Column: Mark Zuckerberg just made the case for breaking up Facebook

- Share via

The problem with giant corporations sometimes isn’t simply that they’re too big, but that their sense of their social impact is too small.

Exhibit A: Facebook.

The giant social media firm’s co-founder and chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, on Tuesday convened a 90-minute video town hall for its employees.

We need to hold Facebook accountable and break it up so there’s real competition – and our democracy isn’t held hostage to their desire to make money.

— Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.

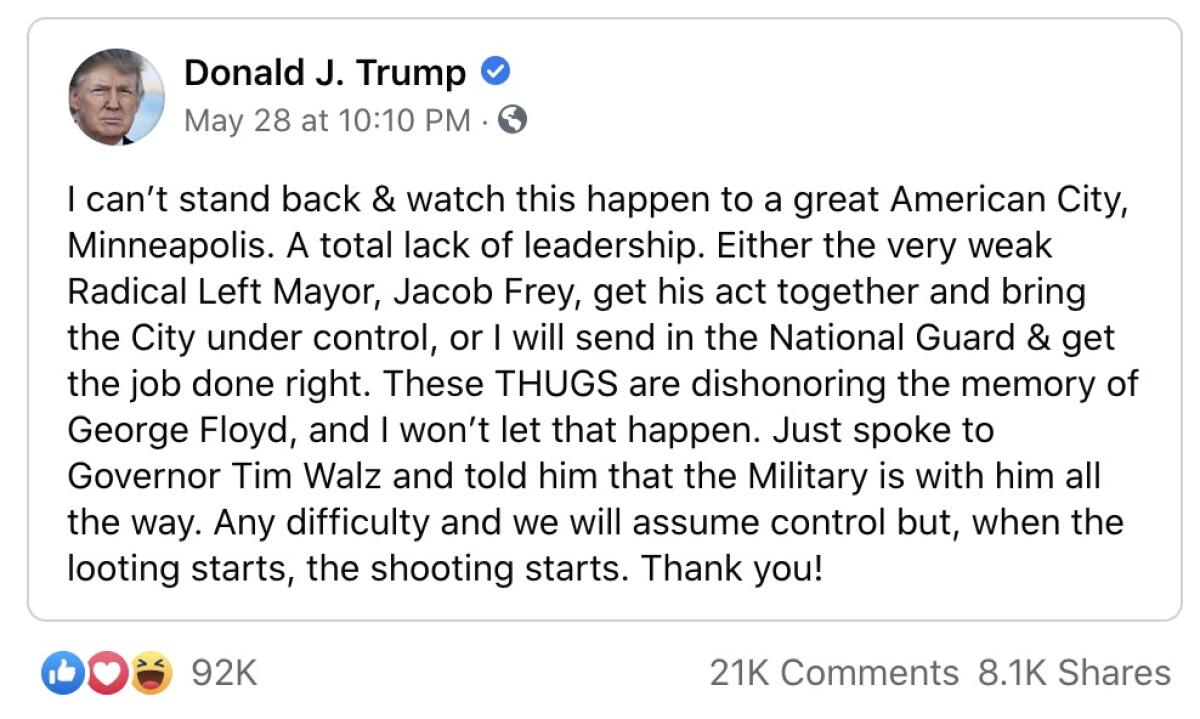

His goal chiefly was to address internal angst about his decision not to take down, flag or otherwise moderate recent postings by President Trump that appeared to threaten the use of official violence against protesters of police racism and brutality.

Trump cited a line attributed to Miami Police Chief Walter Headley in 1967 during the civil rights movement, plainly alluding to a violent police response to disorder: “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

If employees or any other observers of Facebook history expected Zuckerberg to defend his action by wrapping himself in the principle of freedom of expression, offering a convoluted explanation of how he arrived at his decision, and conceding that he might have stumbled a bit in the process but would do better in the future, they were not disappointed.

Facebook’s investors weren’t fazed by its $5-billion fine. So what would shake them?

“I do think that expression and voice is ... a thing that routinely needs to be stood up for,” Zuckerberg said.

He walked step-by-step through his cognitive journey toward leaving the posts untouched. And he said, “I think we could have done a little bit better. ... This is an area where we need to think through” policies and practices.

