Column: The government could force a price cut for this prostate cancer drug by as much as 80%. Why hasn’t it acted?

- Share via

Xtandi, a wonder drug for prostate cancer, was developed at UCLA with substantial funding from the taxpayers through the Pentagon and the National Institutes of Health.

UCLA has profited handsomely from the drug, to the tune of more than $520 million in royalties. The drug companies that acquired the manufacturing license, including Pfizer and the Tokyo firm Astellas Pharma, have also raked in billions in sales.

American taxpayers and prostate cancer patients haven’t done as well. Xtandi’s average wholesale price in the U.S. comes to $189,800 a year.

If you’re going to develop a drug with U.S. taxpayer funding, that doesn’t give you freedom to charge whatever you want and gouge people.

— Robert Sachs, prostate cancer patient and activist

Prostate cancer is disproportionately a disease of older men, so much of the cost falls on Medicare, which has become the largest single customer for the drug; Medicare spent more than $5.8 billion on Xtandi from its introduction in 2012 through 2019, the last year for which the figure is available. In some years, the drug has been among the top 10 costliest drugs for Medicare.

Deductibles and co-pays can bring the out-of-pocket cost of Xtandi even for Medicare enrollees to nearly $10,000 a year. “For many people who are contending with prostate cancer, that’s real hardship,” says Robert Sachs, a retired telecommunications executive who has been an Xtandi patient.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The drug is so expensive at the wholesale level that private insurers place it in the highest co-pay categories; some won’t allow doctors to prescribe it without their prior approval, further narrowing patients’ access.

The excruciating problem of high drug prices in the U.S. arises from multiple dysfunctions of our healthcare system, including unrestrained profiteering by drug companies, overly indulgent patent policies and the failure of the government to get tough with the pharmaceutical industry.

The case of Xtandi — or enzalutamide, to use its generic name — is a nearly perfect illustration of how these ailments magnify one another.

Accordingly, it has become a test case for the government’s willingness to exploit its legal rights to force drugmakers to slash U.S. prices. Bringing those prices down to the level seen in countries such as Canada, Australia and Japan could reduce spending on Xtandi by as much as 80%.

Column: How the FDA’s lousy judgment and a greedy drug company combined to hit Medicare members hard

The FDA approved an unproven Alzheimer’s drug, and its manufacturer priced it in the stratosphere. Result: Medicare members get higher premiums.

The tools to achieve these discounts are arguably available to the U.S. government today.

Sachs and other cancer patients, supported by the nonprofit consumer group Knowledge Ecology International, have petitioned the Department of Health and Human Services to exercise its legal right to unilaterally license the manufacture of drugs that have been partially funded by the public but that aren’t being commercialized in the public interest.

The agency has hinted that it might make a decision on the request as early as this month, whether by approving or rejecting the petition or scheduling hearings on the request.

HHS rejected a similar petition during the Obama administration, but the political ground may have shifted since then, as frustration with prescription prices has only intensified. In July, President Biden signaled in an executive order that he may be open to more aggressive government approaches to reducing drug prices.

The government’s ability to force drugmakers to bring U.S. prices down, therefore, is now very much in play.

UCLA no longer has a dog in the Xtandi fight: Its sale of the license rights in 2016 ended its role in the drug’s marketing or sales. Pfizer obtained a share of the rights through a corporate acquisition in 2016.

The drug has become a major product for Pfizer and Astellas, so any reduction in the price could have an impact on the companies’ revenues.

Pfizer referred questions to Astellas, which told me through a U.S. spokesperson that Xtandi “is priced in line with other oral therapies for advanced prostate cancer available in the U.S. today and is widely available for patients across the health insurance marketplace.” Astellas, which controls the pricing of Xtandi, has raised the price by nearly 90% over the last eight years, according to calculations by Knowledge Ecology.

Letting Medicare negotiate with drug companies isn’t the panacea you think it is.

The key factor in the debate is the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, which governs the exploitation of products developed with federal funding. Bayh-Dole allowed private companies to commercialize inventions that grew out of federally funded research, but it reserved certain rights for the government to protect the taxpayers’ investments.

Chief among them are “march-in rights,” which allow the government to require that a federally funded drug be licensed to other manufacturers, or to offer a license itself to alternative drugmakers to ensure that the drug is widely accessible, if it concludes that a manufacturer hasn’t taken sufficient steps to make a product publicly available or hasn’t brought it out on “terms that are reasonable.”

The government has never exercised its march-in rights, though it has occasionally threatened to do so to extract concessions from manufacturers. HHS, the NIH and industry lobbyists have maintained that march-in rights were not designed to be used to bring prices down, but that’s disputable.

The debate hinges on how to define “reasonable” terms. The law’s authors, former Sen. Birch Bayh (D-Ind.) and the late Sen. Bob Dole (R-Kan.), maintained in 2002 that the language had nothing to do with “the pricing ... or the profitability of a company” that held a license for a product developed with government support.

Rather, they said, the march-in rights were aimed at cases in which a company hadn’t commercialized the product at all.

But others suggest that the law goes further than Bayh or Dole acknowledged. The obstacle hasn’t been the law’s intent, but the unwillingness of government agencies to exercise it fully in the public interest.

“In general, it’s hard to imagine that price is not a ‘reasonable term,’” says Aaron Kesselheim of Harvard Medical School, the coauthor of a memo to HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra supporting the Xtandi petition.

