Column: Don’t believe Facebook: The demise of the written word is very far off

- Share via

Facebook executive Nicola Mendelsohn shook up the online-o-sphere earlier this week with one of those offhand declarations that sound superficially profound for a moment or two but are vacuous at their core. In five years, she told a Fortune conference in London, her platform will probably be “all video,” and the written word will be essentially dead.

“I just think if we look already, we’re seeing a year-on-year decline on text,” she said. “If I was having a bet, I would say: video, video, video.” That’s because “the best way to tell stories in this world, where so much information is coming at us, actually is video. It conveys so much more information in a much quicker period. So actually the trend helps us to digest much more information.”

This is, of course, exactly wrong. We don’t mean her prediction about Facebook; in that, respect she’s talking her own book, since Facebook has made a big commercial bet on video. It’s her assertion that video conveys more information — and faster — than text that’s upside-down.

Unless our civilization fundamentally collapses, we will never give up writing and reading.

— Tech writer Tim Carmody, kottke.org

We’ll outsource the initial pushback to Kevin Drum of Mother Jones, who observes, “Video has many benefits, but information density generally isn’t one of them. … I can read the transcript of a one-hour speech in about five or 10 minutes and easily pick out precisely what’s interesting and what’s not. With video, I have to slog through the full hour.” That’s why his policy is never to click a link that goes to video.

Drum’s most salient point applies to the definition of the “information” people are seeking when they’re accessing video or text. “I read/view stuff on the Web in order to gather actual information that I can comment on,” he writes. Plainly, video is hopelessly overmatched by text in conveying hard information — facts, figures, data. A given video may arguably convey more “information” in bulk, but most of that is self-reinforcing context — color, motion, sound. The underlying factual information is relatively meager, in the same sense that the energy capacity of an electric-car battery can’t match that of an average gasoline fuel tank (the range of a fully charged Tesla Model S is about 250 miles, while that of a typical gasoline-fueled sedan can exceed 400).

Then there’s the challenge of extracting usable information from video vs. text. Video is a linear medium: You have to allow it to unspool frame by frame to glean what it’s saying. Text can be absorbed in blocks; the eye searches for keywords or names or other pointers such as quotation marks. Text is generally searchable online. Some programs can convert some videos to searchable form, but more often, the search is done via a transcript keyed to points in the video. Here, for example, is the full transcript of “Meet the Press” for May 29. Below is the video of the entire show. If your task was to find the moment when Chuck Todd first mentioned Trump University, which would you use to find it? (We’re not even counting the five commercial breaks.)

Give up? It’s at about the 24:43 mark.

The demise of text is often predicted, but the horizon seems to perpetually recede. Tech writer Tim Carmody puts his finger on the reasons why “text is surprisingly resilient” in an essay at Kottke.org: “It’s cheap, it’s flexible, it’s discreet. Human brains process it absurdly well considering there’s nothing really built-in for it. Plenty of people can deal with text better than they can spoken language, whether as a matter of preference or necessity. And it’s endlessly computable — you can search it, code it. … In short, all of the same technological advances that enable more and more video, audio, and immersive VR entertainment also enable more and more text. We will see more of all of them as the technological bottlenecks open up.”

He concludes that “nothing has proved as invincible as writing and literacy. Because text is just so malleable. Because it fits into any container we put it in. Because our world is supersaturated in it, indoors and out. Because we have so much invested in it. … Unless our civilization fundamentally collapses, we will never give up writing and reading.”

In predicting a world overtaken by video, Mendelsohn seems to be making a category error; she’s conflating visual with video. Facebook and other online platforms understand that their users are accessing their sites for their visual offerings, but that’s not the same as saying they’re doing nothing but watching clips.

That notion is contradicted by the findings of Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in its just-released Digital News Report for 2016.

The study found that most consumers of online news (59%) still gravitate to news articles — that is, text; only 24% said they accessed news video in the week before they were polled. “One surprise in this year’s data,” the report’s authors found, “is that online news video appears to be growing more slowly than might be expected.” The 24% figure “represents surprisingly weak growth given the explosive growth and prominence on the supply side.” In other words, there’s more video than ever before, but it’s not attracting a commensurately large audience.

