- Share via

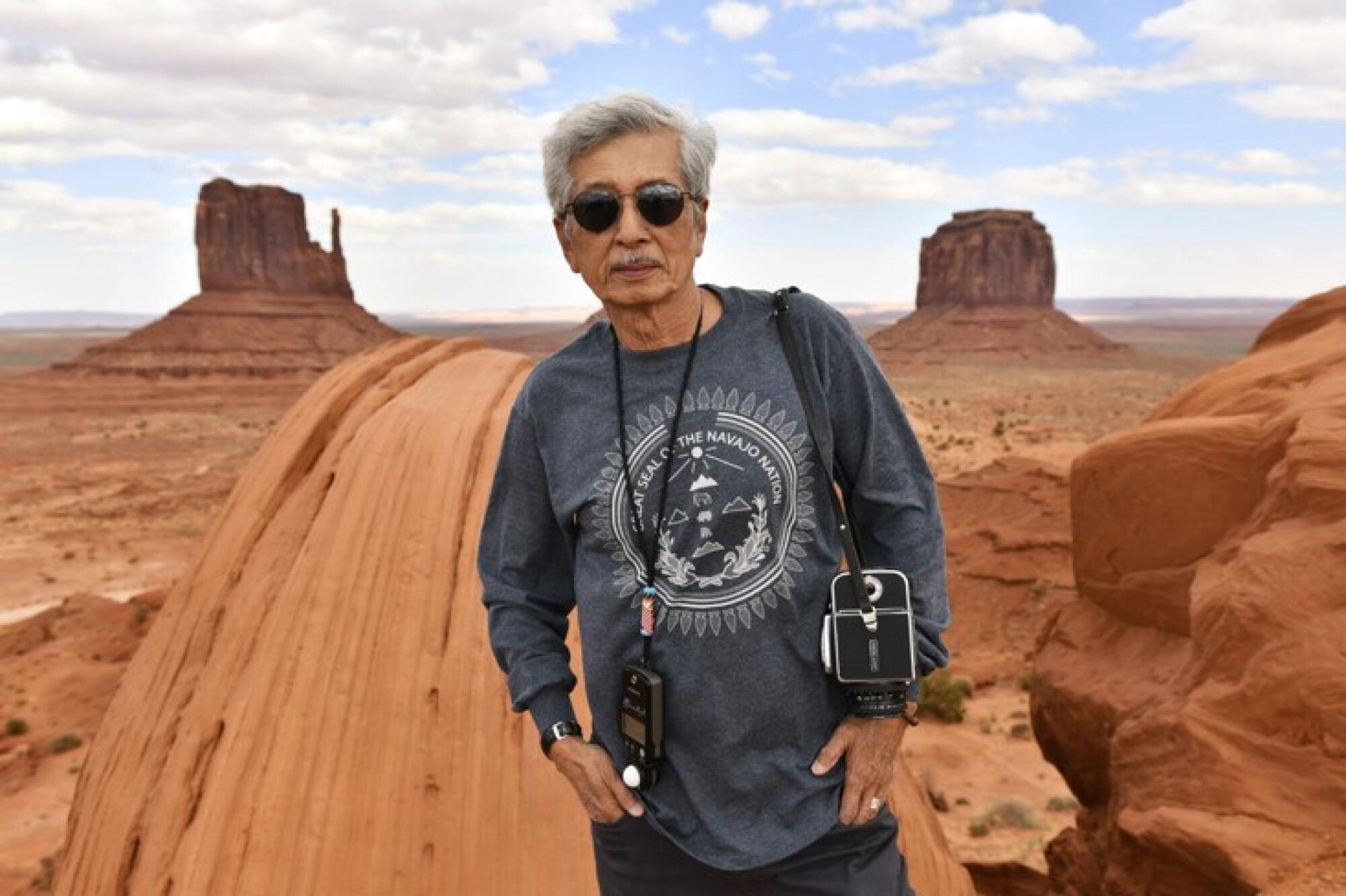

WINDOW ROCK, Ariz. — Kenji Kawano was hitchhiking on the Navajo Nation when Carl Gorman pulled over to give him a lift. During the drive, Kawano, then 23, explained that he’d arrived in the U.S. two years earlier with plans to travel the country taking pictures, hoping to build a portfolio that could land him a gig as a professional photographer.

“Where you from?” Gorman asked.

“Japan,” Kawano replied.

Then Gorman asked if Kawano had ever heard of the Navajo code talkers.