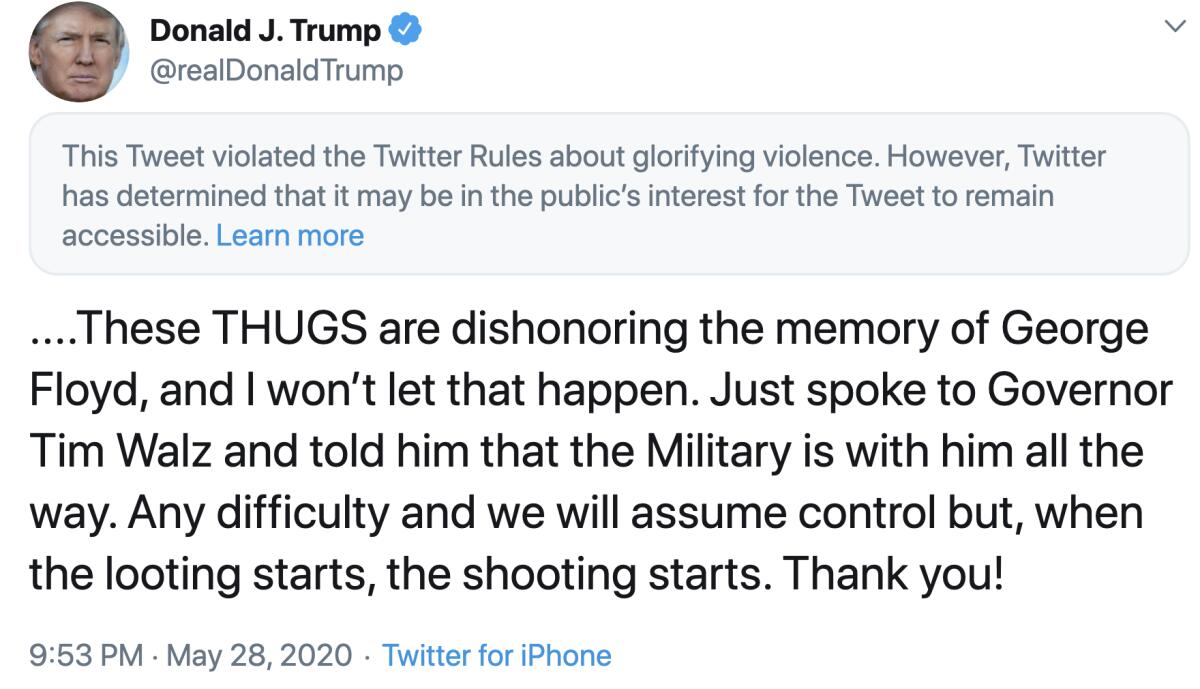

The much smaller Twitter dealt with Trump’s tweet on the protests, which was largely identical to his Facebook posts, by obscuring it with a tag stating that it violated Twitter’s “rules against glorifying violence.” The tag required users to click a second time to view the tweet.

Zuckerberg left the impression that he had weighed Trump’s message in a manner almost calculated not to interfere with Trump’s access to Facebook’s tens of millions of users. Although he mentioned conferring with a raft of internal advisors — only one of whom, he acknowledged, was black — it was clear that the decision was his alone.

He apparently did not reach out to anyone outside the company, though he said Trump called him. A meeting he held with several civil rights leaders protesting the decision to leave up the Trump posts ended in disaster, when the leaders issued a statement calling Zuckerberg’s explanation “incomprehensible.”

They added, “He did not demonstrate understanding of historic or modern-day voter suppression and he refuses to acknowledge how Facebook is facilitating Trump’s call for violence against protesters.”

That’s consistent with Zuckerberg’s position as the dominant, even despotic ruler of Facebook, cemented in place by his control of nearly 60% of Facebook’s shareholder votes.

And that points to a larger issue raised most directly by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) last year during her campaign for the Democratic nomination for president: Isn’t it time to break up Facebook into smaller pieces?

The answer is yes. To explain why, let’s examine some core principles.

Suspicion of concentrated corporate power is a thread running through much of American history. Adolf Berle, a member of Franklin Roosevelt’s Brain Trust, put it succinctly as a response to Herbert Hoover’s praise of “individualism.”

Trump is only pretending to attack Twitter

Berle wrote during the 1932 campaign: “Whatever the economic system does permit, it is not individualism. When nearly 70% of American industry is concentrated in the hands of 600 corporations, the individual man or woman has, in cold statistics, less than no chance at all.”

The menace pondered by Berle, however, was nothing compared to that posed by web giants such as Facebook, Amazon and Google, the three main targets of Warren’s breakup proposal.

The reach of these firms goes beyond the selling of merchandise and domination of capital. Aided by the “network effect,” through which they become ever more important to users as their enrollment grows, these companies have the ability to control and exploit for financial purposes the flow of information.

For all that Zuckerberg talks about Facebook’s giving “people the power to build community and bringing the world closer together,” as he stated during his employee address, the truth is that power flows chiefly toward Facebook, not out to the community.

“Networked technology is often more prone to concentrate power than it is to diffuse it,” Frank Pasquale, an information law expert at the University of Maryland, wrote in 2016. A company with a massive user base — Facebook’s global count of monthly active users has reached 2.6 billon — has the ability to become “a ‘kingmaker’ in both content and commerce,” he wrote.

