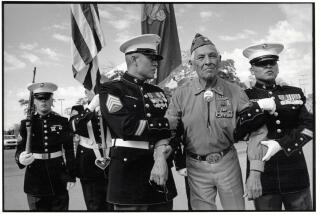

Iron Eyes Cody, Memorable Indian Actor, Dies at 94

- Share via

Iron Eyes Cody, the veteran Native American actor and humanitarian whose Hollywood career stretched back to the earliest big-screen westerns but who achieved perhaps his greatest success in a famous anti-pollution ad on the small screen, died Monday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 94.

It was during the production of a movie in 1970 that the part-Cherokee, part-Cree actor was approached with what would become his most memorable role--a job he initially declined.

In one of the public service commercials, Cody paddled a canoe past a belching smokestack and along a polluted stream before arriving at a busy highway. As he surveyed the urbanized landscape, garbage thrown from a passing car landed at his feet, drawing a single, bitter tear from his lined face. The camera stayed on Cody’s face while the announcer said, “People start pollution; people can stop it.”

“The final result was better than anybody expected,” Cody wrote in his 1982 autobiography, “Iron Eyes: My Life as a Hollywood Indian.” “In fact, some people who had been working on the project were moved to tears just reviewing the edited version. It was apparent we had something of a 60-second work of art on our hands.”

The campaign was an overwhelming success, racking up millions of dollars in donated air time. Shot in six days, the spots quickly made Cody one of the most familiar Native American faces in America--this after the actor had toiled in Hollywood for nearly half a century.

Originally called “Little Eagle,” Oscar Cody was born on an Oklahoma farm. He received his first taste of movie-making as a child when a Paramount Pictures crew used his family’s farm for location shooting in 1919. Within a year, the Codys relocated to Hollywood where Iron Eyes’ father, Thomas Longplume Cody, worked as a technical advisor on many early westerns.

After appearing in bit parts for a few years, Cody landed a small role in 1923’s “The Covered Wagon,” one of the most successful of the early silent westerns. The next year, while still in high school, he appeared in John Ford’s silent railroad drama, “The Iron Horse.”

After the success of the two films, Cody joined a cowboys-and-Indians stage show with actor Tim McCoy and departed for a lengthy tour of London and the South Pacific. Returning to Hollywood, he made friends with a young Gary Cooper, who encouraged Cody to try his hand at “real” acting in Victor Fleming’s silent drama, “The Wolf Song.”

Soon after, as production of quickie westerns escalated to meet the public’s growing demand, Cody found himself busy in front of the camera as an actor and behind it as an action sequence director.

During the day, Cody worked on such pictures as “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” “They Died With Their Boots On,” “Wagon Train” and “My Little Chickadee.” At night, he made the rounds of the Hollywood party circuit with stars like Cooper and Errol Flynn.

In 1936, Cody wed Bertha “Birdie” Parker, a Native American archeologist and occasional movie extra. During a sometimes tempestuous marriage, the couple raised two sons, Robert and Arthur, and a daughter, Wilma, who died in a childhood hunting accident. Bertha Cody died in 1978.

During the late 1930s, Cody spent several years leading a touring troupe of circus dancers, returning occasionally to work for director Cecil B. De Mille on such films as “The Plainsman,” “Union Pacific” and “Northwest Mounted Police.”

After the United States entered World War II, he left Hollywood for a local shipyard, working as a welder and monitoring suspicious activity for the FBI. “Each morning I donned my khakis, leather apron, hard hat and gloves and headed for the yards,” he wrote in his book. “I worked diligently and kept all my senses tuned to what was going on around me.”

After the war, Cody returned to movie-making, appearing in “The Outlaw” and “Unconquered” and alongside Bob Hope in “The Paleface” and “Son of Paleface.” In the early 1950s, he went to work for Walt Disney, starring in a studio serial titled “The First Americans,” and in episodes of “The Mountain Man,” “Davy Crockett” and “Daniel Boone.”

During the 1950s and ‘60s, he appeared in such western dramas as “The Devil’s Doorway,” “Tomahawk,” “The Savage,” “The Half Breed,” and “Nevada Smith.” Cody also appeared in “Broken Lance,” “The Last Wagon,” “Arrowhead,” “Yellow Tomahawk” and “Run of the Arrow.” He portrayed Chief Crazy Horse in 1954’s “Sitting Bull,” and two years later starred in the Disney feature, “Westward Ho the Wagons!”

In 1970, he appeared with Richard Harris in “A Man Called Horse,” and with Lee Van Cleef in “El Condor.” Other roles in the ‘70s and ‘80s included “Cockeyed Cowboys of Calico County,” “Grayeagle” and “Ernest Goes to Camp.” In recognition of his lengthy motion picture career, he was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1983.

The actor was also a familiar sight in the Tournament of Roses Parade for many years, appearing alongside Native American tribal leaders in a colorful equestrian unit.

Away from the movie cameras, Cody was an active humanitarian who contributed his energies and resources to numerous charities benefiting Native Americans. As one of his people’s most visible figures, he traveled extensively on goodwill missions, meeting with presidents, popes and heads of state.

“Nearly all my life, it has been my policy to help those less fortunate than myself,” he once said. “My foremost endeavors have been . . . to dignify my people’s image through humility and love of my country.”

Still, for all the decades spent in Hollywood among the likes of Cooper, Flynn and De Mille, the overnight success of the public service spot showed Cody that fame is often fickle.

“It certainly is funny how things work out,” he wrote. “Here I’d struggled in the movie business all my life, trying to carve out a name for myself, and just as I get into the big time with major roles I become recognized as the Indian who cries in a TV ad. The Great Spirit moves in mysterious ways.”

Funeral arrangements were incomplete.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.