Why not? For the same reasons Drum mentioned:

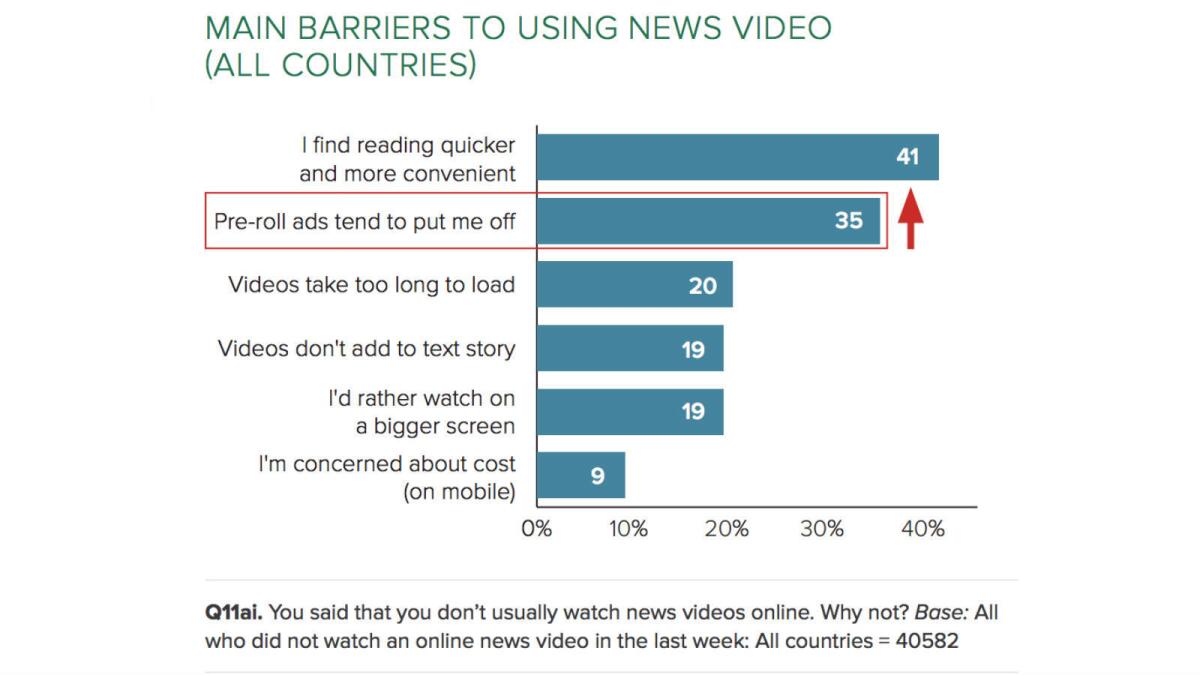

They take too long to load and unspool, and extracting the sought-after information is slower and more inconvenient than reading the written word. the number-two complaint — “Pre-roll ads put me off” — is another artifact of the linear nature of video, compounded by the cleverness of video providers in forcing you to watch through an entire ad, or three, before the clip even starts.

The secret underlying Mendelsohn’s claim is that there is something at which video is better than text: marketing.

The goal of advertising is not to impart information, but to keep it from the audience — to distract viewers from thinking too hard or asking questions. Video is ideal for that because that color, movement, noise, and light is all distraction. Video is entertainment, often of the empty-calorie variety. People love circuses, but they don’t normally go there to study zoology.

Indeed, it seems that most of the articles (yes, articles) written about the coming dominance of video looks at the phenomenon from the marketer’s standpoint: “A recent campaign from Volkswagen,” the Guardian reported last year, “saw a trio of its videos viewed a combined 155 million times.” Here’s a safe bet: those videos weren’t produced to explain why the car company had been faking emissions data, but to entice viewers to buy their cars.

Mendelsohn, by the way, came to Facebook from the advertising industry.

Certainly text and the written word will change to meet the demands of the new technologies through which we do our reading. That’s always been the case. Novels tended to be structured as a series of cliffhangers when they were read in monthly installments in a popular magazine; and in a different narrative form when they began to be printed in books sized to fit conveniently in a saddlebag, or valise, or before the fireplace. The length of news articles began to shrink when the reading audience began to migrate from newspapers that arrived on the stoop in the morning and were kept around to be perused at leisure, and toward smartphones and pads to be read between elevator stops.

That’s a testament to the infinite malleability of text. Text can conform to the relentless shrinkage of people’s attention spans; video can’t. Who will have time in the future to watch even a five-minute video, when they can learn so much more by scanning five paragraphs of text? “Bet for better video, bet for better speech, bet for better things we can’t imagine,” Carmody writes, “but if you bet against text, you will lose.”

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.