Column: If a $5-billion fine won’t shake Facebook, what can bring it to heel?

- Share via

Let’s talk about big numbers. Five billion dollars is a big number. If you spent it at the rate of $20 a second, it would take you about seven years and 11 months to spend it all. If you salted away $100 a day, it would take you nearly 137,000 years to have $5 billion (not counting interest earned).

Five billion dollars also can be a small number. If you’re Facebook, for example, and you collect that sum in revenue in an average month and more than four times as much in profit in a single year.

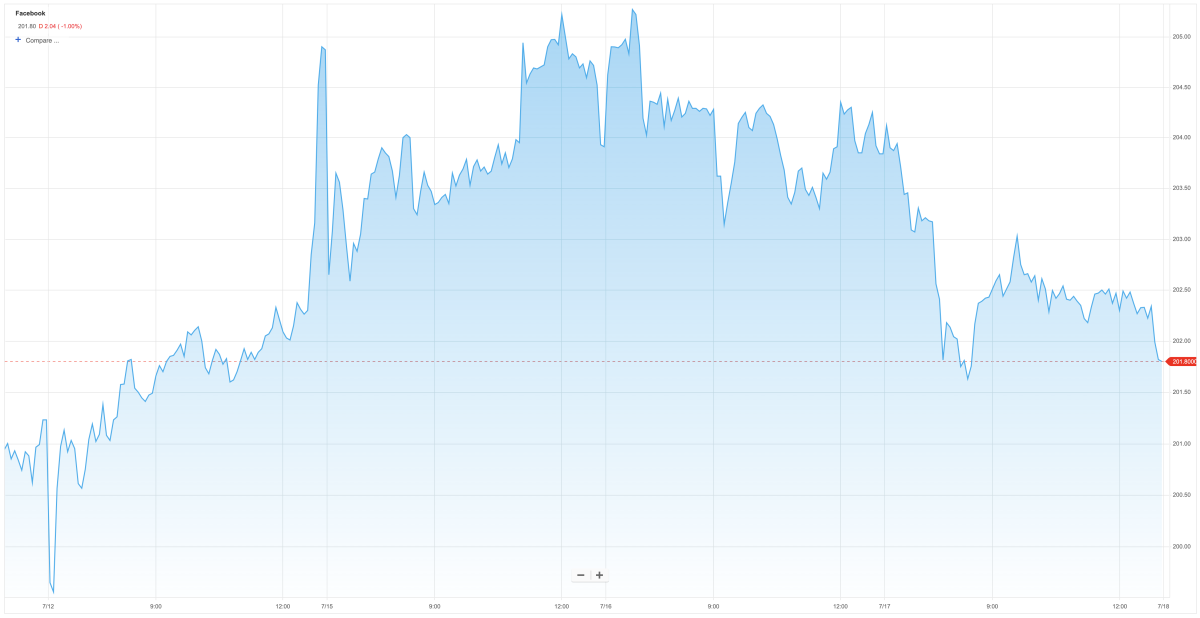

Those are telling metrics. They help to explain what happened on July 12, minutes after a report surfaced that the Federal Trade Commission had voted to hit the company with a record $5-billion fine for violating the terms of a 2011 FTC settlement over privacy practices.

A large fine is necessary, but not sufficient. A lot more needs to be done.

— Marc Rotenberg, Electronic Privacy Information Center

Facebook’s stock price spiked upward, to about $205.30, gaining about $3 per share in the blink of an eye. The surge temporarily added about $7.5 billion to Facebook’s market value, which most people might consider a win for the company. It gave up most of that gain before the start of the following trading day, but since then, with the $5-billion fine still hanging over the company, the shares have moved back toward the 52-week high of $217.50 they had reached on July 25, 2018.

Why would an unprecedented government penalty prompt a company’s shares to move higher? There are two factors. One is that Facebook had been telegraphing for months that it expected a fine in the range of $3 billion to $5 billion, and already had accrued a reserve of $3 billion against that possibility. In other words, a stiff fine already was baked into the stock price.

Good corporations know that the secret to success is to focus on your best quality and use it to serve your customers.

The bigger reason, however, may be that investors concluded that the fine is basically the extent of the punishment being meted out to Facebook by the FTC for violations related to the breach of its users’ privacy through the data mining firm Cambridge Analytica. All the details of the agency’s action aren’t known — the initial July 12 report in the Wall Street Journal stated only the size of the financial penalty and the vote, which was 3 to 2 along party lines, Republicans in the majority. Facebook’s critics say that if that’s so, then the penalty is a slap on the wrist.

