A West Coast union faces bankruptcy. Here’s why unions nationwide are unnerved

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — The union that handles every shipping container that crosses West Coast docks is bracing for bankruptcy. It’s a rare prospect for a bargaining group, and it’s rattling organized labor nationally.

The International Longshore and Warehouse Union traces its roots to a 1934 strike that claimed the lives of two men commemorated by silhouettes marked on a sidewalk in front of Local 10, the organization’s San Francisco chapter. The ILWU’s motto — “An injury to one is an injury to all” — attests to the wariness and solidarity of its 15,000 waterfront members, handsomely compensated blue-collar workers already threatened by port automation.

Few of those workers could have imagined that an obscure feud over two dockside jobs in Portland, Ore., would jeopardize the whole union, whose members line up daily at hiring halls to operate cranes, trucks and machinery in ports from San Diego to Bellingham, Wash. But a $94-million federal jury award Nov. 4 to ICTSI Oregon Inc., a cargo terminal operator, has forced union leaders to warn that a filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection may be ahead.

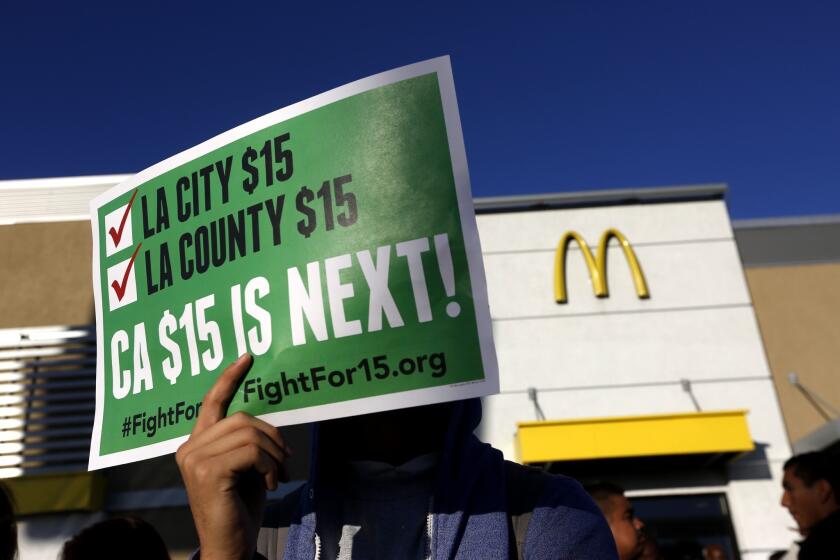

California unions expand, as national labor organizing stagnates

ILWU attorneys will try, during a Feb. 14 hearing in Portland, to persuade U.S. District Judge Michael Simon to reduce the award, which dwarfs the San Francisco-based union’s $20 million in declared assets. But judges tend to be reluctant to overrule juries, doing so only when, in the words of an opinion quoted in a recent ICTSI filing, a decision appears “wrong with the force of a five-week-old, unrefrigerated dead fish.”

If Simon lets the award stand, it could provide a dangerous precedent, said Donald Marcus, president of the International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots, a Maryland-based licensed-mariners’ union. “It’s an attack on the trade union movement and could have very negative repercussions for union workers and labor generally,” he said.

“We won’t recognize labor on the West Coast in the maritime industry if the ILWU is no longer there and at the forefront,” Marcus said. “They set the whole tone and pace of progressive unionism for maritime labor.”

Labor leaders fear that the award could embolden other employers, as organized labor deals with setbacks including the Supreme Court’s 2018 Janus ruling that public employees cannot be forced to pay dues or fees to support their unions. The ILWU’s predicament reminds some labor managers of the pre-1930s era, when judges hit unions with fines and injunctions before Congress passed federal protections.

But in Portland it was a jury of six women and two men, not a judge, who ruled for ICTSI Oregon and set the award amount. And ILWU leaders had displayed unusual defiance, repeatedly threatening to harm the company’s business. The union risked its fortunes at a time when its prosperity seemed assured, riding on booming trade at West Coast ports.

The ILWU has parlayed its niche, handling ocean cargo worth trillions of dollars, to land lucrative labor contracts with the Pacific Maritime Assn., an employers’ group of shipping lines and terminal operators. Union dockworkers make an average of $171,000 a year plus free healthcare.

