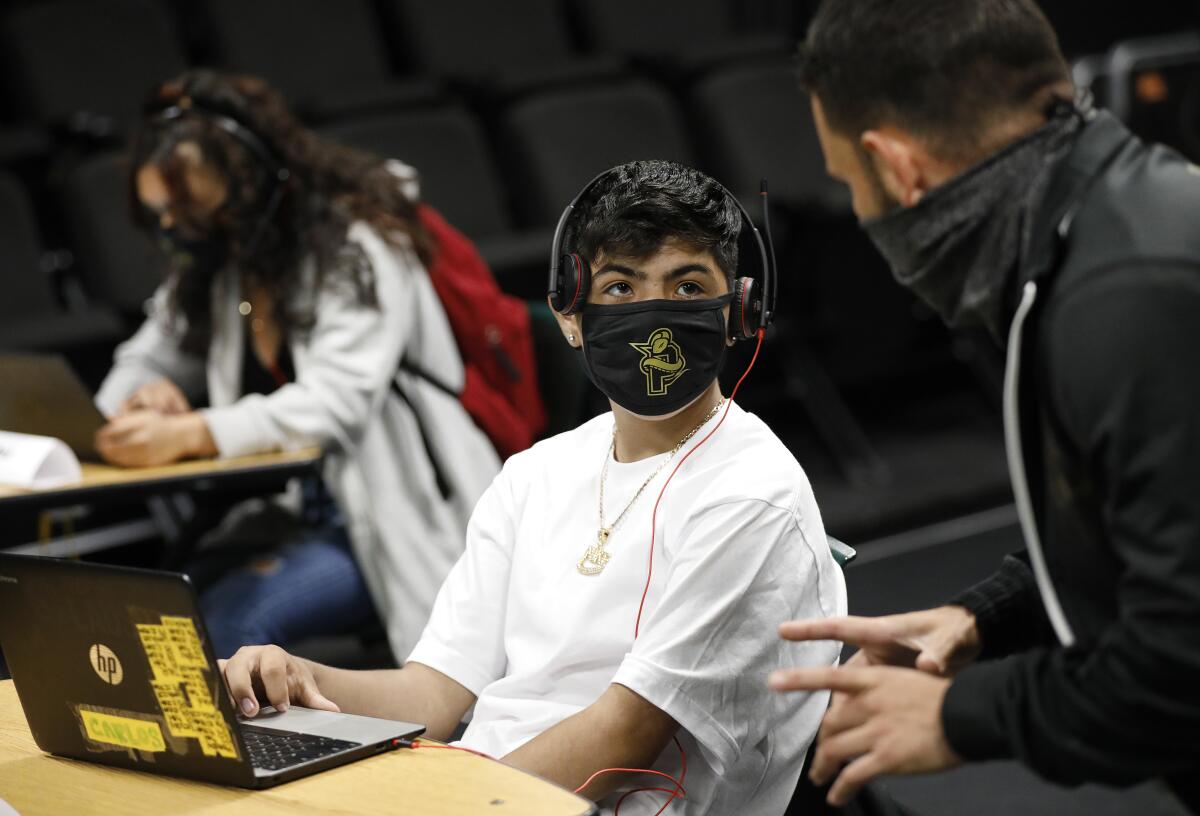

High school counselor Dylan Ohara has watched a troubling pattern emerge as students settle into the school year.

After spending most of their time at home for a year and a half, many kids simply don’t know how to act around their peers. Antisocial behavior has manifested in various ways, with physical fights on one end of the spectrum. Younger students especially have had difficulty breaking into friend groups that have become more exclusive during the pandemic (kids have become more protective of what they have, Ohara observed). Some feel so anxious, so alone, that they barely come to campus.

“We’re seeing this need to really go back to the basics when it comes to helping students understand what healthy intimate relationships look like,” Ohara, who works at Skyline High school in Oakland, told me in an interview this week. “The social drama is just so incredibly amplified beyond anything I’ve ever seen.”

I wasn’t surprised to hear that many teens are struggling socially right now — this was echoed by other educators I’ve interviewed, and academics are starting to track the issue. A survey by Harvard’s Saul Zaentz Early Education Initiative’s Early Learning Study found that 61% of parents thought that their child’s social-emotional development had been harmed by the pandemic.

I spoke with psychologists and therapists to help me understand why this is happening and what parents can do to help.

First off, though, I think it’s important to stress that according to the experts, most kids are tremendously relieved to be back at school and have re-acclimated quickly. Even still, educators and therapists are reporting that more teens than usual are socially anxious.

There are a few reasons for this. For one, kids got used to having a ton of free time in the days of distance learning; high school by contrast can be overwhelming.

“There’s just a lot of stimulation happening,” said Rebecca Good, a psychologist who works with kids and teens in Palo Alto. “They’ve spent a year and a half in their room, staring at a screen, not talking to a whole lot of people. Now they’re navigating crowded hallways, different classrooms, and picking back up on all the nonverbal language they’re not used to reading anymore.”

Relational skills are like muscles that need to be exercised, Good explained. And those muscles inevitably weakened while kids were on lockdown.

There’s the added complication of not being able to read facial expressions — vital purveyors of social cues — when they’re hidden behind masks. “That’s a lot of work that our brains and nervous systems have to do,” Good said.