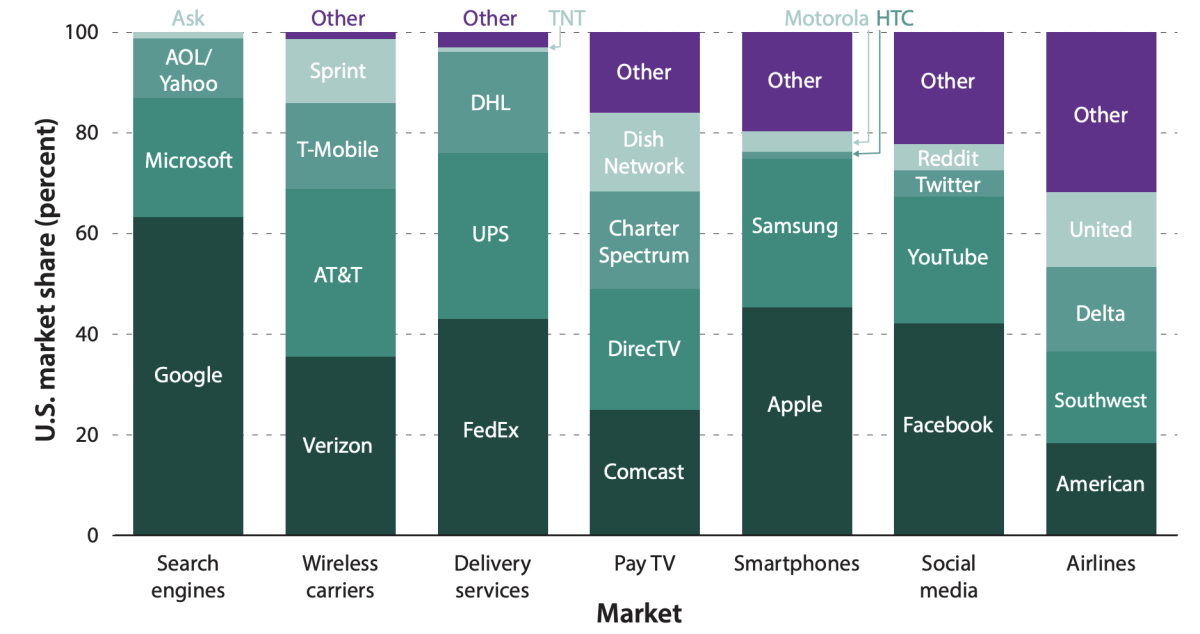

“We’ve said that a large fine is necessary, but not sufficient,” Marc Rotenberg, president of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, or EPIC, told me. “A lot more needs to be done,” chiefly structural changes, including a forced divestment of the social media platforms Instagram and WhatsApp, which were competitors of Facebook until it acquired the first in 2012 for $1 billion and the second in 2014 for $19 billion. Both have become the focus of concerns over how Facebook collects and exploits the private personal information of their users. They’re essential to Facebook’s corporate strategy, which suggests that avoiding a divestment order may have made Facebook more amenable to a 10-figure fine.

Facebook’s relationship with regulators is on everyone’s radar screen right now. The FTC action, which may not be formally made public for weeks, is only one reason. There are also the calls by prominent Democrats, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and other contenders for the presidential nomination, to break up Facebook and such other technology behemoths as Google and Amazon.

In unveiling her plan last March, Warren asserted that the big tech companies wield “too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy.... They’ve bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit, and tilted the playing field against everyone else.”

Judging from the proxy statement issued by Facebook last week in advance of its May 30 annual meeting, the company’s shareholders are starting to get fed up with its leadership by co-founder, Chairman and Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg.

The dominance of Facebook, along with a handful of other big firms, has broad implications for our economy. It may be showing up in what the Brookings Institution found to be an economywide decline in rates of start-ups — especially among high-tech firms since 2000. One explanation is that “increased market concentration is making the environment for start-ups inhospitable,” Brookings said in a June 2018 report. (Officials of all three of the firms, plus Apple, appeared at a hearing before the House Judiciary Committee on Tuesday to defend their size and sweep and to counsel against breaking them up.)

Then there’s Facebook’s latest proposed venture. It’s a bitcoin-like cryptocurrency dubbed Libra. As we’ve reported, Facebook has presented Libra as “a simple global currency and financial infrastructure that empowers billions of people.” But it really looks like a scheme to open a new path to profit and power for Facebook, dressed up as a global boon to billions of unsuspecting people.

Libra got fairly well raked over the coals in congressional hearings on Tuesday and Wednesday. The lawmakers raised the most obvious point, which was why anyone should trust Facebook’s promise that the privacy of Libra account holders would be safeguarded from breaches by, well, Facebook. “Like a toddler who has gotten his hands on a book of matches, Facebook has burned down the house over and over, and called every arson a learning experience,” Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) said at a hearing before the Senate Banking Committee in a fairly typical, if especially evocative, observation. “We would be crazy to give them a chance to ... use powerful tools they don’t understand, like monetary policy, to jeopardize hardworking Americans’ ability to provide for their families.”