“You could imagine that there could be a price at which a product was unobtainable,” Kesselheim told me. “Certainly the high prices of drugs these days are causing substantial strains for payers leading to high out-of-pocket costs. That’s relevant to the availability of a drug.”

A biotech firm has halted work on a state-funded disease cure, purely for its bottom line.

Several factors make Xtandi a perfect test case for these issues. One is the enormous discrepancy between its prices overseas and what Americans pay: The $189,800 average wholesale price for a year’s supply in the U.S. is more than 5.5 times the roughly $33,000 cost in Canada or Australia and six times the $31,600 price in Japan.

Another is that the expense falls heavily on federal taxpayers, who have shouldered Medicare’s $5.8 billion in Xtandi spending through taxes, co-pays or higher Medicare premiums.

Furthermore, the U.S. government’s rights to Xtandi are indisputable. Its role in the invention, through the funding provided by the NIH and Defense Department, is cited on each of the three patents covering the drug, which expire in 2026 and 2027. Each states forthrightly that “the Government has certain rights in the invention.”

Such rights are becoming ever more important because the government’s role in biomedical research is growing.

A 2020 study found that “NIH funding contributed to research associated with every new drug approved from 2010-2019, totaling $230 billion.” Much of that may be basic research that doesn’t necessarily contribute to specific new drugs, but Kesselheim and colleagues at Harvard have shown that “publicly supported research had a major role in the late stage development of at least one in four new drugs” approved by the Food and Drug Administration from 2008 through 2017.

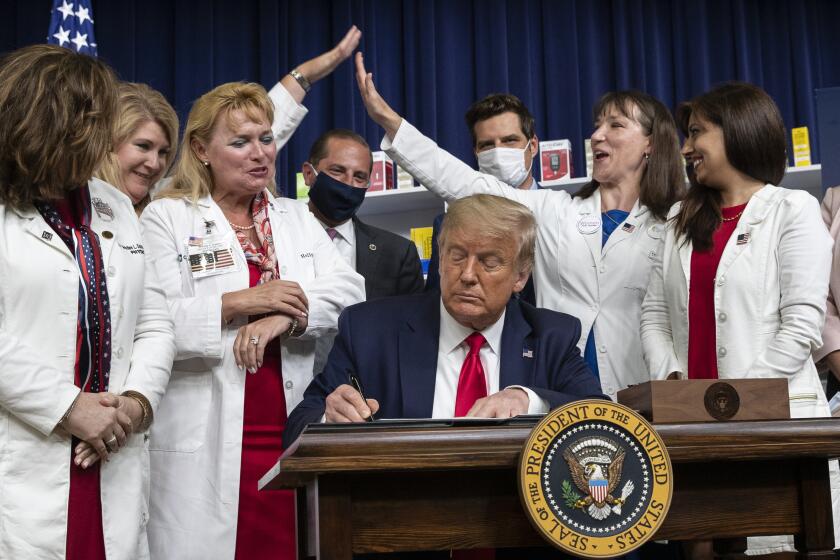

Trump’s drug price strategy was all talk and no action.

March-in rights aren’t the only tool available to the government. According to an analysis published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine by philanthropist Alfred Engelberg, with the collaboration of Kesselheim and Jerry Avorn of Harvard, Bayh-Dole entitles the government to “an irrevocable, automatic license that vests in the government” when it has funded a patented product.

That allows the government to authorize manufacturing by generics firms, which could bring versions at a steep discount compared with the branded price.

Drugs manufactured under the government license may only be used by government programs — Medicare, Medicaid and the Department of Veterans Affairs, for instance.

But that could be enough to provide the government with immense leverage to force Pfizer and Astellas to bring down the U.S. price. As it happens, two companies have already received tentative approval from the FDA to manufacture generic enzalutamide.

The licensing provision can be taken up without the administrative hurdles that the march-in provision might require — “it’s just a matter of the government using this power,” Kesselheim told me.

The NIH has long taken the position that any use of march-in rights or government licensing rights to force prices down would choke off industry collaboration with government science agencies. But that’s scarcely plausible, given the magnitude of public funding.

Indeed, the Xtandi petitioners observed in a recent memo to Becerra that the federal government’s contract with Pfizer for the COVID-19 treatment paxlovid contains a “most favored nation” clause requiring the company to offer the drug to the U.S. at the lowest price charged in Canada, Japan, or five European countries.

The same clause applied to Xtandi would cut its average annual price from $189,800 to about $30,000, the price in Japan.

The government has never directly exploited its Bayh-Dole license rights. But it did use similar rights as a cudgel in 2001, when Bayer, the manufacturer of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin, placed a high price on the drug when the government was trying to build a stockpile for use against potential anthrax attacks. In that case, the threat prompted Bayer to cut its price in half.

Xtandi obviously isn’t the only drug raising the question of whether the public is getting its money’s worth from its billions of dollars in support for the pharmaceutical industry. The petition for march-in rights may face an uphill path.

But Sachs maintains that if the agency at least holds a hearing and “there’s a finding that Astellas has grossly discriminated against U.S. patients, it would send a clear message that if you’re going to develop a drug with U.S. taxpayer funding, that doesn’t give you freedom to charge whatever you want and gouge people.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.