Column: Everyone is thrilled that Medicare can finally negotiate drug prices. Prepare to be disappointed

- Share via

Among the healthcare provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act just signed by President Biden, one shiny object stands out.

It’s the provision allowing Medicare to negotiate pharmaceutical prices directly with drug companies for the first time.

Journalists and some consumer advocates are over the moon about this provision, which has been on Democratic policymakers’ wish list for decades. The healthcare news site Stat called it a “crowning healthcare achievement” for Biden.

There are tons of ways that we already know the drug companies are gaming the system to maximize profit. It’s hard to believe that they won’t creatively find a way around this provision to make it not that effective.

— Simon F. Haeder, Texas A&M

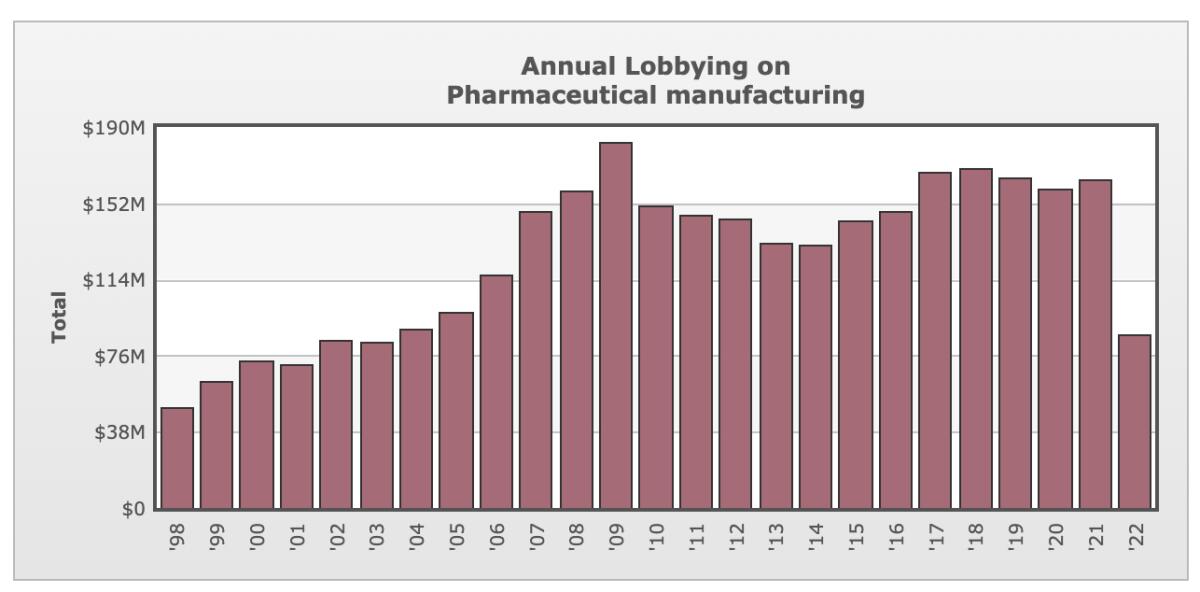

The idea has always garnered overwhelming support among the public, which has interpreted the ban on Medicare’s negotiating authority as a crystal-clear indication of Big Pharma’s corrupt influence over Congress; drug manufacturers spend about $160 million a year to lobby lawmakers and have made about $150 million in campaign contributions to congressional candidates and officeholders since 1990, according to the Open Secrets database.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll last year found 83% of Americans in favor of removing the ban, including 95% of Democrats, 82% of independents and 71% of Republicans.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Sad to say, they’re all likely to be disappointed at the results.

The provision allowing Medicare to directly negotiate drug prices looks powerful on the surface. Medicare is the largest single purchaser of prescription drugs in the country, and prescriptions are the program’s fastest-growing expense.

Medicare accounts for about 20% of all medical spending in the U.S., and about one-third of all spending on prescriptions. So if the program could force drug companies to the table to negotiate prices, that could yield tremendous savings ... theoretically.

But the negotiation provision as enacted won’t have that effect, at least in the near term. It’s pockmarked with loopholes that save the pharmaceutical industry from its most severe potential effects.

Among other flaws, which we’ll get to in a moment, negotiated price changes won’t start to take effect until 2026, and then only for 10 drugs, selected from among 100 accounting for the highest spending by Medicare, and only after they’ve been on the market for many years.