During World War II, a group of Navajo Marines had created a secret code based on their language to transmit telephone and radio messages in the Pacific. Japanese cryptographers had been breaking U.S. military codes — seemingly at will — and Navajo, a complex, little-known, tonal language, turned out to be a perfect solution to a dire problem.

The code was never broken, and on Iwo Jima alone, the code talkers, frequently referred to as America’s secret weapon during the war, sent more than 800 error-free messages in the fierce battle for the island. Before the end of the war, there were roughly 400 Navajo code talkers, and Gorman was one of them.

Marines who used language, not weapons, to fight a war?

“I thought it could be a good photo project,” Kawano said. He had no idea that this chance desert encounter in 1975 would take over his life.

Using Fuji film, an old pickup truck, a smattering of Navajo, a generous helping of humility and incredible tenacity, Kawano became the premier chronicler of this revered fraternity. For more than 40 years, he’s produced books of code talker photos and organized exhibits around the world, becoming their official photographer.

“A lot of the public recognition of these men and getting their names out there is due to Kenji’s photography,” said Zonnie Gorman, a code talker historian and the daughter of Carl Gorman, who died in 1998. “He developed a deep tie with these men and their families. It takes a lot to win over a Navajo, but once you do, you’re stuck with us for life.”

Time is running short — a corps of 400 has dwindled to three — but Kawano continues to document the final moments and memories of the men who participated in every major Marine assault in the Pacific, hoping his work will preserve their legacy for future generations.

::

Kawano, now 74, lives on the reservation with his 68-year-old wife Ruth, a Navajo. Their daughter Sakura is 41.

The walls of their tidy house in Window Rock, capital of the Navajo Nation, are covered in black-and-white photos. Vintage cameras sit on a shelf, and a cramped darkroom is just off the kitchen.

“These days you can see your picture right away,” Kawano said. “Taking pictures, driving home and developing the film takes forever,” but he likes “that moment when the picture is revealed.”

Some of his photos were on display at Window Rock’s Navajo Nation Museum last year in an exhibit titled “Navajo Code Talkers: Through the Lens of Kenji Kawano.”

“It takes a lot for me to have a non-Navajo’s work shown here,” museum director Manuelito Wheeler said. But Kawano has “spent the majority of his life here. He has a child who is part Navajo, and so from that perspective, and from a Navajo cultural perspective, he has become part of us. He is an in-law and that goes a long way here.”

Kawano was born in Fukuoka, Japan, before moving to Gotemba, which is near Mt. Fuji, when he was in third grade. He loved American movies such as ”Easy Rider” and “Midnight Cowboy” and westerns such as “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon.” He also loved photography and wanted to study it in college, but his father couldn’t afford it.

Undeterred, Kawano flew to Los Angeles in 1973, the first stop on what he hoped would be a great adventure. His goal was to land a full-time photography job.

Armed with a backpack, a Pentax camera and a portable film developing kit, Kawano found a cheap hotel in Little Tokyo where he could live and began taking pictures of the city and its inhabitants.

The owner of a nearby antique shop suggested he visit the Navajo reservation, which spreads across parts of New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. Kawano, who says he knew nothing about Native Americans at the time, bought a bus ticket to Gallup, N.M., and started his journey.

A local contact introduced Kawano to a Navajo family in Fort Defiance, Ariz., who took him in. He washed dishes and cleaned the house in return for a place to sleep. The rest of his time was spent taking photos on the reservation. Always black-and-white, always on film.

His next stop was tiny Ganado, Ariz., a reservation town, where he pumped gas and lived in a basement attached to the station. It had no heat, electricity or plumbing, and he used the toilet in the house next door. When Kawano’s mother saw photos of the place, she wept.

“When you are young, you don’t think too much or you will never act,” he said. “It was a big adventure for me.”

::

Kawano says he stood out on the reservation.

“The Navajo are curious by nature, especially the kids. They would follow me, this Asian guy walking around with a camera, and ask what I was doing,” he said. “You don’t see a lot of Japanese people on the reservation.”

He spoke little English and even less Navajo but took advantage of their curiosity to win their confidence.

Many of the Navajo he encountered were big fans of martial arts movies. At the time, films such as “Enter the Dragon” and “Billy Jack” were big hits, selling out theaters in Gallup for weeks.

“Bruce Lee was very popular in 1974. He was Chinese, but they didn’t understand the difference between Chinese, Japanese and Korean so they would always ask me if I knew kung fu,” Kawano said.

He didn’t, but he knew a few judo moves, which, he said, impressed the kids. When he was harassed after a football game in Ganado, he successfully fended off the attacker with some well-placed moves, cementing his reputation as someone not to mess with.

The Navajos gradually let Kawano into their world.

