In Burbank schools, a book-banning debate over how to teach antiracism

- Share via

During a virtual meeting on Sept. 9, middle and high school English teachers in the Burbank Unified School District received a bit of surprising news: Until further notice, they would not be allowed to teach some of the books on their curriculum.

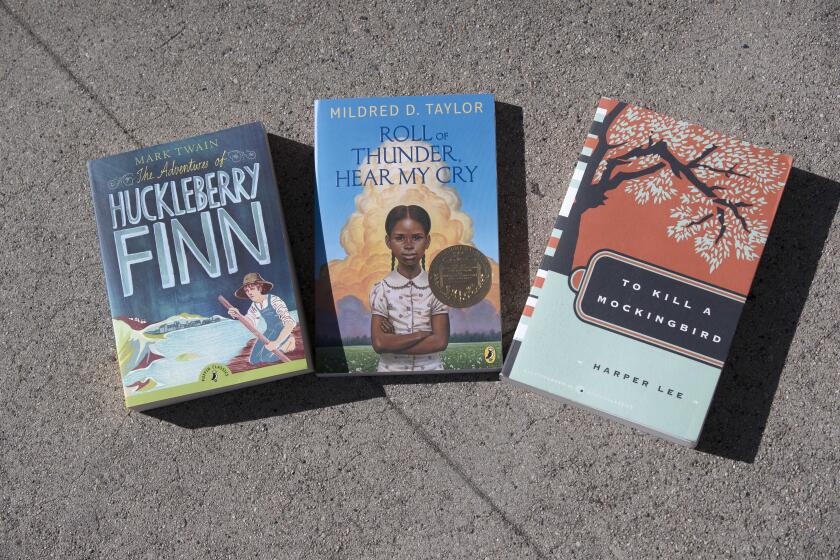

Five novels had been challenged in Burbank: Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” Theodore Taylor’s “The Cay” and Mildred D. Taylor’s Newbery Medal-winning young-adult classic “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.”

The challenges came from four parents (three of them Black) for alleged potential harm to the public-school district’s roughly 400 Black students. All but “Huckleberry Finn” have been required reading in the BUSD.

The ongoing case has drawn the attention of free-speech organizations across the country, which are decrying it as the latest act of school censorship. The charge against these books — racism — has been invoked in the past, but in contrast to earlier fights across the country, this one is heavily inflected by an atmosphere of urgent reckoning, as both opponents and defenders of the novels claim the mantle of antiracism.

The debate within the district comes after a summer of mass protests calling for an end to the unjust treatment of Black people. As a result, many institutions and school districts like BUSD are taking a hard look at themselves, their policies, curriculums and practices, in many cases publishing antiracist statements. And while book banning has a long history in America, the situation in Burbank — once a sundown town that practiced racial segregation — is freshly complicated.

In the abstract, it’s a dispute about the meaning of free speech and who gets heard. More specifically, it’s about what should be taught to the district’s roughly 15,200 enrolled students — who are 47.2% white, 34.5% Latino, 9.2% Asian and 2.6% Black — and how Burbank can move forward on race boldly but sensitively.

Young America’s Foundation announced Monday that it would provide students in the Burbank Unified School District free copies of five books recently removed from the curriculum.

And at its root, it stems from a painful personal story. Destiny Helligar, now 15 and in high school, recently told her mom about an incident that took place when she was a student at David Starr Jordan Middle School. According to Destiny’s mother, Carmenita Helligar, a white student approached Destiny in math class using a racial taunt including the N-word, which he’d learned from reading “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.”

Another time, Helligar added, a different boy went up to Destiny and other students and said: “My family used to own your family and now I want a dollar from each of you for the week.” When the principal was notified, the boy’s excuse was that he had read it in class — also in “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.” Helligar believed the principal was dismissive of the incident.

“My daughter was literally traumatized,” said Helligar. “These books are problematic … you feel helpless because you can’t even protect your child from the hurt that she’s going through.”