Back at the time of Facebook’s initial public offering in 2012, I advised its new stockholders: “Congratulations.

As we’ve reported, existing law allows information platforms such as Facebook nearly complete latitude to decide whether and how to oversee content posted independently by users.

Typically, big platforms have taken a hands-off approach except when user-generated content crosses well over the lines of social acceptability, such as overt racism, anti-Semitism, hate speech, or incitement to violence.

President Trump’s posts and tweets present unprecedented difficulties, largely because presidential pronouncements have been regarded as official communications -- generally carefully fashioned to avoid giving offense.

Trump’s tweets and posts have taken a 180-degree turn from those traditions. In the remarkable broadside he leveled at Trump Wednesday, former Defense Secretary James Mattis wrote that “Trump is the first president in my lifetime who does not try to unite the American people — does not even pretend to try. Instead, he tries to divide us.”

That’s the context for Zuckerberg’s comments. He explained that Trump’s posts hinting at a violent response to could be interpreted in any of three ways: As “a discussion of state use of force, which is something we allow”; as “a prediction of violence in the future,” also allowed; or as “incitement of violence,” which is forbidden to all users.

Zuckerberg called Trump’s repetition of the Headley threat a reference “clearly to aggressive policing,” but asserted that it has “no history of being read as a dog whistle for vigilante supporters to take justice into their own hands.” In the end, Zuckerberg said, he arrived at the conclusion that Trump’s posts were “troubling” but not violative of Facebook policies.

In 2012, Tristan Harris made a presentation to his bosses at Google arguing that “we had a moral responsibility to create an attention economy that doesn’t weaken people’s relationships or distract people to death.”

His explanation failed to quell the internal objections.

At least two Facebook executives have resigned over the matter. Scores of employees, most of whom are working at home during the coronavirus pandemic, staged a virtual walkout on June 1 by posting that they were away from work.

Several dozen former employees observed in an open letter that Facebook regularly deletes posts by users that are as menacing and provocative as Trump’s.

Current Facebook executives, the letter said, “have decided that elected officials should be held to a lower standard than those they govern.”

Zuckerberg’s explanation may not have carried much weight because it echoes the company’s responses to previous controversies. Cited for repeated violations of user privacy, the company attributed the violations to mishaps and Zuckerberg pledged to do better.

Ultimately, the Federal Trade Commission slapped the company with a record $5-billion fine last year for violating an earlier FTC privacy settlement. But as steep as that fine was, it amounted only to about what the company collects in revenue in a single month.

Among the privacy breaches that Facebook allowed to happen was one in which the personal information of as many as 87 million people ended up shared with the data collection firm Cambridge Analytica, which then allegedly used it on behalf of the presidential campaign of Trump and the pro-Brexit campaign in Britain.

That leaves us with the difficult question of how Facebook’s influence over public discourse — that is, Zuckerberg’s influence — can be restrained.

Facebook has responded to increasing concerns over its poor moderation of noxious material or political disinformation by announcing an independent “oversight board” to supervise content moderation policies and rule on decisions to take content down. But the board won’t be fully in place in time for the upcoming presidential campaign — the first 20 of its 40 members were only named last month.

How much independent authority the board will have remains an open question. Even Facebook acknowledges that the 40 law professors and other luminaries serving on its board part time will be hard pressed to rule on even a tiny fraction of the thousands of cases in which content decisions are needed. It’s a fair bet that, in the end, Zuckerberg will still be setting policy.

What’s left?

Warren’s proposal would unwind mergers in which social media platforms have been permitted to own participants on those platforms. Facebook, for example, would have to split off WhatsApp and Instagram. Her intent is to clip the big companies’ financial wings to reduce their economic incentives to trample over competition and infringe users’ rights.

“We need to hold Facebook accountable and break it up so there’s real competition — and our democracy isn’t held hostage to their desire to make money,” Warren told me by email. “That’s how we will fix a corrupt system that lets Facebook stomp on our privacy, engage in illegal anti-competitive practices, and bend over backward to allow politicians like President Trump lie on its platform for profit.”

Among the few options that fall short of government regulation of speech on social media — almost certainly a legislative non-starter — is for employees and users to apply pressure. A “delete Facebook” movement, akin to the “delete Uber” drive among users protesting the ride-share company’s profiteering practices, is in barely a fetal stage. But it could grow if the company’s solicitude toward Trump generates public discontent. The outbreak of resignations by executives is also modest, thus far.

Facebook’s inaction on Trump’s latest posts has produced the most significant pushback by insiders in its history. A bit more of that, along with the prospect that he could be leading a smaller company in the future, might lead Zuckerberg to think even harder about Facebook’s responsibilities not merely to its bottom line, but its social surroundings. Not much else seems likely to move him.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.