Once, at a Christmas party, he met a father and son who sang traditional Navajo songs. They agreed he could photograph them at their house. “Years later the son came to me and said, ‘Do you remember me?’’’ Kawano recalled. “He said his dad had passed away, but he still has that picture I took to remind him of him.”

Photography did not pay the bills, so Kawano also worked as a janitor, maintenance man and school photographer at the now-closed College of Ganado, where most of the students were Navajo.

He met Ruth Williams at the college in 1976. They would go for walks and he’d sing her songs in Japanese. They married two years later.

“Everything about him was closely tied to the way I was brought up — being disciplined, setting goals and being active in attaining those goals,” said Ruth, a registered nurse and a photographer. “That was really important to me.”

Her father, an Army veteran, accepted Kawano immediately.

“My mother had her concerns, but I think after you started coming around, chopping wood, getting water, they get to know you,” Ruth said. “They saw Kenji as a human being, and ultimately that’s all that mattered.”

::

While living in Ganado, Kawano routinely hitchhiked to Window Rock for photo supplies — which is how he met Carl Gorman.

“Back in the day, that was my dad’s thing, picking up hitchhikers,” Zonnie Gorman said. “He loved to have conversations and loved to engage with people, especially somebody so very different.” At the time, her father was the head of the Navajo Code Talkers Assn., and he introduced Kawano to some of the others.

