- Share via

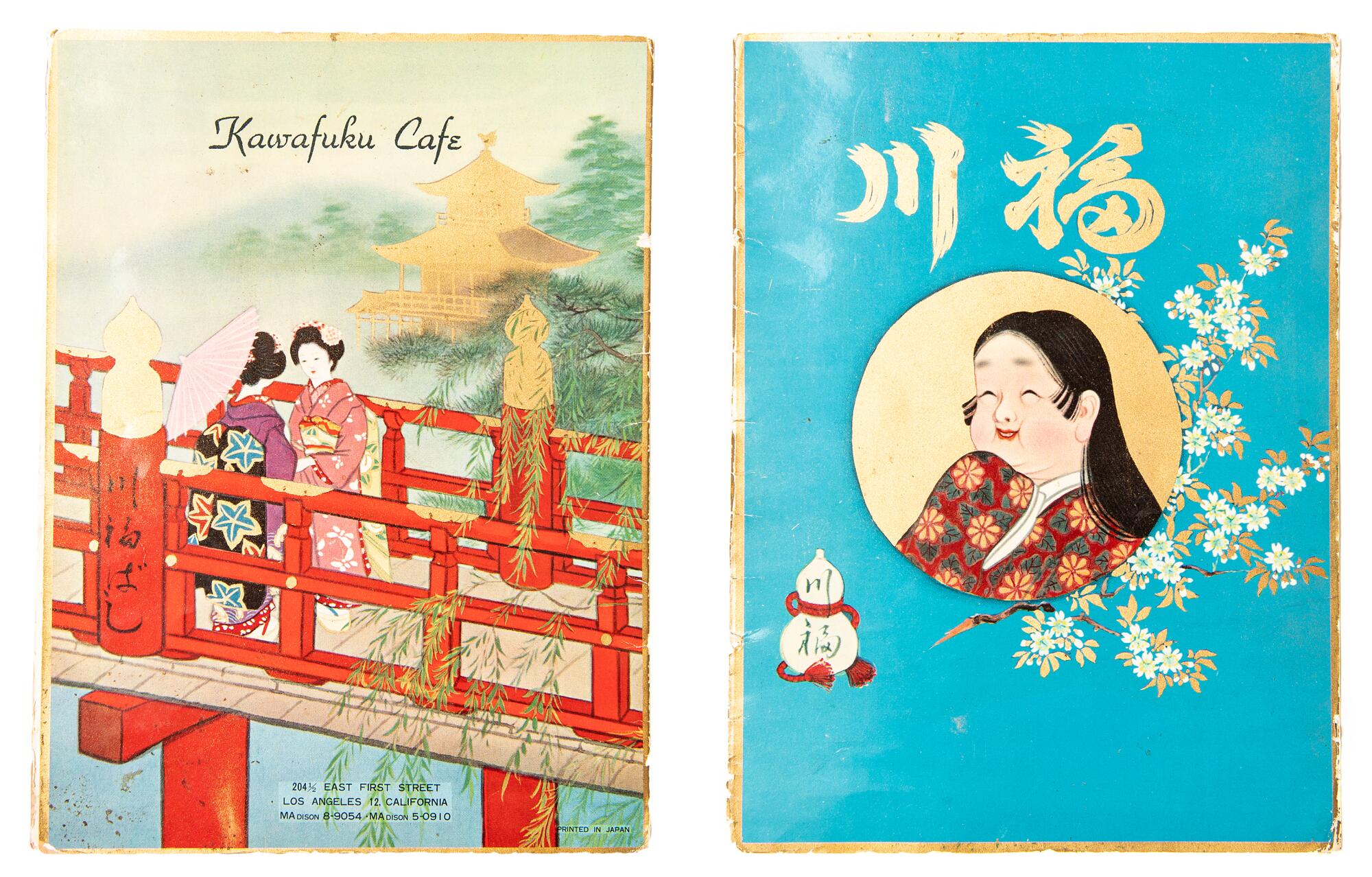

The matchbook flashed like a sunset, its gilt cover catching the light. The promise of candlelight — or maybe a cigarette — was entirely in keeping with the glamorous haunt whose name it bore.