Helligar is one of the parents who filed complaints. But as the books were put on hold and the review process inched forward, a diverse group of teachers and students came out against the novels’ removal, arguing that their teaching was essential. A report to the superintendent is due from a 15-member review committee on Nov. 13, but that will only be the beginning of a long debate — in Burbank and beyond.

Essential history or outdated fictions?

A week after teachers learned of the removal, the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) sent a letter to BUSD urging the district to allow teaching of the books while the challenges are under review. On Oct. 14, PEN America released a petition calling for the same.

“[W]e believe that the books … have a great pedagogical value and should be retained in the curriculum,” read letter from the NCAC.

Books written by or featuring people of color are “disproportionately likely to be banned,” said James Tager, PEN’s deputy director of free expression research and policy. “That is a decades-long trend that advocates and observers have seen.”

Book-banning has a long history in America. Such challenges have sometimes been rooted in bigotry. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is cited by many historians as the first book to be banned on a national scale. Published in 1852, it was barred by the Confederacy for its abolitionist agenda.

A century and a half later, Khaled Hosseini’s bestseller “The Kite Runner” was challenged for, among other reasons, allegedly promoting Islam and inspiring terrorism.

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

“Typically these book bans come down from people who are concerned about the books’ challenge to established order,” said Alaina Morgan, assistant professor of history at USC. It’s what makes the situation at BUSD “novel,” she said.

“I think that for Black parents in these districts, there is a very long history of them dealing with microaggressions ... and now they’re seeing their children go through the same things in an allegedly more racially just society,” Morgan said.

Although she believes cancel culture plays a role in the debate, “I think there’s a difference between the gut reaction that cancel culture is — which is people saying, ‘Oh they said something racist they’re [canceled] now’ — and what’s happening here,” she said.

None of the five novels in dispute is openly supportive of segregation or bigotry. All were flagged for words we now find offensive. But the parents’ objections are not merely over language. They also worry about the way these books portray Black history and the lessons they might impart to modern readers.

“The Cay” and “Huckleberry Finn” feature white children learning from the suffering and wisdom of older Black men. “To Kill a Mockingbird” stars Atticus Finch, a white lawyer who defends a Black man accused of raping a white woman. Its white-savior story line reads much differently nearly 60 years after its publication.

“Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” may have instigated Helligar’s complaint, but it is something of an outlier. Narrated by a young Black girl growing up in the South during the Great Depression and Jim Crow era, it’s the only novel on the list by a Black author.

Notably, the BUSD’s reading list hasn’t been revised in three decades. “For over 30 years,” said Helligar, “these books have been on this list. The true ban is that there aren’t other books of other voices that could ever be on there.”

Nadra Ostrom, another Black parent who filed a complaint, agrees that the perspectives are badly in need of an update. “The portrayal of Black people is mostly from the white perspective,” said Ostrom. “There’s no counter-narrative to this Black person dealing with racism and a white person saving them.”

And that, she said, is doing more harm than good. “The education that students are basically getting is that racism is something in the past,” she added. “And that’s not the conversation that we should be having in 2020. … Unless teachers have been specifically trained to teach these texts through an antiracist lens, they are probably reinforcing racism rather than dismantling it.”

Others believe that changed lens is not only feasible but necessary — that the books remain essential to helping frame in-class discussions about contemporary racism. Rather than ban the books, they argue, the district should reevaluate how they’re being taught.

For one Burbank High School teacher who also asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, the Black Lives Matter protests only amplify these books’ relevance.

“‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ was written 60 years ago, and we read it with horror at the unfairness and terrors of a segregated society,” she said. “It’s set in the 1930s, and we look at how things were then and how we feel like we’ve come a long way, but we can note the serious inequities that still exist.”