Clerks average $194,000, and foremen, or “walking bosses,” $282,000. Their paychecks dwarf those of many white-collar managers in the global economy, let alone other transportation workers, including members of the East Coast longshore union.

As contract renewals approach, negotiations sometimes stall, leading to massive freight backups at the West Coast’s 29 container ports. For leverage, the union has developed “hard-timing” and “working to rule” into an art form, gumming up the works through slowdowns and literal interpretation of regulations.

Robots are coming to the massive ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, replacing dockworker jobs. But truckers are delighted, since they’ll be able to move cargo faster, earning more money.

The ILWU is known as a tough union, said James Gregory, a University of Washington labor historian. “The whole way any union works depends a lot on theater,” he said. “Unions have to talk tough, otherwise they have no leverage and the employer does nothing to accommodate their interests.”

But as to the Portland strategy, Gregory said, “everybody would say it was a big mistake, and clearly turned into a nightmare.”

In Portland in 2012, Simon wrote in his jury instructions, union members drove trucks slowly, parked vehicles to block containers and reported bogus mechanical problems. But this time, instead of dealing with the coastal employers’ group, the ILWU was up against a subsidiary of Manila-based International Container Services Inc., a global port operations giant aiming to establish a U.S. beachhead.

The company has attracted criticism, which it disputes, for maintaining substandard wages and working conditions in less-developed countries. (Attorneys for ICTSI Oregon wouldn’t comment on the record, citing the ongoing litigation.) Yet one thing is certain: The company headed by Filipino billionaire Enrique Razon has plenty of money for legal fights.

Union leaders coveted positions that were held for years by workers with a Portland electricians’ local. The ILWU pushed ICTSI Oregon to give it the jobs after the company signed a lease with the Port of Portland in 2011 to begin running the container yard.

ICTSI said it could not reassign the jobs because the port controlled them. During four years of slowdowns, international shipping lines stopped calling on the terminal. ICTSI paid the port $20 million to get out of its lease and sued the union, listing that amount and other losses as damages.

If Simon upholds all or part of the award, the ILWU could appeal. But unless the union managed to post bond, ICTSI could start attaching the organization’s bank accounts for incoming dues money.

Appealing would be costly. Already, the union paid more than $2 million in 2018 for outside lawyers and expert witnesses, according to its annual filings with the U.S. Labor Department. The tab almost certainly ballooned last year, as attorneys prepared and went to trial.

A Chapter 11 filing by a union on the scale of the ILWU would be unprecedented, bankruptcy attorneys said. Previous filings involved local Teamsters and service workers chapters in California and Texas.

The ILWU is liable for 55% of the jury award — less than $3,500 per longshore member, a relatively low figure, but in caucus meetings so far, members have opposed individual assessments. Its Portland chapter, which has $150,000 in declared assets, is on the hook for the rest.

Union President William Adams told members in a Dec. 5 memo that a bankruptcy would not affect their contracts, working conditions, pensions, savings plans and health benefits. He wrote that union leaders would “be alert for any employer or politician who thinks they can take advantage of this temporary setback.”

James Doak, managing director of Miller Buckfire, a New York investment bank that advises on financial restructuring, agreed that pensions and other benefits would be apt to remain intact.

“The only thing that I don’t think is safe is that union reserve fund,” Doak said, referring to its $20 million in cash, an amount that the ILWU has kept low by running lean. The union has also sheltered its San Francisco headquarters building through ownership by a separate entity, the Pacific Longshoremen’s Memorial Assn.

For California businesses, 2020 will be a year of reckoning. Sweeping new laws curbing long-time employment practices take effect, aimed at reducing economic inequality and giving workers more power in their jobs.

Because the ILWU is funded by dues, “it’s the union membership that has to pay” for replenishing reserves after emerging from reorganization, Doak said. If members’ wages rose to rebuild the reserves, however, the increase could ultimately be passed along to consumers, he said.

A Chapter 11 filing would force the union to disclose details of its finances and operations, a disagreeable prospect for an intensely private organization. Debtors must give sworn testimony in response to questions from a bankruptcy judge and creditors and provide full accounts of operations, capital structure and events leading to bankruptcy, said Diane Lourdes Dick, a Seattle University School of Law professor.

“Submission of false or misleading information could provide grounds for dismissing or converting the case to a Chapter 7 liquidation, or appointing an examiner or independent trustee,” she said. “We think of bankruptcy as a kind of fishbowl.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.