In 2012, Tristan Harris made a presentation to his bosses at Google arguing that “we had a moral responsibility to create an attention economy that doesn’t weaken people’s relationships or distract people to death.”

Libra, however, is a speculative venture from which Facebook hopes to make money if it can sneak the idea past domestic and international currency regulators. What’s more at stake in the proceedings before the FTC and in the calls for high-tech breakups are the existing businesses from which it earned more than $22 billion in profit last year.

EPIC’s Rotenberg maintains that what Facebook most wants to avoid is government regulators interfering with its efforts to further integrate apps such as Whatsapp and Instagram into its ecosystem. “They want to know that they can proceed largely without constraint,” he says. “They don’t mind paying a price — and $5 billion is a significant fine — but they don’t want to be obstructed as to their future market plans. That’s why the share price went up” after the FTC vote was leaked.

In his prepared remarks for a July 16 House Judiciary Committee hearing on the market power of tech’s biggest players — Facebook, Google, Amazon and Apple — Facebook spokesman Matt Perault cited his company’s growth from “a dorm room idea to a vibrant and successful American company that now employs almost 40,000 people around the world.” He observed that “Facebook is able to provide nearly all of its consumer services free of charge because we sell advertising.” The spokesmen for Google, Amazon and Apple made analogous claims for their size, payrolls and benefits to consumers.

This was familiar big-corporation humbug, custom-built to obscure the real issues. The question isn’t whether Facebook, Amazon, Google and Apple have vast global reach, make pantsfuls of money and hire thousands of workers; that’s a given for big consumer companies. The real questions are how much more would workers, entrepreneurs and the economy gain if their growth were reined in, and what are the hidden costs in allowing them to continue as they are? How much do Facebook users secretly pay for the loss of their privacy in return for “free” access to its services and apps? How much did American society pay, in the undermining of its democratic process, in return for allowing it to push disinformation, including some originated from Russian sources, to unsuspecting online viewers?

The terms “privacy,” “FTC” and “Cambridge Analytica” didn’t appear in Perault’s prepared statement. But the reason for Facebook’s current regulatory issues is that the company and its chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, have demonstrated time and again that their promises to users and their commitments to government regulators can’t be trusted. They break their promises and commitments all the time.

When they’re caught, they either brush off the implications of their behavior as no big deal, or they cop to their wrongdoing and promise not to do it again, pleading that “We really messed this one up,” “We simply did a bad job with this release,” or “Sometimes we move too fast.” As we observed during a privacy blowup in 2014, this always boils down to the all-purpose plea of “guilty, with an explanation.”

Back at the time of Facebook’s initial public offering in 2012, I advised its new stockholders: “Congratulations.

The FTC’s 2011 settlement involved allegations that Facebook had systematically deceived its users into thinking their privacy settings would keep their personal information from flowing to strangers and that the company falsely told users it wouldn’t share their identities with advertisers without the users’ consent. The settlement required the company to stop misrepresenting its privacy protections and to obtain express consent from users before overriding their privacy settings. Yet as the company acknowledged last year, the personal information of as many as 87 million people ended up shared with the data collection firm Cambridge Analytica, which then allegedly used it on behalf of the presidential campaign of Donald Trump and the pro-Brexit campaign in Britain.

Last year, the FTC said it would open an investigation into the Cambridge Analytica affair. As EPIC noted in a letter to the FTC in January, up to that moment it had never imposed any discipline on Facebook for possible breaches of the 2011 settlement. “We’ve spent the last eight years trying to get the consent order enforced,” said Rotenberg, whose organization brought the initial complaint that ultimately yielded the settlement. Cambridge Analytica was only one example of a data breach. Last year Jan Koum, the founder of WhatsApp, left Facebook reportedly over a disagreement with Facebook’s decision to start accessing the private data of users of WhatsApp, which was built on the promise of absolute data security.

The fact is that even a multibillion-dollar fine won’t dissuade Facebook from pursuing its quest to monetize the private information of its unwitting or uncaring users, and indulging its worst instincts in doing so. Not $5 billion, not $10 billion. Facebook makes too much money for even that much to have a lasting effect, and its potential for making even more is incalculable. The only thing that will work is regulation, up to and including a breakup.

The lawmakers who laced into Facebook during committee hearings Tuesday and Wednesday certainly sounded serious about holding the company to its commitments on user privacy. But one wonders if they would be so outspoken if they really intended to do something about it, and to force the FTC to do its job of regulation. Facebook made $7 million in campaign contributions to federal candidates in 2016 and 2018, and spent $55 million on Washington lobbying just since 2014. Consumers should be nervous; when big companies come to Washington, they almost always get their way.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.