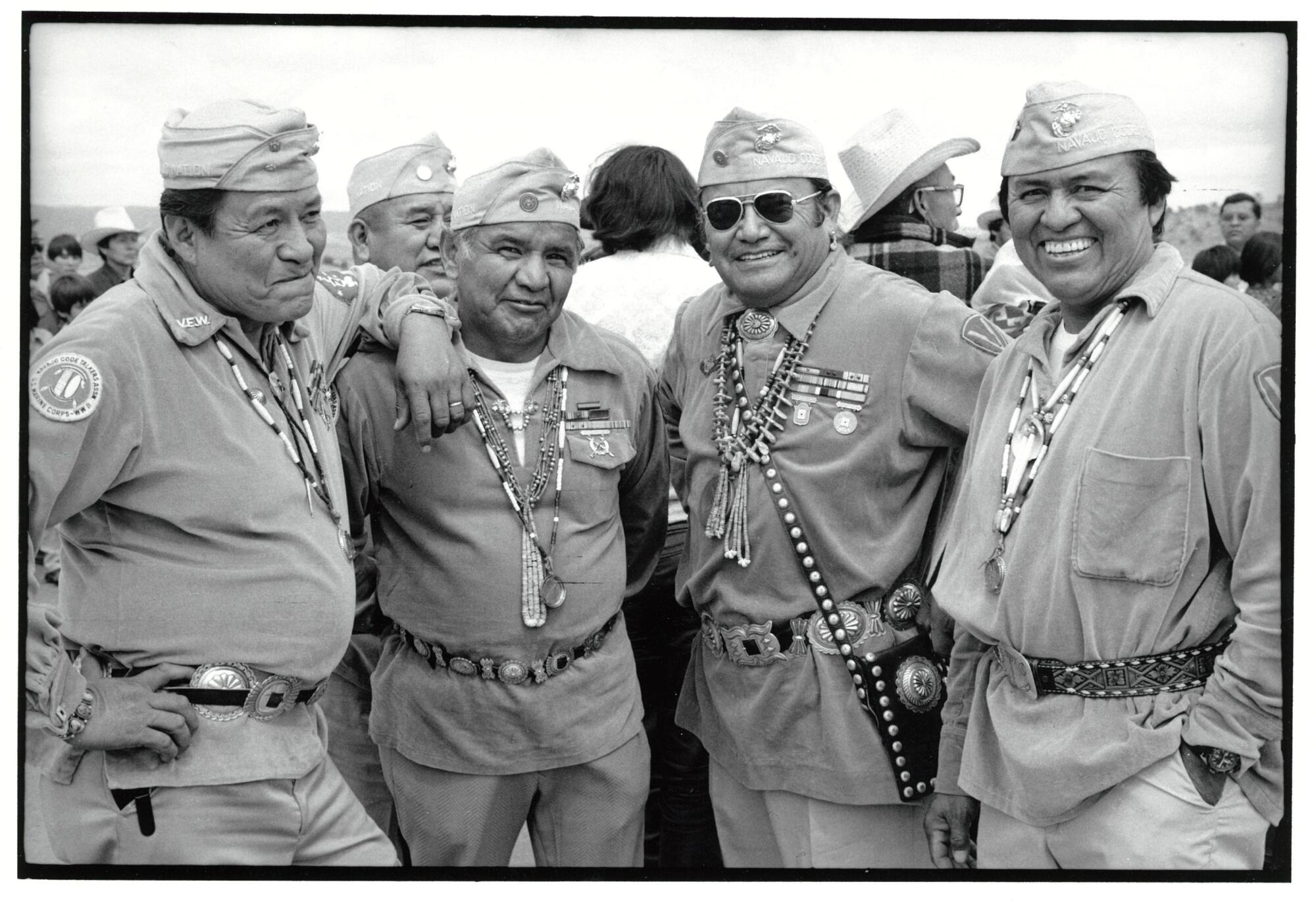

The code talkers were not well known then. After the war, they were sworn to secrecy about the program until it was declassified by the federal government in 1968. Kawano said the code talkers held their first reunion that year and began taking part in the annual Navajo Fair around 1970.