It was a relic from Kawafuku, the Japanese restaurant that had once been the grandest in Little Tokyo.

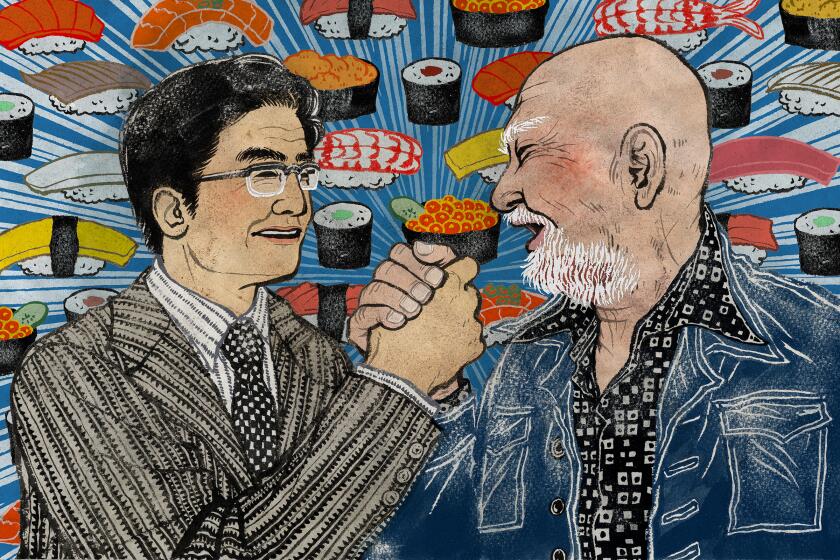

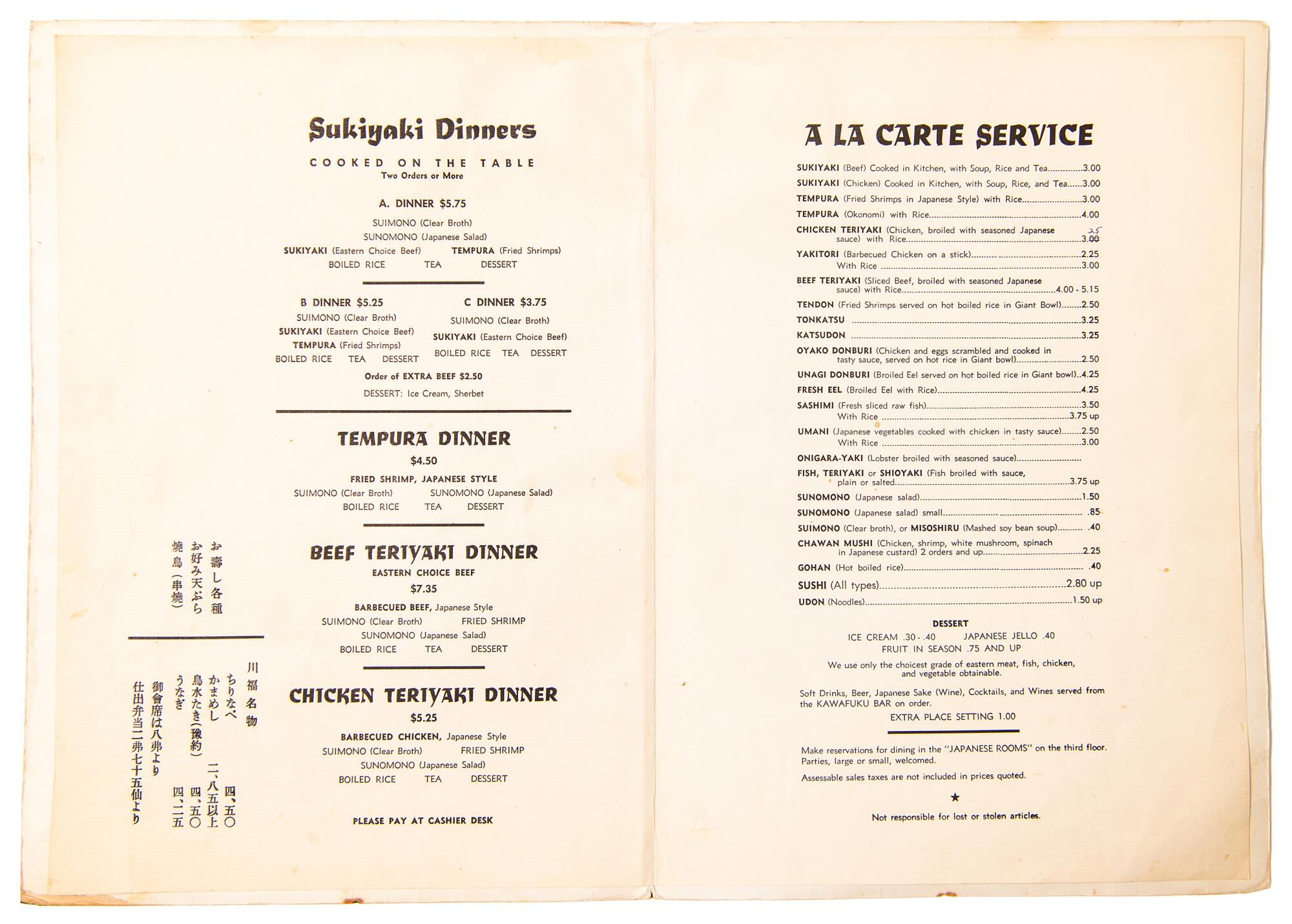

For Angelenos of a certain era, Kawafuku was the place where they first tried sushi — at a small, L-shaped bar installed by its flamboyant owner, Tokijiro Nakashima. He’d done so at the urging of Noritoshi Kanai, the food importer who’d gotten the idea in the mid-1960s to push sushi in L.A. from his associate Harry Wolff Jr.

Kanai and Wolff believed that if Japanese restaurants were persuaded to serve sushi, a lucrative supply chain could be built to support the cuisine — eel, wasabi and all. And Kanai set his sights on Kawafuku, which until then had mostly been known for dishes that were friendly to Western palates. When Nakashima agreed — it took six months to convince him, Kanai said in a 2015 interview with The Times — sushi began its norm-busting journey from culinary curiosity to mainstream Los Angeles offering.

Anthony Al-Jamie, editor in chief of the Japanese culture magazine Tokyo Journal, said that Kanai “couldn’t have chosen a better restaurant than Kawafuku.”

“What better place to try out a new Japanese food concept than in a location where there is already a reputation for good quality Japanese food,” he said.

An unlikely pair of Southern California businessmen paved the way for the sushi revolution in Los Angeles, upending American dining — and their own lives.

Kawafuku was founded by Takichi Kato, who’d been a chef at Japan’s Imperial Palace at the turn of the 20th century. In that role, he regularly cooked meals for hundreds of people, said Becky Applegate, a granddaughter.

“He came to be known,” she said, as “a samurai chef.”

According to Applegate, Kato came to the U.S. after serving in the military for Japan during the Russo-Japanese War, which ended in 1905. He initially settled in San Francisco, where he married his wife, Hana, in 1913. They moved to L.A. about five years later, Applegate said.

The details of Kato’s immigration and his eventual founding of Kawafuku are shrouded in family lore. Applegate said Kato may have been sent to America for a specific reason.

“My husband theorizes that my grandfather had unusual connections, where he may have had help in opening the restaurant,” she said. “He may have been advised to open a … place for [Japanese VIPs] to eat when they got there. And because of his professional history with the emperor and everything, he catered an opulent setting.”

According to most accounts, Kawafuku, which was situated on a triangular parcel bounded by Weller, Los Angeles and 1st streets, opened in 1923. The restaurant quickly became a community favorite. It featured banquet rooms with stages and was known for hosting weddings, said Takako Osumi, another granddaughter of Kato.

