Column: A labor regulator protecting workers? To Big Business, that’s ‘unfit’

- Share via

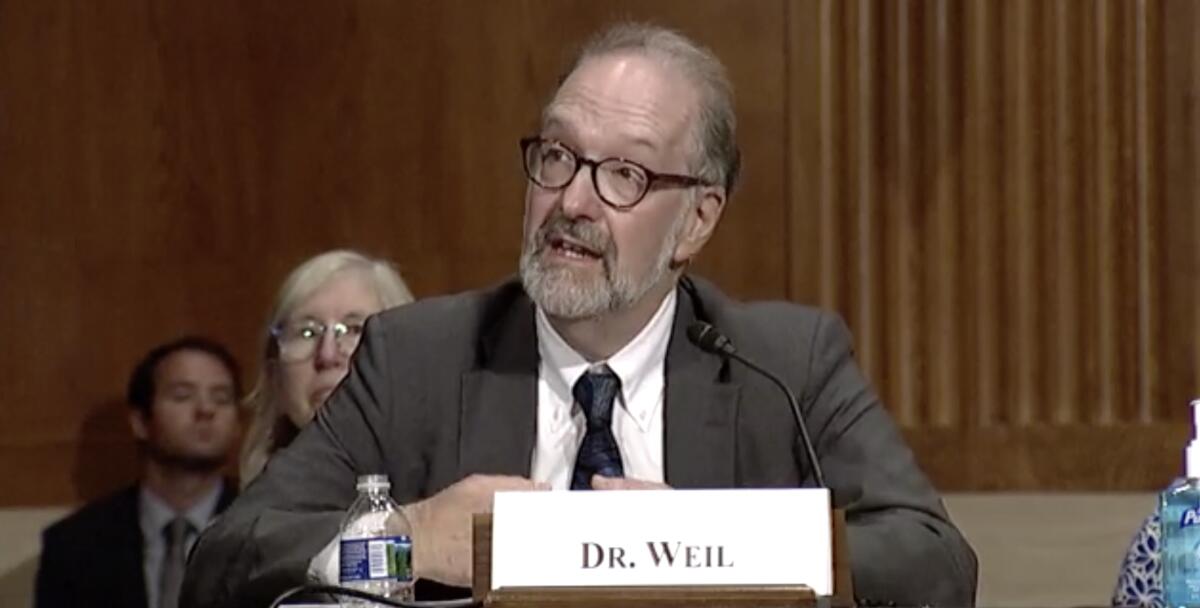

David Weil doesn’t come across as a bomb-throwing leftist extremist, not this soft-spoken academic with tortoiseshell glasses, a receding hairline and his unfailingly polite replies to accusatory questions from some members of a Senate committee considering his nomination to a high Department of Labor post.

Business lobbies say they aren’t fooled by such superficialities. At Brandeis University, where he is dean of the Heller School of Social Policy and Management, Weil has “pushed critical race theory and Marxist thought on students,” according to Heritage Action, an offshoot of the right-wing Heritage Foundation.

A coalition of 14 industry groups, including the International Franchise Assn. and the National Restaurant Assn., sent a letter to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions calling Weil “unfit” to head the department’s powerful Wage and Hour division.

Weil is a major advocate of unionization.

— Pro-business Competitive Enterprise Institute, thinking it’s attacking a Labor Dept. nominee

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce sent a separate objection. In his previous stint as the division’s director during the Obama administration, the chamber groused, “Dr. Weil took positions on critical questions” such as “whether an employee would be exempt from overtime, finding joint employment relationships, and whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor.”

The chamber’s complaint isn’t that Weil took positions on those issues, but that his positions uniformly favored workers.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The pro-management Competitive Enterprise Institute put its objections most succinctly. “Weil,” it said, “is a major advocate of unionization.”

It shouldn’t be surprising, one supposes, for business lobbies to object to placing a pro-labor individual high up in the Department. of Labor. They became accustomed to getting their way during the Trump administration, which worked assiduously to turn the agency into the Department of Employer Rights.

Trump did so by rescinding many of the regulations that had been put in place by Weil himself. The implicit idea, hailed by the business community, was that the federal government didn’t have enough agencies favoring business, so why not add the Labor Department to the list?

Now Trump’s actions are being overturned by the Biden administration, which is developing an extensive portfolio of pro-worker policies. Reinstalling Weil at Wage and Hour is part of that strategy.

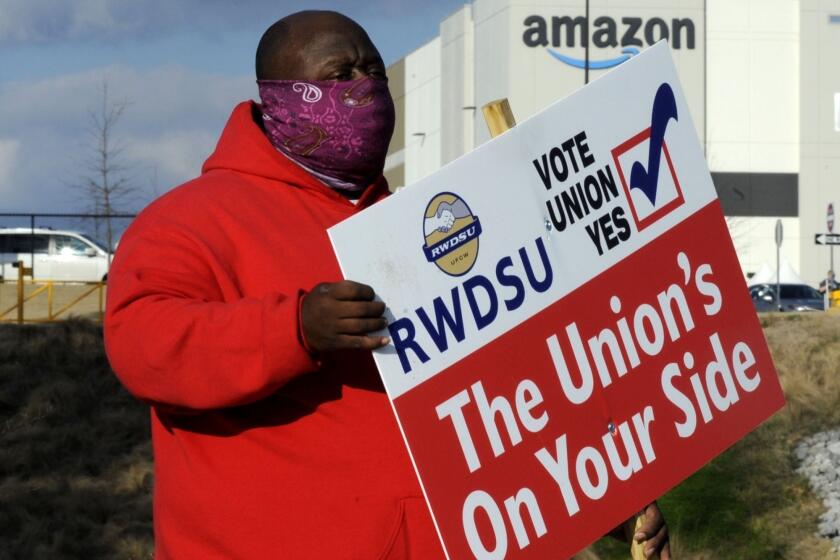

So is Biden’s support for the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, or PRO Act, a sweeping measure that would ban a whole sheaf of actions used by employers to interfere with union organizing.