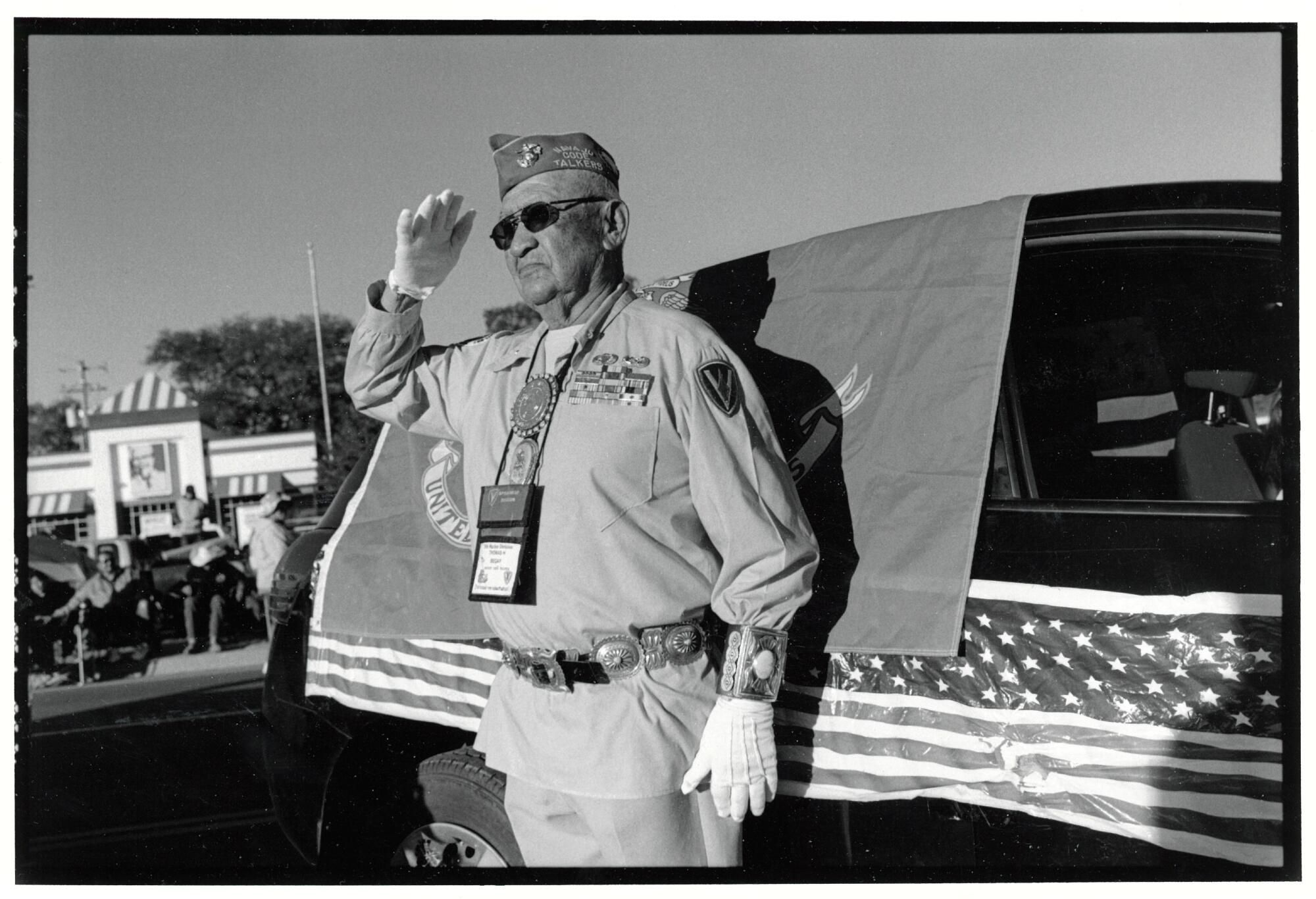

In 1982, then-President Reagan declared Aug. 14 National Code Talkers Day, which encouraged more of the men to share their experiences. The Navajo Nation had already initiated an annual parade in their honor.

