Column: Book-banning is on the rise, as part of the far-right’s assault on democracy

- Share via

Attacks on books occupy a special place among the signposts of philistinism and anti-democratic suppression.

So it’s proper to be alarmed at the upsurge of efforts to ban books from public schools and libraries, largely because they represent political views, lifestyles and life experiences that organized groups characterize as objectionable.

“It’s not that book banning itself is new,” says Jonathan Friedman, director of free expression and education at the free-speech group PEN America. “The biggest trend is the force and the coordination around the country. What’s different is how school districts are giving in to these demands so quickly, in some cases without much due process whatsoever.”

It is not my right to force my beliefs and values on every other parent and their children.... That is censorship, and it has no place in a public school setting.

— Virginia parent Jake Alexander, opposing a local book-banning proposal

Another disturbing aspect is how campaigns to ban books are linked to partisan political goals. “These are deliberate campaigns being waged with the support of political groups ... who use them as a new and promising front in our political and cultural battles,” Suzanne Nossel, chief executive of PEN America, told me.

Nossel ties book-banning campaigns to other efforts to control educational standards — “what we call ‘educational gag orders,’ bans on the teaching of certain topics, essentially to turn back the tide of demographic change in our country.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Local school authorities have been handed lists of scores, even hundreds of books, accompanied by demands that they examine every one for purportedly inappropriate content.

A new Georgia law gives school officials no more than 10 days to respond to a parent’s demand for a book to be removed. Some school officials have been threatened with firing or even criminal prosecution.

Confronted with such possible consequences, some superintendents, principals and librarians simply capitulate. “If anybody brings that kind of case,” Friedman says, “there’s going to be a lot of pressure to simply give in.”

The nexus between book-banning campaigns and political campaigns has gotten stronger in recent years. Recent book-banning demands have erupted in states such as Florida, Texas and Pennsylvania. “They map pretty well to highly contested political territory,” Nossel says.

These campaigns are related to the frenzy over “critical race theory,” a fabricated conflict designed largely to instill fear about the educational system in the conservative political base.

Politicians say they’re concerned about misinformation on Twitter and Facebook, but they’re blowing smoke.

One ad for Republican Glenn Youngkin’s successful campaign for Virginia governor featured a mother who had waged a campaign to ban Toni Morrison’s 1987 book “Beloved” — one of the works for which Morrison won the Nobel Prize, from her son’s school. (Never mind that the book had been assigned to her son nine years earlier, when he was a high school senior — by the time of Youngkin’s campaign he was 27 and an employee of the National Republican Congressional Committee.)

In November, South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster, a Republican running for reelection this year, claimed that “obscene and pornographic” material was being foisted on students in the state schools, and demanded that the state education superintendent perform an investigation and report back to him.

In his Nov. 10 letter to the superintendent, McMaster also objected to the petition process through which parents can file objections to books with their school board, and suggested that school personnel should have kept “Gender Queer,” a graphic novel by Maia Kobabe about her coming out as gay in school, out of their schools without being asked. McMaster declared the book plainly obscene based on “examples” provided by parents.

As if to make explicit his threat of legal action against school personnel, he copied his letter to the chief of the state police.

Preparing for his own reelection bid, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, also a Republican, directed state education officials to weed out “clearly pornographic images and substance” from school materials. As is commonly the case, Abbott didn’t say how those standards should be defined.

Political grandstanders often cast their objections in the context of parental rights to control what their children are exposed to in the classroom or the school library.

That was the rhetoric employed by Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, when he signed the state’s so-called Parental Rights in Education bill, which prohibits lessons in gender identity or sexual orientation unless they’re deemed “age-appropriate.” Critics dubbed it the “Don’t Say Gay” law.

“In Florida, we not only know that parents have a right to be involved — we insist that parents have a right to be involved,” DeSantis said in signing the measure in March.

New York’s Public Theater probably should not have been surprised that Delta Air Lines dropped its sponsorship of the organization following right-wing criticism of its production of “Julius Caesar.”

No one disputes the right of parents to exercise control about what their own children read. The debate is about whether their desired restrictions can be applied to every other child who might take the same class or visit the same school library.

“It’s my right, my duty to help my kids make the best choices for themselves, in accordance with my wife’s and [my] beliefs and values,” Jake Alexander, a parent with children in the Spotsylvania, Va., school district, said at a November 2021 school board meeting. “It is not my right to force my beliefs and values on every other parent and their children.... That is censorship, and it has no place in a public school setting.”

Bowing to objections by Alexander and other parents, the school board voted to rescind an order that the school superintendent screen every book in district libraries for sexual content. Two board members who agreed with the book ban even expressed the desire to burn the challenged books.

Book bans periodically reach the courts, though not recently. The quintessential case, United States vs. One Book Called Ulysses, reached a federal appeals court in 1933, which allowed “Ulysses” to be published in the U.S. on the finding that its occasional use of obscenity and eroticism did not outweigh its unmistakable literary value.

In a 1982 decision involving a New York school board’s decision to remove 10 books from school libraries after they appeared on a list circulated by a conservative group, the Supreme Court overturned the board’s removal of the books, warning that its discretion “may not be exercised in a narrowly partisan or political manner.”