The formal cuisine didn’t come cheap.

“If you had your wedding at Kawafuku, it was the best,” Applegate said. “I have heard stories from people, and they said, ‘You know, she had her wedding there and her father was so broke after that.’”

Kato and his eatery were so prominent that when Japan’s Prince and Princess Kaya embarked on an tour of L.A. in 1934, the restaurateur was tapped by movie mogul Louis B. Mayer to stage a banquet for the royals at the Ambassador Hotel, Applegate said.

Because of its grand setting — and perhaps due to Kato’s powerful ties — Kawafuku attracted dignitaries from Japan. Among those to dine there before World War II were members of the Japan Trade Assn. and a former commander in chief of the Japanese imperial fleet, according to Times reports. But some of Kawafuku’s other visitors attracted the U.S. government’s attention.

The current generation of omakase chefs in Los Angeles are returning to the essence of the cuisine. A trip to Tokyo confirms what’s been driving their pursuit for excellence.

A World War II-era report from the House of Representatives’ Committee on Un-American Activities alleged that the Central Japanese Assn., an immigrants’ assistance group that had met at Kawafuku in 1939 and 1940, was actually “an arm of the Japanese Government.”

The report said that the association’s members were “generous in their contributions to Japan’s war chest” and carried out “espionage activities for the Japanese Government.” It listed Takechi Kato as a member of the group’s L.A. branch — and that may have been Takichi Kato.

“It’s not a stretch that he would belong to that” association, Applegate said. “He knew a lot of people. He had connections higher up. They would come to … his restaurant.”

Applegate said that an aunt once translated a Japanese newspaper article about Kato in which he said that Japanese “naval intelligence came to Kawafuku” before World War II.

She also shared a partial transcription of the FBI’s file on her grandfather, a copy of which the family obtained several years ago. The document, dated a few weeks before the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, said that Kato was a member of the Japanese Naval Assn., whose objectives included “the contribution to the development of Japanese naval strength.”

After Pearl Harbor, Kato was arrested, Osumi said. He was imprisoned during the war, and, owing to suspicions about his activity, Applegate said, he was forced to endure a peripatetic existence in “higher security camps.”

From vegan sushi to hand rolls, modest supermarket sushi to high-end omakase — the greater-than-ever scene in L.A. has what you’re looking for.

“They moved him around because of his connections to the emperor,” Applegate said.

By the time Kawafuku opened again in 1946, Nakashima was at the helm.

According to Applegate, her grandparents had already been in the process of “transitioning ownership” of Kawafuku to Nakashima before the war, owing in part to Kato’s health troubles. But the conflict had forestalled that effort. After the war ended, Nakashima reopened the restaurant, she said. Kato died six years later. He was 69.

In Nakashima, Kawafuku had a colorful new owner who wore a Stetson hat and snakeskin boots, drove Cadillacs — including a pink one — and loved to bet on the ponies at Hollywood Park.

A grandson, Derek Arita, remembers that Nakashima — a tall man with a thin mustache — always had a bodyguard in tow wherever he went. “Young muscle” is how Arita described him.

“There was always talk about my grandfather having … Japanese mob connections,” he said, explaining that his parents had mentioned it as a possibility but never provided details. “Was he actually in the mob? We don’t know.”

Nakashima also endured incarceration during World War II. His granddaughter Christina Hara said her family was split up and sent to various detention camps. “He never talked about it,” said Hara, who was a child when she was imprisoned in Wyoming. (Hara died in December; she was 84.)

Under Nakashima, Kawafuku underwent a makeover. Patrons were smitten with the decor, including a reporter for the Los Angeles Mirror. “Your gaze takes in hand-carved wood paneling, tissue-paper bamboo draw drapes and art work done with the fine Japanese touch,” the newspaper reported in 1954.