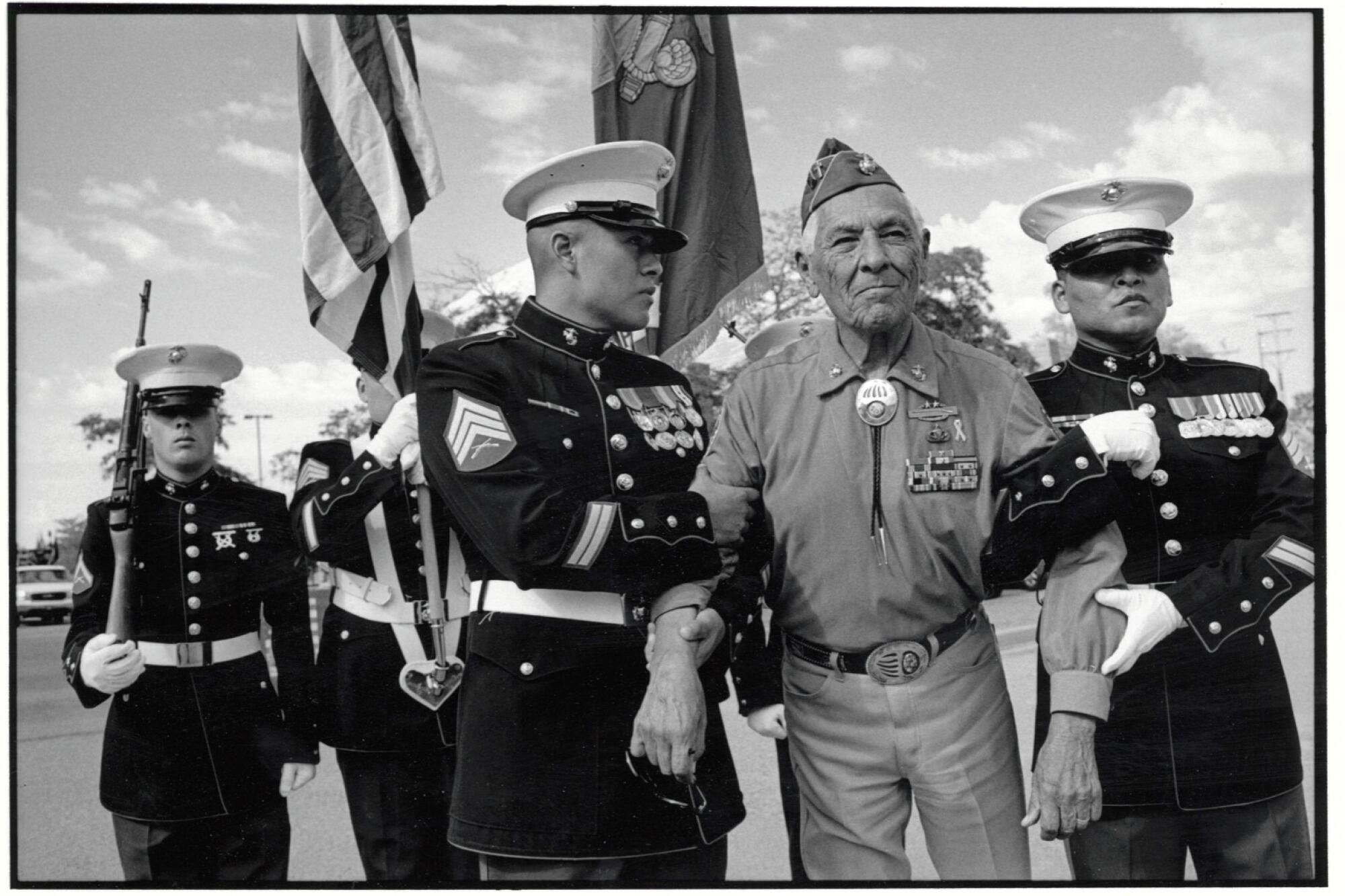

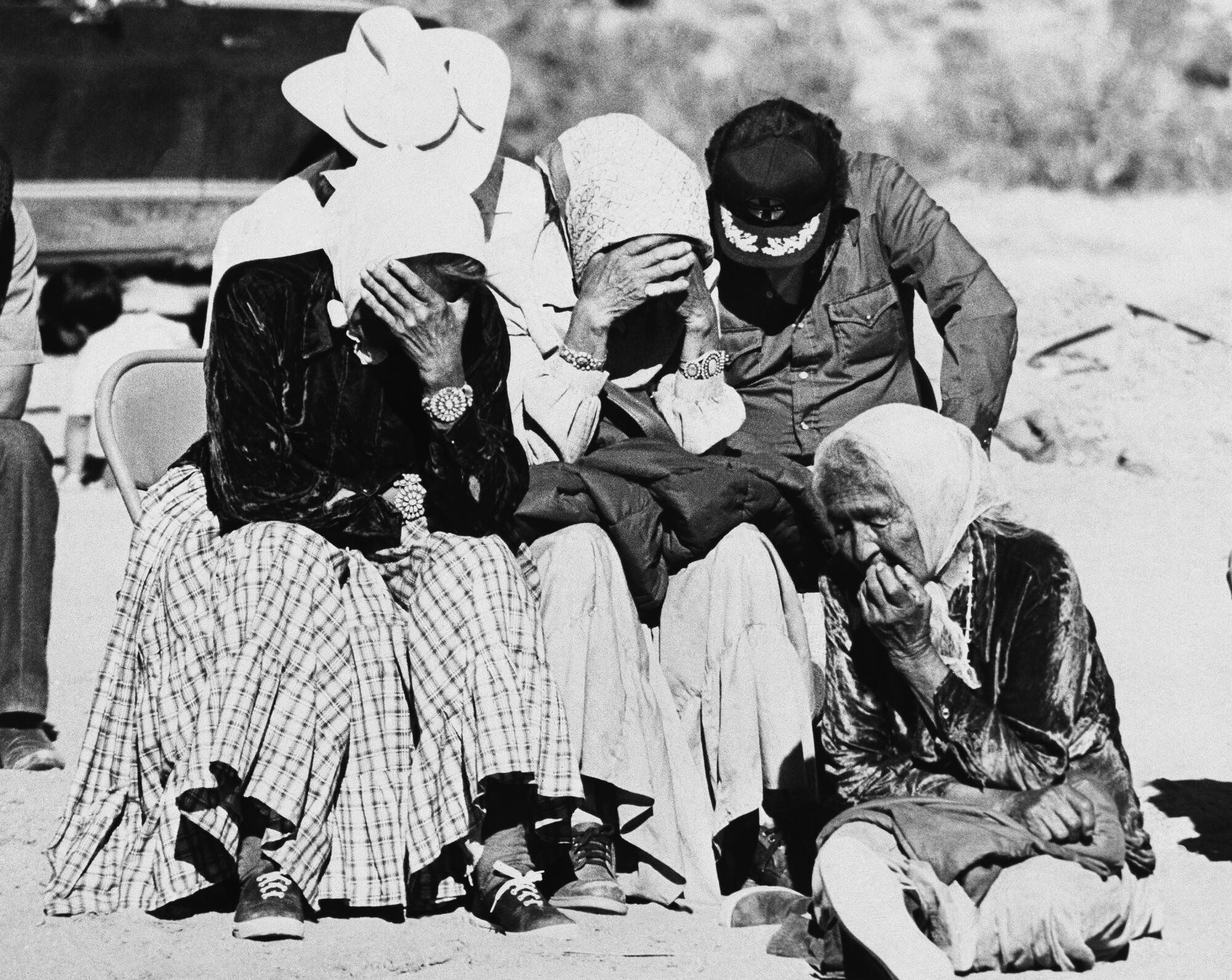

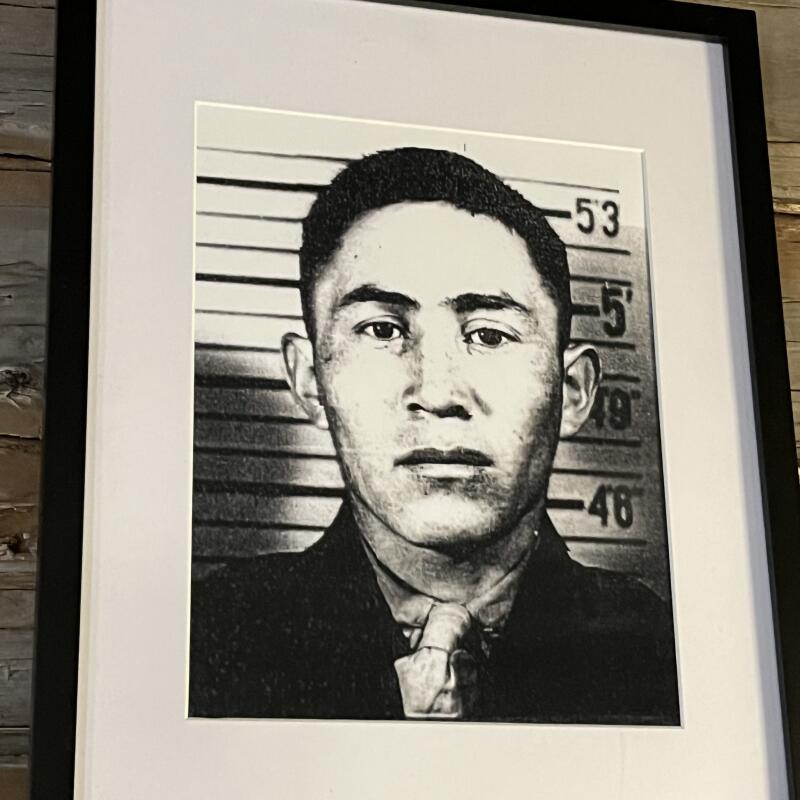

Kawano took pictures of the men at the parades, but he wasn’t satisfied. He wanted portraits that were distinctively Navajo, so between 1975 and 1989 he tracked down as many of the 200 or so survivors as he could to create individual portraits. He eventually photographed 110 code talkers.

In the 1980s, only about 20% of Navajo homes had telephones. If he found a code talker’s address, Kawano would just show up. A few of the men he encountered refused to cooperate. They’d had friends who’d been killed by Japanese soldiers, and his request didn’t sit well. But most of them eventually said yes.

“Sometimes I would drive for hours, knock at the door and there was no one there,” Kawano said. “If they were home, I would introduce myself and tell them about my project. Most were happy to share their lives and experiences. Here was their old enemy and yet they would agree to work with me.”

Kawano photographed code talkers in front of traditional Navajo dwellings. He stood them beside sheep, a central part of tribal life. His photos were intimate; their lined faces, expressive.

He was a perfectionist. He’d drive three hours or more on a reservation the size of West Virginia for a photo, explaining, “When I developed the film at home and wasn’t happy, I would drive three hours back to retake it.”

His first book of photographs, called “Warriors: Navajo Code Talkers,” was published in 1990, and that led to exhibits in Japan, Germany, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Virginia, Albuquerque, the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs and the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock.