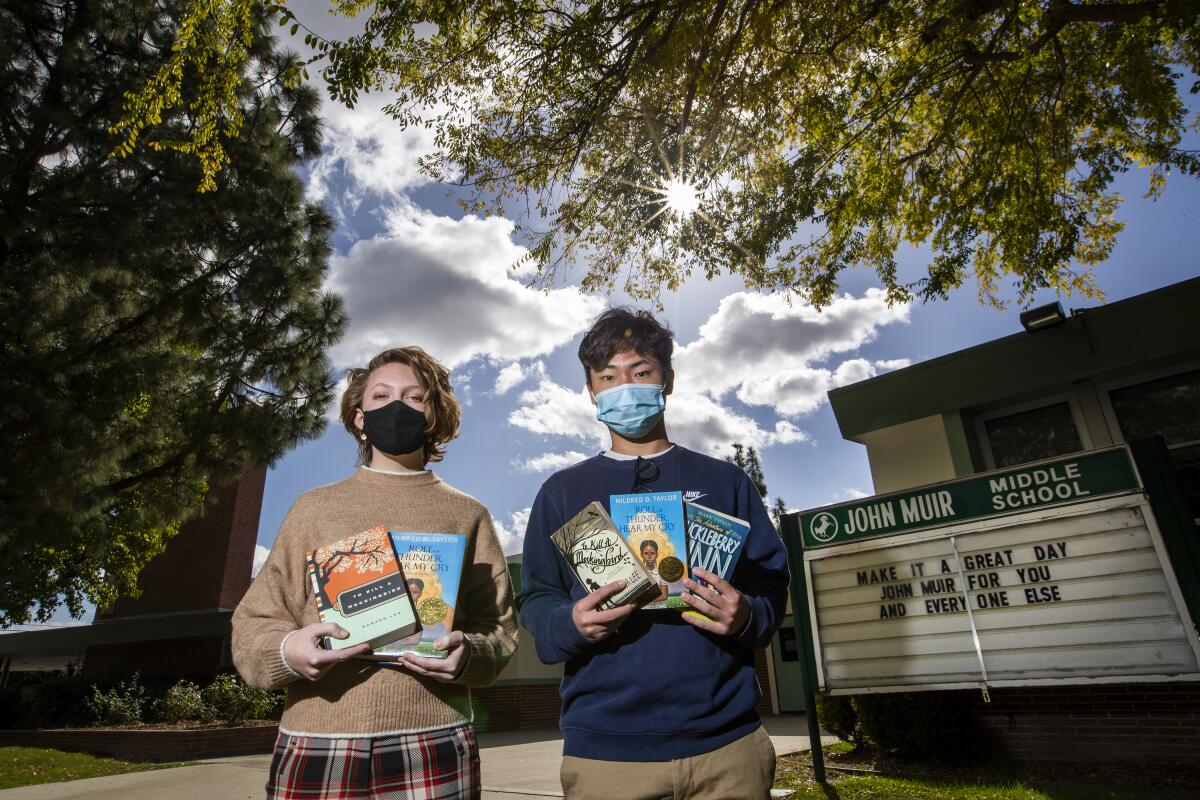

Plenty of district students agree. On Oct. 22, Sungjoo Yoon, a sophomore at Burbank High School, launched a petition to stop what he called a “ban on antiracist books.” As of Nov. 11, more than 2,600 people had signed it. Some 80 students also sent personal statements of protest to district officials.

Yoon, 15, started the petition because he remembered the impact the books had on him. “I didn’t know much about race relations or anything regarding critical race theory when I was younger,” he said, “and when I read ‘Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry,’ that was my first glimpse, and it really did touch me.” He hopes students can continue to have the “breakthrough moment” he did.

From ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ to ‘The Birth of a Nation,’ stories that flatten usually falter

“There are people who have actively been harmed by some of these books in the past,” Yoon acknowledges. “I’ve been in classrooms where teachers, white teachers specifically, unconditionally say the N-word without anybody’s concern or single out a single African American student to become the spokesperson for the entire class. I think that’s where the harm is coming from.”

Chloe Bauer remembers being in tears when she first read “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” in her seventh grade English class at John Muir Middle School.