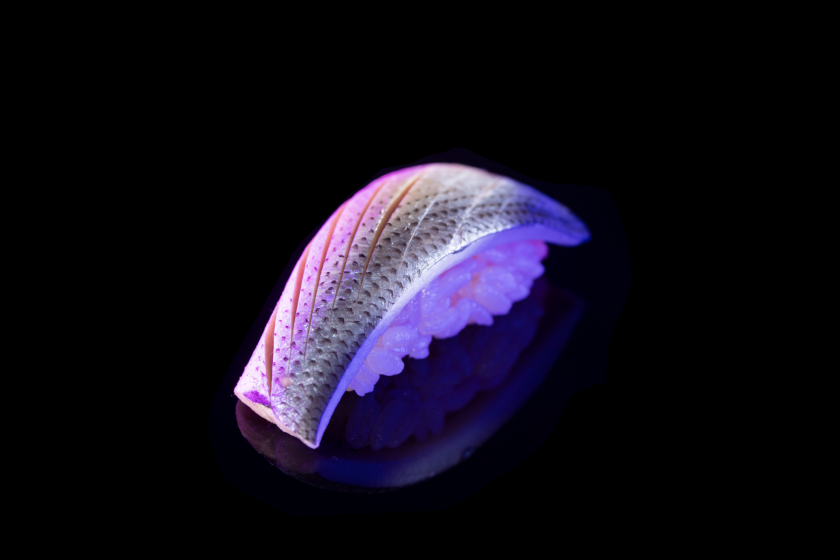

The sushi bar, which featured lacquered wood and a faux roof, was installed on Kawafuku’s second floor around 1965.

“They would hand-make the sushi,” Hara said. “They would almost massage that rice. And if that taste wasn’t there, they wouldn’t serve it,” she said. “The sushi was very good. … It was always busy.”

Before Koda Farms debuted a new strain of rice that would fuel the sushi boom, the family behind it lost nearly everything during World War II.

Nakashima died in 1969, and Hara’s mother took over operations. In 1976, Kawafuku moved to Gardena. But it wasn’t by choice. The restaurant had been forced to leave its Little Tokyo home to make way for a major project slated to be built there: the New Otani Hotel. A story from 1975 in Rafu Shimpo, the Japanese American newspaper based in Little Tokyo, said that the building that housed Kawafuku was owned by L.A.’s Community Redevelopment Agency and would be torn down as part of the $30-million hotel project.

Several other businesses were removed to make way for the development. Ellen Endo, a longtime writer at Rafu Shimpo who covered the saga, said, “There was a lot of turmoil in the entire community.” And the loss of Kawafuku was especially upsetting.

“It was seen as a big deal because, for Little Tokyo, it was a major restaurant,” she said.

They would almost massage that rice. And if that taste wasn’t there, they wouldn’t serve it.

— Christina Hara, Tokijiro Nakashima’s granddaughter

The Times covered the controversy too. In one article, activists labeled the developers “imperialist land-grabbers.”

A gastropub is now situated on the property that once housed Kawafuku.

Served nearly everywhere to sushi lovers, whether or not we should be eating bluefin tuna still is still hotly debated among consumers and conservation experts alike.

In Gardena, it just wasn’t the same for Kawafuku, said Hara, who noted: “It was popular, but not as much as L.A.” The restaurant closed around 1989 and, by then, Nakashima’s descendants no longer operated it.

But you can still find traces of Kawafuku from its heyday in Little Tokyo if you know where to look: EBay. Collectors use the online marketplace to buy and sell ephemera from the restaurant, including matchbooks and menus.

Whenever Applegate comes across items such as a Kawafuku matchbook, she’s sure to check the address and phone number. And when Applegate determines it’s something from her grandparents’ era, she feels “full of joy.”

The mementos transport her back to her childhood.

Applegate remembers a curious thing that would happen whenever she accompanied her grandmother on walks through the neighborhood that once housed her family’s eatery.

It was a gesture from passersby that seemed to acknowledge what the Katos had accomplished at Kawafuku.

“I remember walking around Little Tokyo with my grandmother and people doing the deeper bow,” Applegate said. “The deeper they bow, the more they respect you.”

There were never any words exchanged.

But, Applegate said, “I know it had to come from that.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.