Column: California’s stem cell program found a disease cure, but it’s being blocked by a biotech firm

- Share via

Alysia Padilla-Vaccaro knows she’s been blessed by a revolutionary stem cell treatment that has allowed her daughter Evangelina, 9, to live a normal life. But she’s also anguished.

Anguished not by doubts about the treatment, which was funded with millions of dollars from California’s stem cell program formally known as the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, or CIRM.

The treatment has completely cured Evangelina’s rare genetic immune system deficiency, which is known familiarly as bubble baby syndrome and commonly takes the lives of children with the condition by the age of 2.

Padilla-Vaccaro is anguished because the London biotech company awarded an exclusive license by the stem cell program to develop and market the cure, Orchard Therapeutics, has shelved the development program.

The immediate result has been to deprive other families of the same experience Padilla-Vaccaro has enjoyed with her now-healthy daughter. The syndrome she was born with interferes with the activity of a crucial enzyme, leaving its victims without a functioning immune system and vulnerable to repeated infections.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“Here I am, living this beautiful miracle with my child,” Padilla-Vaccaro told me recently as she gathered up Evangelina and her two other daughters for a visit with the grandparents in Corona, “and these other families aren’t getting it.”

Orchard Therapeutics didn’t shelve the cure because it has any misgivings about the cure’s safety and efficacy — in fact, the company just touted a glowing report published just days ago in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Rather, Orchard says it did so purely for “business reasons,” meaning that it wanted to invest instead in treatments for more common diseases with more potential for profits.

Padilla-Vaccaro has been in touch with other families that have been waiting two years or more for the treatment that saved Evangelina’s life and now may not get it in time to help their children. “It’s heartbreaking,” she says. (Evangelina is not directly affected by Orchard’s action, as she is already cured.)

It’s also costly. CIRM invested some $20 million in the cure, starting in 2016. Most went to UCLA and Donald Kohn of its Broad Stem Cell Research Center, who developed the cure.

The California Institute for Regenerative Medicine is seeking a new $5.5-billion infusion. It must go back to the drawing board.

Orchard says it received $7.2 million from that grant and a subsequent $8.5-million grant CIRM approved in 2018 for clinical trials. Of the latter grant, $5.8 million is still pending. Orchard’s failure to move forward, however, raises the possibility that the tens of millions of dollars in previous funding will have gone for naught.

The Orchard case points to a major dilemma for the stem cell program and an obstacle for its giving the public access to the discoveries it has funded: Although CIRM has doled out almost all the $3 billion in public money it received through Proposition 71 of 2004 and just last November won voter approval for an additional $5.5-billion taxpayer infusion, it doesn’t itself conduct clinical trials of the research it has backed.

That responsibility rests with academic researchers who’ve received its grants or private companies licensed to commercialize the research. They present their trial results to the Food and Drug Administration, which decides whether the treatments have been proved sufficiently safe and effective to offer to the public.

When a private company is involved, however, financial considerations can get in the way. This isn’t the first time that’s happened to CIRM. In the most notable case, CIRM awarded the biotech firm Geron, which claimed to be a leader in stem cell research, $25 million in 2011.

The award was aimed at the first human trial of stem cell-based spinal cord therapy and had been backed by Robert Klein II, the author of Proposition 71 and CIRM’s first chairman, even though CIRM’s scientific advisors were dubious about the proposal.

Six months after the award, however, Geron announced it was leaving the stem cell field completely. It halted its stem cell trial, in which it had already begun treating four patients and was about to start treating a fifth.

The $6-billion California stem cell program, created at the ballot box in 2004, is about to notch a major achievement.

The company returned $6.4 million it had already collected from CIRM. But the ramifications went beyond dollars and sense. The episode raised “major ethical and social issues,” Stanford University bioethicists David Magnus and Christopher Thomas Scott observed in 2014.

It’s one thing to halt a clinical trial of an experimental treatment because new facts have come to light, Magnus told me — the early discovery that the treatment doesn’t work or causes unanticipated health problems, for example.

“There are good reasons for pausing or stopping a trial,” Magnus says. “However, a strictly business decision that has nothing to do with risks and benefits but is a company just saying, ‘We decided to move in a different direction, we’re putting our eggs in a different basket.’ ...To me, ethically, that’s highly problematic.”

The ethical problem extends to the institutional overseers of the trial (in Orchard’s case, UCLA) and the funding institution. In Magnus’ view, both have a duty to hold clinical trial sponsors to the promises.

“I can’t imagine why any funder, state or federal, would ever want to give money to a company that does this,” he says. “Companies aren’t bearing the cost of making those kinds of unethical decisions.”

As it happens, CIRM does have some leverage to force Orchard either to proceed with the cure or to give up its exclusive license — it just hasn’t appeared to exercise that leverage.

Let’s take a closer look at the Orchard case.

California stem cell agency needs to study itself

The disease at issue is severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency, or ADA-SCID. The inherited ailment occurs in between 1 in 200,000 and 1 in 1 million births. That means that four to 20 cases will occur in the U.S. on average every year.

Its victims have nonfunctional immune systems, leaving them vulnerable to a host of infections and requiring them to be sequestered from outside contact — hence the name “bubble baby syndrome.”

Until now, the most effective treatment has involved bone marrow stem cell transplants from a matched donor such as a family member. That didn’t work in Evangelina’s case; not even her fraternal twin sister was a match.

Luckily, Evangelina’s parents were referred to Kohn, who was launching a test of his stem cell-based therapy. Kohn’s discovery was, and still remains, perhaps the most advanced cure of any disease developed with CIRM funding.

Evangelina became the poster child for the potential of CIRM research. As a vivacious 4-year-old, she was featured on the cover of CIRM’s 2016 annual report astride a hobby horse and clad in a pink sweatshirt bearing a lightning bolt, under the legend “CURED.”