He asked every man he photographed for the book to write down one memory of the war:

“I participated in the bloody battle of Iwo Jima … They told us to secure communications and telephone wire under combat conditions on the island within three days. But it took about a month,” Teddy Draper Sr. wrote.

Wilson Price recalled how “we all cheered and jumped around” when the American flag was flown atop Mt. Suribachi on Iwo Jima.

“While I was stationed in Guam. I saw a soldier step on a landmine. Both of his legs and one hand were destroyed,” John Kinsel Sr. wrote. “He asked for a smoke, saying, ‘I still have one hand.’”

After the book published, code talkers who’d been initially reluctant to be photographed changed their minds, and Kawano was besieged with requests. He published another book of portraits and aerial photographs of the Navajo Nation. He followed that with a book focused on Navajo women.

Kawano also wrote a book in Japanese about living on the reservation, prompting NHK, Japan’s largest broadcast network, to create a 2004 documentary on his life called “Japanese Who Live Far Away from Japan.”

“They couldn’t understand why I would live here,” Kawano said. “But I found what I loved here, not in Japan.”

The code talkers anchored his life here. He spent hours talking and sharing stories, and they tolerated his fussiness, looking for just the right angle, just the right light. Kawano’s humble, reserved manner mirrored their own, relatives of the men observed.

“I spent more time with them than my own father,” Kawano said.

::