And there’s the fear of catching and spreading COVID-19. “These kids have been primed to stay away from each other,” said Regine Muradian, a psychologist and children’s author in L.A. “Now you’re putting them back in a classroom with 30 people wearing a mask — of course they’re going to be scared and confused.”

Eileen Kennedy-Moore, psychologist and author of “Growing Friendships: A Kids’ Guide to Making and Keeping Friends,” has another compelling theory about how virtual interactions have altered social skills.

“I am absolutely convinced that 18 months spent staring at themselves on Zoom compounded that self-focus and self-judgment,” she told me. “If you’re constantly thinking, ‘How do I look now? Is she impressed by me?’ It’s like running while looking over your shoulder — you’re looking in the wrong direction. Skillful social interaction requires focusing outwards, attuning to other people’s responses. Kids didn’t have that feedback after months of isolation.”

Therapists told me of teens who are having panic attacks in their cars and crying in their rooms when they get home. They’re unsure of how to start conversations, avoid old friends and extracurriculars, and get into more squabbles. One of Good’s clients dropped out of an in-person college class because the idea of group work was too much to handle.

Compounding the issue is that some teens are feeling more pressure to support their friends at a time when they have limited capacity to do so.

“I have a lot of clients whose friends are self-harming and using substances because of what they experienced during the pandemic,” Good said. “Their friends are leaning on them hard and it’s overwhelming.”

Those who were timid and had a hard time fitting in before the pandemic may feel compounded social anxiety right now, said Jaana Juvonen, a UCLA professor of developmental psychology who studies teen peer relationships. Kids who don’t have many others around them at school who are similar to them — whether it be because of race, sexual orientation, gender expression or socioeconomic background — are also at higher risk.

Teens transitioning to middle school, high school and college are particularly vulnerable because they missed out on crucial social milestones, Juvonen said. Take 10th-graders who are just now setting foot on a high school campus for the first time. They didn’t get to attend summer gatherings or shadow days that are designed to help them make friends and adjust to their new environments.

“We can’t leave kids alone in this,” Juvonen stressed. “We can’t trust that they are resilient and everything will be fine within a couple of months.“

So what should you do if your teen is struggling socially?

“If you notice that your kid is withdrawn, not doing what they used to do, ask them what they’re feeling right now,” Muradian advised. “Speak less, listen more. Validate and normalize their experience. Do not tell them everything is going to be OK, because you’re devaluing how hard this is for them.”

Good recommends encouraging downtime — even watching Netflix or scrolling through TikTok. Pressuring your child to join a million clubs and sports will only burn them out, she said. But too much virtual downtime can be detrimental.

“It’s easy to just scroll on your phone to avoid talking to people,” Juvonen said. “It’s a vicious cycle because kids who are anxious about social interactions are likely to avoid them, and they don’t get the practice they need to get better at them.”

Ultimately, teens need to have in-person fun together outside of school to build strong friendships. Ask your kid if they’d like to have one or two classmates over, and be sensitive to their response. If they aren’t ready yet, that’s OK.

“Tell them to let you know when they are ready,” Muradian said. “Don’t push and don’t get discouraged. But keep the conversation alive.”

The COVID news never stops

Last week, this newsletter focused on “learning loss” — and whether there were dangers in focusing too narrowly on what kids didn’t learn during the pandemic, as opposed to the many things they did learn as they navigated a historic disruption to their lives. Since then, my colleagues Paloma Esquivel and Iris Lee have published an unprecedented data analysis of how the pandemic affected academic learning in L.A., and their results are alarming. They found “deep drops in assessment scores or below grade-level standing in key areas of learning. Black, Latino and other vulnerable children have been particularly hard hit.”

For the first time this school year, a school in Los Angeles County has closed its campus to in-person learning because of a COVID-19 outbreak. Administrators at View Park Preparatory High School, an independent charter school in South L.A., said they acted out of an abundance of caution after 15 students and one staff member tested positive for COVID.

The Food and Drug Administration will decide soon whether to authorize the use of COVID vaccines for children ages 5-11. Early indications are that vaccines are safe and effective for that age group, and it looks likely that they’ll be approved for use beginning next month.

Pandemic got you down? Times travel writer Chris Reynolds takes a look at 18 fun things to do with kids in California this fall. (Why 18? Why not?)

Enjoying this newsletter?

Consider forwarding it to a friend, and support our journalism by becoming a subscriber.

Did you get this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here to get it in your inbox every week.

What else we’re reading

Calls are continuing to defund school police, a movement that has borne fruit in Los Angeles Unified and a few other districts in Southern California. Now activists are turning their attention to school districts in Lancaster and Palmdale, among others. Orange County Register

The pandemic has been hell for PTAs, along with just about every other institution you can think of. Membership dropped by half; many of the activities supported by PTAs vanished. Now some parent volunteers are looking at how they can get back in the game. Sacramento Bee

If your kids go to a California public school and want to maintain kosher or halal diets at lunch, they’re probably going to have to bring food from home. CalMatters

I want to hear from you.

Have feedback? Ideas? Questions? Story tips? Email me. And keep in touch on Twitter.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.