Federal law allows the government to force a huge discount on drugs it funded, but it’s hasn’t claimed its rights on the hugely expensive prostate drug Xtandi.

(The number of drugs subject to negotiation rises to 15 in 2027, 30 in 2028, and 40 in 2029 and later.)

Taken as a whole, the drug price provisions in the act are “a very big deal and a generational victory and critically important,” says Peter Maybarduk, Access to Medicines director at the advocacy organization Public Citizen. “It’s a big setback for Pharma.”

Still, “this does not get us all the way to fair or efficient drug pricing,” Maybarduk told me. “It still lets monopolists sell at the price they prefer for a number of years into a drug’s life.”

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the negotiation provision will save Medicare about $102 billion over 10 years, concentrated in the post-2025 period. Spread over the decade, that sum is the equivalent of about 1.3% of Medicare’s annual spending.

Others point out that the drug industry is spectacularly adept at exploiting regulatory loopholes.

“There are tons of ways that we already know the drug companies are gaming the system to maximize profit,” says Simon F. Haeder, a healthcare expert at the Texas A&M School of Public Health. “It’s hard to believe that they won’t creatively find a way around this provision to make it not that effective.”

It’s true that in its broadest sense, the Inflation Reduction Act is the first measure in decades to place any significant limits on the drug industry’s ability to charge Americans the highest prices in the developed world.

Despite consistent public outrage, the industry hasn’t displayed any inclination to be more circumspect in its U.S. pricing.

A recent study by Benjamin Rome of Brigham & Women’s Hospital of Boston and colleagues found that average launch prices of new drugs increased by more than 20% a year from 2008 through 2021. Some 9% of drugs reached the market with launch prices of $150,000 or more from 2008 through 2013, but 47% in 2020 and 2021.

Column: How the FDA’s lousy judgment and a greedy drug company combined to hit Medicare members hard

The FDA approved an unproven Alzheimer’s drug, and its manufacturer priced it in the stratosphere. Result: Medicare members get higher premiums.

Just this week, the biotech firm Bluebird Bio won Food and Drug Administration approval for a drug to treat a rare blood disease requiring frequent lifetime transfusions, priced at a record $2.8 million, wholesale.

Let’s examine how the negotiation provision is designed to work.

Although the 10 drugs to be initially selected by the secretary of Health and Human Services for negotiation must be drawn from the 50 accounting for the highest spending by the Part D prescription benefit and the 50 costing the most for Part B (mostly doctor services and outpatient care), there are limitations on the secretary’s choices.

Excluded are drugs for which generic or biosimilar alternatives exist, those that have been approved for marketing for only nine years (for conventional drugs) or 13 years (for biotech products), and “orphan” drugs — those that are the only drugs approved by the FDA to treat certain rare conditions.

The delay before negotiations can take place will bring most drugs close to the end of their patent-protected life span, after which generics manufacturers can market the same formulations.

Patents run for 20 years from the date of application, not the date of FDA approval. The FDA can extend the exclusivity period for manufacturers by months or years for drugs in certain categories. This means that a drug can be protected from competition for as little as two to three years, depending on how long it takes to win FDA approval.

Little in the negotiation provision actually gives Medicare all the leverage the program would need to engage in really hard bargaining.

Letting Medicare negotiate with drug companies isn’t the panacea you think it is.

The negotiators are “supposed to negotiate them based on the benefits that the drug provides [and] the likelihood that the drug had already provided a return on investment to the manufacturer,” Aaron Kesselheim, a drug policy expert at Harvard Medical School, said on a recent podcast.

Yet as negotiators in all walks of life know, the best leverage one can have is the ability to walk away from the table.

That’s what allows the Department of Veterans Affairs, the most successful drug price negotiator among federal agencies, to do as well as it does: It’s permitted to drop drugs from its national formulary if it deems them too expensive or not sufficiently effective.

Medicare doesn’t have that latitude. By law, it’s required to cover any drug approved by the FDA.

It’s not widely understood that Medicare already has the right to negotiate drug prices, but only indirectly. Part D rules vest the individual health plans that offer Medicare prescription coverage with the ability to negotiate prices with drugmakers. Medicare as a program is forbidden to “interfere” with the plans’ negotiations — that’s what has kept the program from the table.

