Column: Strikes and strike threats — what’s behind the new worker militancy and why it’s a good thing

- Share via

After decades of abject somnolence, American labor seems to be stirring.

Last week, 10,000 workers at 14 John Deere assembly plants walked off the job, the first strike at Deere in 35 years. And that was after rejecting a contract that had been negotiated by the United Auto Workers with a 5% raise in its first year.

There’s more. Some 1,400 workers at Kellogg’s four Midwestern plants went on strike Oct. 5 after failing to reach a contract in a year of bargaining over such issues as reductions in healthcare and retirement benefits.

Workers are trying to acquire the knack again of acting collectively.

— Labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan

In Buffalo, N.Y., 2,000 nurses, technologists and other service workers walked off the job at Catholic Health Mercy Hospital after the hospital and their union, the Communications Workers of America, failed to reach an agreement over what workers say are inadequate pandemic safety measures and sick leave; the union says the employer has moved in a positive direction on those issues but not on pay and staffing minimums.

Healthcare appears to be at an inflection point. More than 350 staff members at a Sutter Health hospital in the Northern California town of Antioch staged a one-week walkout earlier this month.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

And on Oct. 11, nearly 21,000 nurses, pharmacists, midwives, physical therapists and others represented by United Nurses Assns. of California/Union of Health Care Professionals, or UNAC/UHCP at Kaiser Permanente facilities in Southern California voted overwhelmingly — 96% — to approve a strike, the union says.

Their issues include Kaiser’s plan to impose a wage scale lower by as much as 39% for new employees in those job classifications beginning in 2023.

Such “two-tiered” wage systems have been among employers’ most popular tools for cutting payrolls. But they tend to destroy solidarity on the workplace floor, which is one feature that employers like about them.

Whether the outbreak of worker activism will have legs is hard to gauge just now. In part, that’s because the tight late-pandemic labor market has shifted the balance of power in labor relations toward workers more than at any time since World War II, another era of worker shortages. How long that situation will last is anyone’s guess.

Unemployment benefits didn’t keep Americans from returning to the workforce, since they’re still not clamoring for lousy jobs even after those payments have expired.

But other factors are at work.

The pandemic brought home to workers that “we have really degraded work and job quality for four decades,” says Lawrence Mishel, the former president of the labor-oriented Economic Policy institute. “Being mistreated during the pandemic by employers not providing extra compensation and appropriate safety measures got people’s attention.”

Strikes aren’t the only manifestation of workers’ newfound leverage.

“The labor market is so tight that these issues resolve themselves without strikes,” says Thomas Geoghegan, a Chicago labor lawyer and author of the classic 1991 book “Which Side Are You On? Trying to Be For Labor When It’s Flat on Its Back.” “A number of strikes were headed off not because the unions gave up but because the employers gave up.”

The most notable example of that is the resolution this weekend of the threatened strike by more than 60,000 film and television crew members represented by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, or IATSE.

Facing the prospect of a walkout by sound technicians, carpenters, makeup artists, set decorators, costume designers and other production workers in what would have been the first strike in the union’s 128-year history, producers settled.

The newly negotiated contract provides for 3% annual wage hikes, improvements in pay and conditions on streaming productions, observance of the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, and a rest period of 10 hours between daily shoots and 54 hours on weekends. The deal is still subject to ratification by the members, not all of whom are certain that the union got as much as it could have.

Another factor contributing to workers’ leverage is the Biden administration and its distinctly pro-labor policies.

A California judge got it right: Prop. 22, California’s gig economy law, outrageously trampled on employee rights.

“For many decades no president ever took seriously putting his thumb on the scale for workers,” Mishel told me. “Some were definitely trying to undercut workers” — chiefly Republican presidents. Democrats for the most part didn’t undercut workers, but they didn’t do a lot for workers. Biden is a totally different cat.”

In February, for instance, Biden issued a video message supporting a unionization drive by workers at Amazon’s Bessemer, Ala., warehouse. In the extraordinary statement, Biden specifically took aim at Amazon’s tactics to fight the union drive, underscoring the right to organize a union “without intimidation or threats by employers.”

Biden has taken an all-of-government approach to labor rights. He has installed pro-worker leadership at the National Labor Relations Board and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. His Build Back Better bill, which we’ve been writing about in recent days, includes several provisions aimed at redressing the imbalance between employer and employee rights that developed over the last four decades, or more.

The bill would allow the NLRB for the first time to issue fines for violations of the National Labor Relations Act. Companies found guilty of unfair labor practices, such as firing or harassing workers involved in union organizing, could be fined up to $50,000 per violation — $100,000 per violation by repeat offenders.

That’s a major strengthening of the law. Currently, the NLRB has no authority to impose monetary penalties; it can only seek injunctions and order back pay and reinstatement of a worker improperly fired.