Kohn partnered with Orchard Therapeutics to pursue further clinical trials. He was listed as a scientific co-founder upon the company’s launch in 2015, but he says he has no role or authority over its corporate decisions. Indeed, he says he was “gobsmacked” to hear of its decision to shelve the upcoming trial, which he learned from a press release the company issued last May. Since then, he says, he has been “trying to push them to move ahead.”

Kohn and Orchard collected grants from CIRM and other public institutions, including the National Institutes of Health and British medical foundations, and recruited 50 patients for a clinical trial to follow the trial that had included Evangeline. Orchard received an exclusive license to develop the treatment, which it designates internally as OTL-101.

Orchard went public in 2018, ran as high as $20.25 a share in 2019, and has since traded in a range of about $5 to $8. (Its stock closed Tuesday at $5.23.) Like most biotech startups, Orchard has never turned a profit. It lost more than $353 million in 2019 and 2020 and the first quarter of this year on revenues of a negligible $5 million.

The new clinical trial was spectacularly successful. The success rate from donated stem cells was as low as 65%; under Kohn’s therapy, it was 100% — that is, all the trial subjects were living trouble-free lives three years after the initial treatment. The immune systems were restored for 48 of the 50 patients, as Kohn and his colleagues reported in a paper published May 11 in the New England Journal of Medicine, which generated self-congratulatory press releases from both Orchard and CIRM.

Meanwhile, as reported by David Jensen, whose indispensable California Stem Cell Report first unearthed the Orchard case, Orchard received FDA designation for OTL-101 as an orphan drug, a breakthrough therapy and a rare pediatric disease designation. Those would allow for expedited review by the FDA.

First, however, Orchard is required to stage a clinical trial to validate its manufacturing process for the therapy. The FDA would examine the results to determine whether to issue a biologics license to Orchard allowing it to start marketing OTL-101 to the public. That trial would have involved only three patients but would take more than a year to complete.

Last May, however, Orchard changed course. It unveiled a “new strategic plan” in which its research spending would be “more tightly prioritized around high need, high value” products. Deep in the announcement, Orchard said it would “reduce investment in ADA-SCID.” That meant that the manufacturing trial would be shelved.

These and other steps would allow Orchard to reduce its workforce by 25% and produce savings of $125 million through the end of this year, the company said. In an October filing with the government’s database of clinical trials, Orchard said only that recruitment of subjects for the new trial was “on hold for business reasons.” The company told me by email that the trial was suspended for reasons “not related to safety or efficacy.”

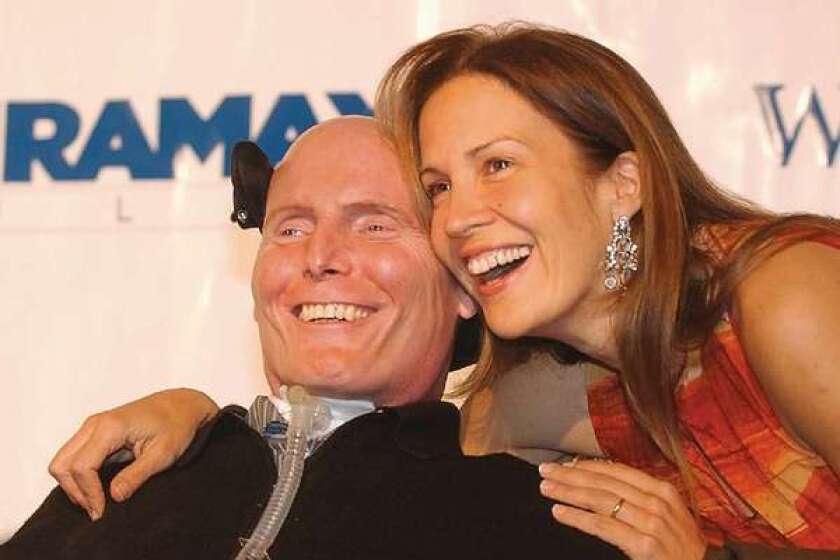

Evangelina Padilla Vaccaro of Corona is the new face of stem cell science in California.

Here’s what that means: Until Orchard performs the next clinical trial, disease victims can’t access the ADA-SCID treatment to which Orchard holds exclusive rights. Orchard hasn’t said when or if it will go through with the trial — it says only that the suspension is “for the time being” — but it has made clear that developing the ADA-SCID cure is a low priority.

Indeed, in its latest quarterly financial disclosure, it listed the expense associated with restarting the ADA-SCID trial among the “risk factors” investors should consider.

Orchard also says it’s beginning to explore the possibility of giving access to families prior to FDA approval. But that will take time and there’s no guarantee it will happen.

CIRM, it should be noted, is not entirely powerless in this case. The institute has “march-in rights” allowing it to take back a license under what it says are “certain criteria and circumstances.” A spokesman told me by email that “CIRM reserves the right to exercise such march-in rights,” but wouldn’t say what the conditions are.

Normally, however, funding institutions invoke them against licensees that have shown no inclination to push a research-and-development project along. There are no signs that CIRM has raised the issue with Orchard, as it should have the moment Orchard placed OTL-101 on the back burner.

The institute says only that it is “committed to its mission of doing everything we can to help patients in need and so we are working with all of our stakeholders in moving this project forward.”

“The trial should be continued in some way even if not directly by Orchard, which should put in resources to try to make that transition happen,” says Paul Knoepfler, a prominent stem cell researcher at UC Davis.

Meanwhile, dozens of families are left in limbo, with time ticking away.

“What’s the ethical responsibility of Orchard to treat the children who are waiting?” Padilla-Vaccaro asks. “I don’t think a project like this should sit idle.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.