Bauer, now 14, called the novel her first lesson in America’s “bloody and gruesome” past. When she heard that teachers were told to pause instruction of the book, she felt “confused,” “frustrated” and “saddened.” She thought of her sister, a sixth-grader at John Muir.

So Bauer wrote an email to Sharon Cuseo, Burbank’s assistant superintendent of instructional services, describing her experience. She felt Cuseo’s response was dismissive, so she went to the board of education.

During a Sept. 17 school board meeting, Bauer spoke up: She said the novel had taught her and her peers how “disgusting” the slurs were. “This is an incredibly important lesson to learn at age 13, when seventh-graders are being exposed to music, TV, films and pop culture with conflicting messages about using offensive language, specifically the N-word.”

Helligar doesn’t buy that. She believes the core message being taught is that racism is an artifact of history. “They get to read about racism whereas my children have to experience it. That is the privilege that they get to walk around in.”

She told the review committee that the incidents she reported were themselves proof the books had failed in their mission: “You’re not doing well as an education system if the people you have educated still haven’t learned empathy.”

Some Black parents in the district see both sides of the argument.

Dawn Parker, a Black mother of fourth- and seventh-grade students, empathizes with the parents who’ve complained. “But I think our kids now don’t know how the [N-word] came about, how it was used, the history of it. They hear it in rap music and they think it’s OK to say, and it’s not. They need to know why and where it came from,” she said. They need to learn it in a “safe environment.”

Memoirs by Kiese Laymon and John Edgar Wideman; essays by Darryl Pinckney and Mikki Kendall; masterpieces from Michelle Alexander and Claudia Rankine.

A controversial process

The question of what exactly to do with the challenged books in Burbank has not only divided the community but caused frustration over the district’s procedures for handling complaints.

The process in Burbank can be long and complicated, involving five stages consisting of complaints (formal and informal), an ad hoc committee and multiple appeals. Although it seems to be designed to ensure that parents are heard, the rulebook doesn’t address the core issue of how to improve teaching practices.

Some parents and teachers were initially troubled by the superintendent’s decision to pause instruction of the books before a formal, written complaint was even made. Four official complaints have since been filed. Under district policy AR 1312.2, “challenged material may remain in use until a final decision has been reached,” with children given the chance to opt out from the reading.

Asked why the district removed the books right away, BUSD Superintendent Matt Hill told The Times: “Given the nature of the complaint, the fact that we would have to ask for Black children to opt out of their class and receive an alternative assignment — I did not think that was the most prudent approach. I thought it would be better for us to work together and see if we can get to a resolution.”

It’s only fitting that the 25th anniversary edition of Karen Finley’s “Shock Treatment” (City Lights: 144 pp., $15.95 paper) should come out in time for Banned Books Week, the literary holiday about which I feel most consistently ambivalent.

The five books in question are currently at step four of the district’s process. The review committee has until Nov. 13 to make a recommendation to Hill, who will make a decision that can then be appealed to the board of education. Its last meeting was Nov. 4, but no consensus was reached.

“We are not removing books from our classrooms or schools,” Hill said; they’ll remain in libraries and on optional reading lists. “What we are doing is looking at our reading list and our core novels to identify: Are there concerns with these books? Are these the best books?”

While some teachers and parents believe the superintendent is acting in good faith, they are troubled by the process.

“It seems to have gone directly from an experiences at one of the schools to becoming a district-wide prohibition,” said a Burbank middle school teacher who asked to remain anonymous. He and several colleagues felt excluded from the review. “A lot of teachers were unaware of these concerns and didn’t get the ability to address their practices or ... respond until the decision was made,” he said. He believes the superintendent “did not take steps to include a broader net of parents, students and community members in making this decision.”

It certainly is easier to make top-down, yes-or-no decisions than engage a sprawling school district in the difficult business of how to teach old books in new times. If “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” and the other novels make their way back to the curriculum, the most difficult challenge might be to ensure that students of all backgrounds can find in these books what Bauer and Yoon did.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.