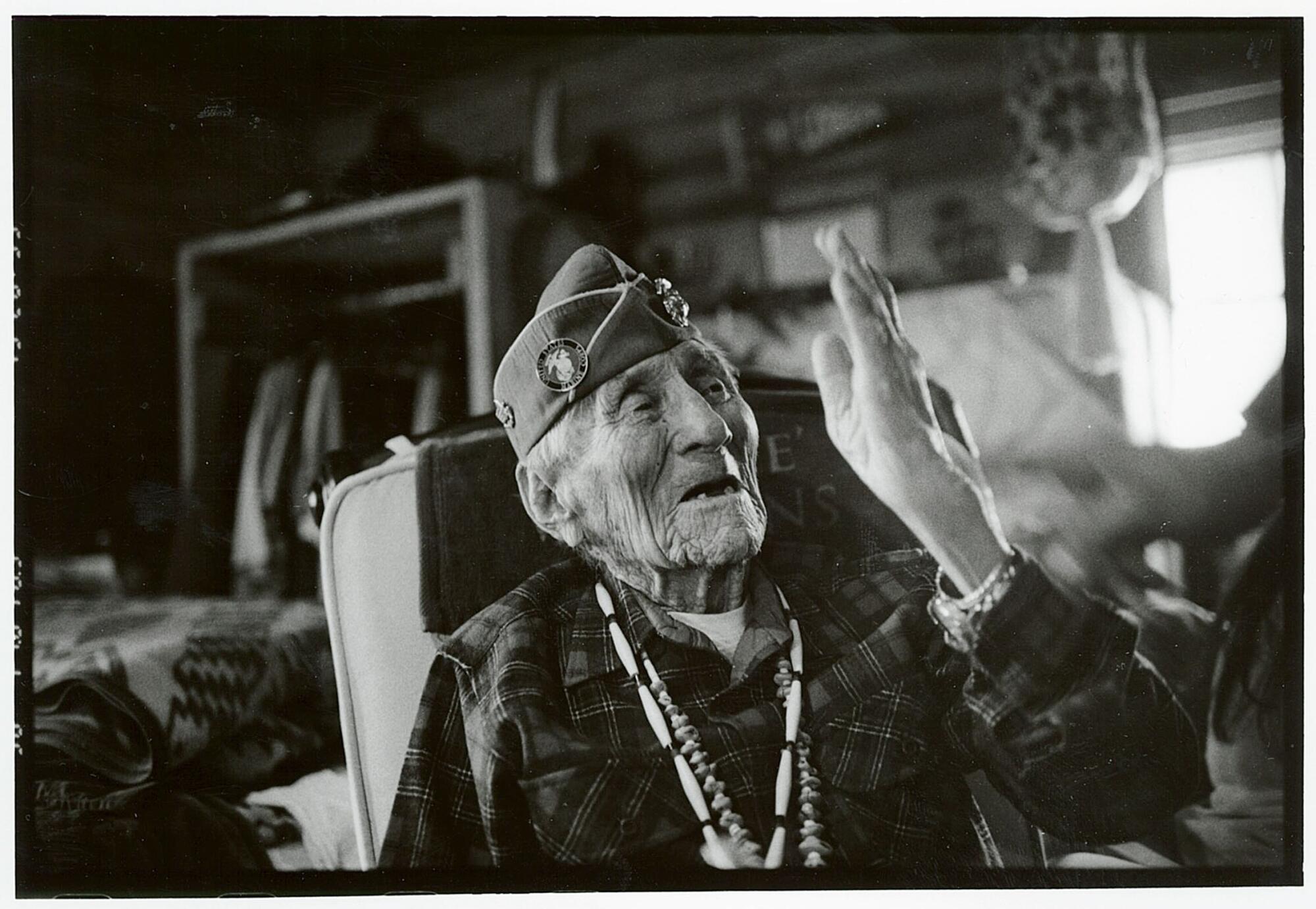

John Kinsel Sr., 107, the oldest of the three surviving code talkers, lives in rural Lukachukai, Ariz., with his son Ron, 71, in a cabin he built in 1950.

A Kawano photo of Kinsel hangs above his bed. Feathers dangle from the ceiling, and traditional medicines and herbs in small leather pouches are close by. When Kinsel recently began seeing visions of his late horse Yoyo running toward him, a medicine man held a ceremony to dispel the phantoms.

Kinsel fought on Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal and other Pacific battlefields. Now frail and hard of hearing, he spends most of his time sleeping, fueling himself with mutton stew — his “medicine” — his son says.

Questions had to be shouted. His answers were halting. But he lit up at the mention of Kawano, clutching a visitor’s arm and leaning in close.

“Kenji has used his pictures to show the world what the code talkers did,” Kinsel said, propped up in a chair and wearing a turquoise belt and necklace. “If it wasn’t for him, we would not be known.”

1

2

1. Kenji Kawano has been documenting the Navajo code talkers for half a century. (David Kelly / For The Times) 2. A portrait of a Navajo code talker. (David Kelly / For The Times)

Back in Window Rock, Kawano flicked through some of his photos. He said he has enough material for four or five more books. He knows these are the last days of the code talkers, and he hopes his work brought their stories to a wider world.

“I accomplished more than I expected,” he said quietly. “The story won’t end when they are gone; the story will go on.”

Kelly is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.