These include holding meetings to dispense anti-union propaganda, which workers are required to attend; firing workers engaged in union organizing; and misclassifying employees as independent contractors to deprive them of unionization rights.

Sen. Joe Manchin endorses the pro-labor PRO Act, but it still faces an uphill climb in the Senate.

The PRO Act also would overturn the right-to-work laws in force in 28 states. These laws require unions to represent all employees in a unionized workplace without requiring them to pay union dues, a cynical stratagem aimed at depriving unions of financial resources.

Weil appeared at his confirmation hearing alongside Gwynne A. Wilcox and David Prouty, two labor lawyers nominated for seats on the National Labor Relations Board. They all faced determined grilling by the committee’s GOP members, but Weil was the focus. Committee votes on the nominations could happen as soon as Wednesday.

The fear most often voiced by the business lobby is that Weil would implement many of the PRO Act’s provisions through regulatory action.

“Weil has embraced the harmful PRO Act, and IFA is concerned he will attempt to bypass Congress and enact its most damaging components through regulatory fiat,” Michael Layman, a spokesman for the International Franchise Assn., told the Hill.

A common thread in the anti-Weil critique is that he’s an unelected bureaucrat who never met a payroll. This is a familiar rubric for attacks on government officials doing the jobs they’ve been appointed to do.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis invoked it in a recent fundraising appeal, calling Dr. Anthony Fauci “an unelected career government bureaucrat” trying to deprive Americans of their freedom by advocating mask wearing and social distancing to beat the pandemic.

Thus Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.), ranking member of the Senate committee considering Weil’s nomination, started off by stating, “Before Congress, I worked for a living.” It’s true that before coming to Washington, Burr spent 17 years as a salesman. But he’s been in Congress and the Senate for 25 years since then.

Weil neatly disarmed this fatuous attempt to portray him as an academic with his head in the clouds. At the Department of Labor, he noted, he ran an agency division with a $235-million budget and 2,000 employees, and at Brandeis he runs an institution with a $32-million budget and 200 full-time employees. “I think that characterization of my experience is a little off,” he said.

Proposition 22 is a revolutionary step in the influence of tech-based businesses in our daily lives in general and the lives of workers in particular.

Let’s take a closer look at Weil’s approach to worker rights.

At the Wage and Hour division, he was responsible for a regulation that doubled the threshold of eligibility for overtime pay to $47,476 in earnings from $23,660 a year, adding about 4 million workers to the ranks of those entitled to time-and-a-half pay for work in excess of 40 hours a week. Trump rolled that back to $35,568, cutting about 2.8 million workers out of the overtime ranks.

“Employers are concerned that this salary threshold may be increased under Dr. Weil,” the Chamber of Commerce says.

Weil also moved strongly against the use of subcontractors to conceal employer-employee relationships — thus absolving major employers of responsibility for workers.

As he observed in a paper last year, this variety of outsourcing concentrates labor costs among ever smaller and less profitable subcontractors, so that “incentives to cut corners rise, leading to violations of our fundamental labor and employment standards.”

The answer was an effort during the Obama years to solidify “joint employer” standards, requiring the ultimate employer to share costs and responsibility for the workers.

Weil kept a sharp eye out for the subterfuges used by businesses to claim they weren’t really “employers” of their workers, such as by asserting that the workers were merely “independent contractors.” That claim absolved them of paying employee benefits, such as minimum wage, overtime, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation.

To see this scam in action, just look at Proposition 22, the 2020 California ballot measure that Uber and its fellow gig employers drafted. The companies spent more than $200 million, an unprecedented sum, to pass the initiative, which relegated their drivers and delivery workers to permanent indentured status in the name of “freedom” and “flexibility.”

Once it passed, the companies started systematically taking away the benefits the workers thought they would gain from Proposition 22.

Trump’s evisceration of labor protections will continue under Labor Department nominee Scalia

Weil gained the reputation of a foe of Uber, Lyft and other gig companies trying to keep their worker costs down. It was well and properly deserved. In an op-ed for The Times during the run-up to the Proposition 22 campaign, he acknowledged that some employer-worker relationships might fall into a gray area making it hard to determine if the workers were contractors or employees.

“Uber and Lyft are not among those close, gray-area cases,” he wrote. “Their status as employers is really quite clear.”

The business lobby typically describes its pushback against employer classification as “protecting the right to be a gig worker.” This transparent dodge conveniently overlooks the imbalance of power in the employer-worker relationship, sharply tilted as it is in favor of the former.

Such talk about the rights of the worker in this context was memorably deconstructed by Harold Ickes, a close aide to Franklin D. Roosevelt (and a Republican in the days when one could be a Republican and a liberal). Ickes described a 1936 Supreme Court decision overturning a New York minimum wage law in a case brought by laundresses as upholding “the sacred right … of an immature child or a helpless woman to drive a bargain with a great corporation.”

Weil acted to strengthen the rules on when a worker must be considered an employee. The chamber complained that this caused “confusion and uncertainty” among employers trying to determine how to classify their workers. But that’s a joke: Notwithstanding the limited gray areas mentioned by Weil, businesses almost always know full well when their workers deserve employee benefits. They just don’t want to pay them.

The effort of redirecting all the government’s labor agencies — the Department of Labor and the National Labor Relations Board are the most prominent, but not the only such agencies — is a work in progress.

But Weil’s confirmation, along with those of Wilcox and Prouty, will move the process smartly along. The claims of the business lobby that they’re pro-labor is the best endorsement imaginable.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.