Book-banning in English-speaking countries “has usually been spearheaded by activists inspired by moral panics,” says Kevin Birmingham, author of “The Most Dangerous Book,” a 2014 book about the ultimately successful effort to overturn the banning of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” in the U.S. “One hundred years ago the panics were about candid sexuality and political radicalism. Today they’re about race, gender and identity.”

That’s true, judging from the most recent rosters of the “most challenged books” published every year by the American Library Assn.

The list of all challenged books expanded from several hundred in previous years to nearly 1,600 in 2021. Of the top 10, nine deal with LGBTQ+ or ethnic issues, led by “Gender Queer.”

Many of the challenges suggest an effort to eradicate any viewpoints or historical concepts other than those traditionally considered “mainstream” — that is, white and male. “It’s an effort to assert a certain identity and lifestyle as the norm in education and push other narratives to the sideline,” Nossel told me.

Popular interest in fleeing to Canada after the election of Donald Trump may have ebbed since a surge of inquiries crashed Canada’s immigration website on election night.

That’s why many targeted authors take these campaigns personally, Nossel says — the book-banners are taking aim at “the very purpose of their writing,” which is to “offer kids who may not conform to a certain majority identity a chance to find role models, see a path to their future.”

The banners’ goal is often concealed by their focus on discrete snippets of explicit content rather than the full sweep of an author’s work.

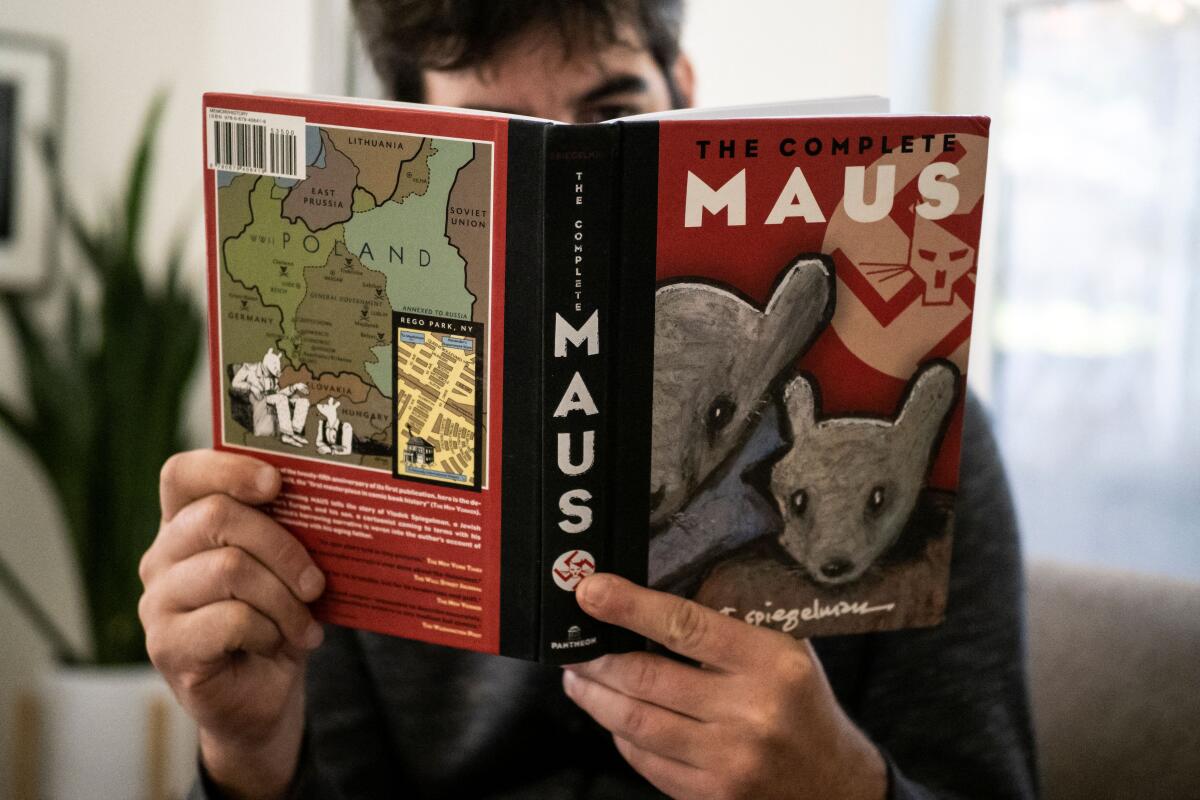

In January, when a suburban school board outside Chattanooga, Tenn., voted to ban “Maus,” Art Spiegelman’s brilliant Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about his parents’ experience during the Holocaust and as survivors, the board cited a smattering of “curse words” in the work and a drawing depicting his mother’s suicide in a bathtub.

“They’re so myopic in their focus and they’re so afraid of what’s implied and having to defend the decision to teach ‘Maus’ as part of the curriculum,” Spiegelman said at the time.