The health plans have the ability to walk away, but only within limits. They’re required to provide at least two drugs in each of several drug classes, and “all or substantially all” drugs in six protected classes: immunosuppressant, anti-cancer, anti-retroviral, antidepressant, antipsychotic and anticonvulsant drugs. In any case, as relatively small individual negotiators, they have only limited power to extract bargains from the drugmakers.

The newly enacted act does have a couple of provisions that give Medicare a bit of leverage in pricing talks: A steep excise tax of up to 95% of the annual sales of a given drug imposed on drugmakers that refuse to negotiate. That will keep them at the table, but won’t necessarily force them to come to terms.

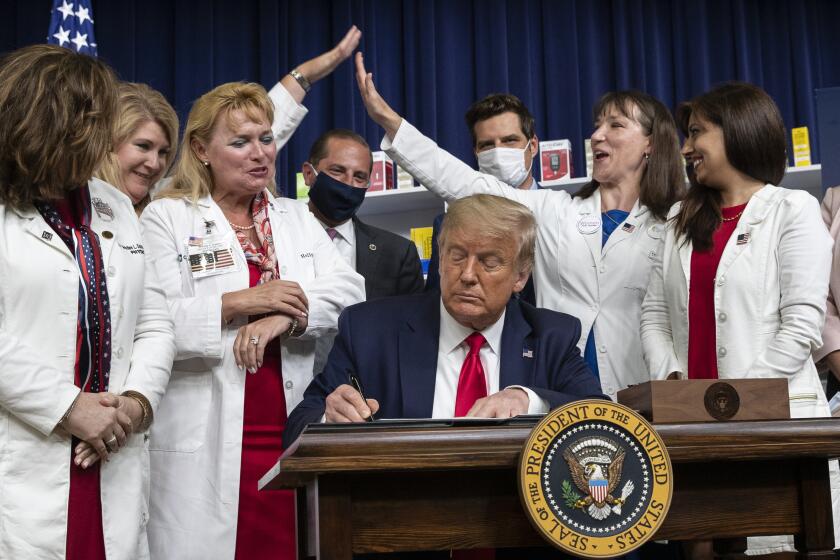

Trump’s drug price strategy was all talk and no action.

The law also sets an upper limit on the negotiated price, based on a percentage of the average selling price in various markets, but it’s unclear whether that would necessarily be lower than what a drugmaker would be inclined to charge in any case.

The measure also requires drugmakers to pay a rebate to Medicare for price increases on many drugs higher than inflation.

Haeder observes that several provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act may produce more immediate and noticeable savings for seniors on Medicare than the negotiation provision. The act limits the annual out-of-pocket spending on Part D pharmaceuticals to $2,000 a year, a distinct gain for the estimated 1.4 million enrollees who have been spending more than that.

It also limits annual premium increases for Part D to 6% a year from 2023 through 2030, eliminates copays for adult vaccines, and caps spending for insulin by Medicare enrollees to $35 a month.

The insulin provision underscores the benefits and drawbacks of the act’s healthcare provisions. The high price of insulin demanded by its manufacturers has been an enduring scandal for years, resulting in patients rationing their own supplies, risking their health, to make ends meet.

The Medicare cap will help an estimated 3.3 million enrollees, but provisions to extend the cap to customers of private insurance plans and the uninsured were stripped out of the bill for procedural reasons.

“No medicine so typifies the treatment rationing and exorbitant pricing crisis that the United States faces as insulin,” Maybarduk told me.

What’s most encouraging about the Inflation Reduction Act’s healthcare provisions is that as a political victory it establishes a foundation for further progress in the fight against drug industry profiteering.

Legislation isn’t necessary; the White House could force prices down or reduce the pace of increases through executive action, by authorizing generics manufacturing to compete with certain high-priced brand-name drugs, using the government’s so-called march-in rights over drugs that have been developed with federal funding — which is most of them.

“Over time, the bill can be expanded,” Maybarduk says. “It can be tightened against gaming. You could expand the list of [negotiated] drugs. It’s a framework that we can keep improving. Because it’s breaking the logjam and allowing the government to get in the game of negotiating prices for the world’s largest drug purchaser, that’s a very significant win.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.