In extreme cases, an employer can also be ordered to post a notice in the workplace for 60 days notifying the workforce that it’s been found in violation of the law. In technical jargon, that’s known as a “Big Whoop.”

The Build Back Better bill would also allow the NLRB to judge whether a company’s directors or officers should be personally liable for unfair labor practices.

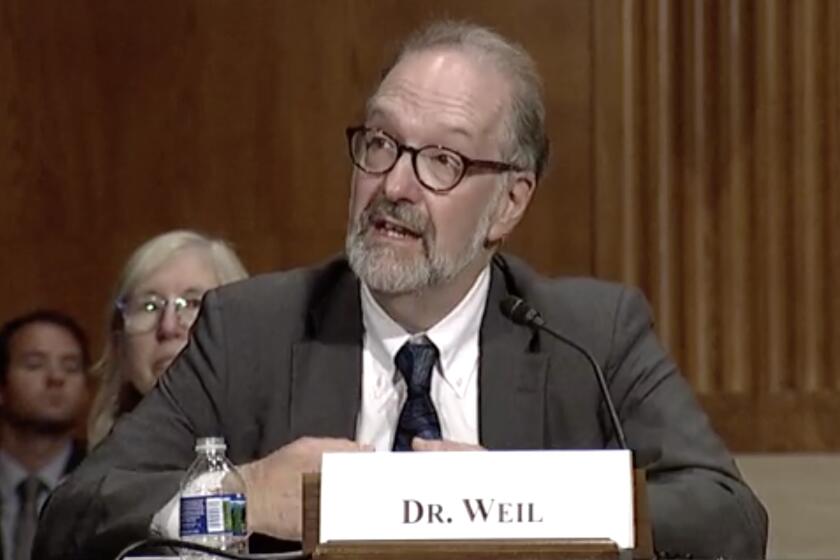

Business and the GOP think the Labor Department should be anti-labor. To them, that makes Biden nominee David Weil a dangerous radical.

The bill would also give the NLRB the authority to fine employers for hiring permanent strikebreakers, holding so-called captive meetings at which they pour anti-union bile into workers’ ears, or reclassifying employees as independent contractors to deny them the right to organize.

All that would put more teeth into U.S. labor law than it’s had since passage of the stupendously anti-union Taft-Hartley Act, which was enacted over a veto by President Harry S Truman in 1947.

Biden is a strong supporter of the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which passed the Democratic House in March with one Democrat in opposition and five Republicans in support.

The PRO Act would be the most important law protecting worker rights since the original National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Among other virtues, it would overturn numerous provisions of Taft-Hartley.

Among the PRO Act’s co-sponsors is Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W. Va.), who has been getting castigated recently for his opposition to the Build Back Better bill. In this particular, however, he’s on the side of the angels.

The Deere strike may be the best example just now of how fed up unionized workers have become with their leadership. The UAW allowed the Big Three automakers to impose two-tiered wage rates in 2007, a supine concession that quickly spread to other UAW contracts, including Deere.

The most anti-union law in the U.S. is the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. It should be repealed.

The contract the union negotiated with Deere would begin the process of restoring benefits that have been consistently whittled away over the years, including the two-tier wage rates, but only modestly — the 5% raise in the contract’s first year would amount to $1 per hour on the $20 hourly base pay, as Jonah Furman of Labor Notes reported.

Given that Deere is projecting record profits this year of more than $5.7 billion, the rank and file plainly thought that wasn’t enough. The compensation of John C. May, the company’s chairman and CEO, more than doubled last year to $15.6 million from $6 million the year before. Its 10 outside directors, whose responsibilities include attending board and committee meetings every few weeks, were paid an average of more than $297,000 in 2020.

The most important issue facing the American labor movement is how to build on workers’ leverage in the current tight labor market to secure long-lasting structural change in labor-management relations.

Geoghegan sees some glimmers of hope. Among them are potential changes in management at the Teamsters and United Auto Workers unions.

An insurgent slate headed by Sean O’Brien and Fred Zuckerman is running in a leadership election at the Teamsters, with a promise to “rebuild the Teamsters as a militant, fighting union from bottom to top.” Mail-in ballots are due by Nov. 5.

In November, UAW members will vote on a referendum to change the union’s method of electing leadership to direct election, “one member, one vote.” The goal is to take the process out of the hands of a moribund “administration caucus” that has controlled the appointment of top executives for decades.

Critics say that system has cemented a corrupt, listless leadership in place. The referendum is the result of a consent decree the UAW leadership reached with the Department of Justice on Jan. 29.

“Those things are not strikes, exactly,” Geoghegan says, “but they would be changes in the temperament of two very important unions. Workers are trying to acquire the knack again of acting collectively.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.