Using selective citations to justify book bans, however, runs counter to the 1st Amendment. “The law does not, and cannot, criminalize the simple isolated passage of a book,” observes Richard Price, a Utah political science professor who runs a blog on censorship. “Instead the dominant theme must be prurient, patently offensive and lack serious value.”

Censors repeatedly assert that “some passage, image, or even single word is so offensive that it must be criminal,” Price writes. “Luckily the 1st Amendment forbids that judgment.”

It’s not unusual for book bans to have repercussions that extend well beyond the specific works being targeted.

When Burbank school officials decreed last year that “the use of the N-word” was disallowed in instructional materials that are required reading, their dragnet encompassed not only “Huckleberry Finn” and “To Kill a Mockingbird” — two of five books that were removed from the school curriculum in 2020 at the instigation of parents, though not from school libraries — but also Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” in which he invoked the word precisely to underscore its demeaning and abusive aspects.

Last week, the Miami-Dade school board, which oversees the fourth-largest school system in the country, left students without a sex education curriculum by rejecting two proposed textbooks for middle- and high schools.

The board was responding to the “Don’t Say Gay” law.

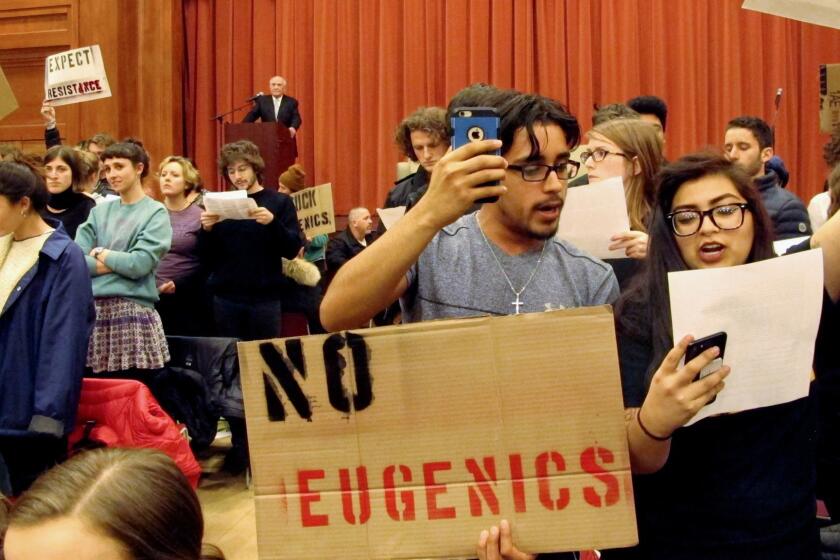

The ugly incident at Vermont’s Middlebury College on March 2, in which a discussion featuring social scientist Charles Murray was ended by hecklers and a professor was injured in the ensuing melee, predictably has triggered a torrent of think pieces about the surge of political intolerance on our college campuses and the desire of our students for “emotional coddling.”

The board’s decision was prompted by complaints by a right-wing parents group, which objected to language in the texts referring to abortion, other forms of contraception, child abuse and the distinction between biological sex and gender identity.

It’s tempting to both-sides book-banning campaigns. After all, it’s said, just as politically motivated groups agitate for the removal of certain books from schools and libraries, book publishers face pressure — sometimes from their own staffs — to refuse or rescind contracts with certain authors. Is there really any difference?

Yes, of course there is — and it’s a qualitative difference. On one side are orchestrated campaigns, often employing government authority, aimed at large categories of works. On the other, objections from people questioning whether a book deal really fits the character that a publishing house is trying to project.

Sometimes a publisher sees things the staff’s way, sometimes not: When staff members of Simon & Schuster objected to that house’s deal with former Vice President Mike Pence, who was closely identified with discriminatory policies aimed at women and members of the LGBTQ+ community, executives decided that the company’s commitment to publish “a diversity of voices and perspectives” outweighed the objections and went ahead with the deal.

Mainstream publishers canceled publication plans for Woody Allen’s memoir “Apropos of Nothing” and Blake Bailey’s biography of Philip Roth because of accusations of sexual misdeeds aimed at both authors; both books soon found a home with Skyhorse Publishing, an independent company that has become known as what The Times described as “a publisher of last resort.”

Those cases are one-offs, targeted at specific books or authors. The right-wing campaigns are mass assaults.

In Texas, state Rep. Matt Krause, who had announced his candidacy for state attorney general, submitted a list of 850 titles to state school boards with a demand that they “disclose if they have these books, how many copies they have and how much money they spent on the books,” the Texas Tribune reported.

What most book-banning campaigns share is an underlying hypocrisy. Their goal isn’t to protect children from what they deem “inappropriate” content, which often amounts to the facts of life; it’s to purge viewpoints that the parents, or the ideological groups they are fronting for, prefer to sweep away in the interest of fostering an entirely unrealistic view of American culture and society.

Who are the victims in this culture war? The children. What they need is to be exposed to divergent and diverse viewpoints because that’s what they are going to find in the real world. They need to be protected not from honest discussions of the real world but from the book-banners.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.