- Share via

MEDYKA, Poland — He put his job as a structural engineer in Poland on hold, loaded up his Volkswagen Golf with food, gear and sundry supplies, and was on the road back to his homeland — Ukraine, now a battlefield.

“I am going to fight the Russians,” said Oleksandr Zhuk, 55, as he waited behind the steering wheel in a mile-long line of eastbound vehicles in this Polish border town. “I have experience. I have fought them before. I want to be there.”

Swaths of Ukraine have fallen into Russian hands. Corpses scattered in the snow. Rockets rain daily on civilians. The capital, Kyiv, waits in cruel limbo for advancing Russian forces.

Since Russia launched its invasion nine days ago, more than 1.3 million Ukrainians have streamed westward into Poland and other Eastern European nations, the largest flow of European refugees since World War II. More than half fleeing Ukraine have come into Poland.

The seemingly nonstop exodus of mostly women and children — most military-age men, defined as those 18 to 60, have been barred from leaving Ukraine — has stunned the world. It has also posed huge logistical challenges for Poland and other nations bordering Ukraine.

But there is also growing movement headed the other way, of people, vehicles and merchandise entering Ukraine. Aid caravans and volunteer fighters like Zhuk are among the eastbound traffic.

Zhuk plans to integrate into the government-backed forces opposing the Russian advance. He said he had already fought the Russians in the disputed eastern Ukrainian territory of Donbas, a conflict that has cost 14,000 lives since 2014, according to Ukrainian authorities.

“I know how to fight the Russians,” said Zhuk, speaking from behind the wheel of his car. “I have been there myself.”

It is unclear how many Ukrainians have thus far heeded the government’s call to return and fight.

But a steady stream of men has made its way into Ukraine in recent days via the border here, either in personal vehicles or utilizing the concrete pedestrian footpath to the border. They are mostly members of the far-flung Ukrainian diaspora, stretching from Poland to Norway to the United States, now called home to duty. Some carry military equipment, including body armor, clearly visible in bags and packs. Others lug their gear in rolling suitcases or duffel bags.

“We all feel a sense of responsibility, to fight for our homeland,” said Oleg Roman, 47, a Ukrainian native now living in northern Italy, who was walking toward the Ukrainian border Saturday. “When this invasion first started, there was a sense of shock. Then it became a feeling of responsibility.”

Among the things he carried, Roman said, were antiballistic boots, meant to protect feet and legs from mines and other blasts.

Almost 800,000 Ukrainians have fled to Poland as Russian forces push farther into Ukraine.

Numerous non-Ukrainians were also headed to Ukraine in what is being referred to as the creation of a kind of Ukrainian international brigade.

Social media posts celebrate the global recruitment.

“People from all over the world have come here to help defend Ukraine,” read a recent post on Twitter from a volunteer who described himself as a reservist in Finland’s military, now in Ukraine. “My bunkmates are Norwegian and American. There is still plenty of room for more!”

Three French medics were among those making their way into Ukraine on Saturday.

“This is Europe, we must make a stand,” said Vincent, 25, from Toulouse, who declined to give his last name for security reasons.

Among those offering their services to Ukraine in recent days was a 25-year-old man from San Bernardino who declined to provide his first or last name, citing privacy concerns, as he waited near the pedestrian entrance. He said he was a search-and-rescue specialist but had no military experience. He carried a backpack stuffed with more than 70 pounds of gear, including a shovel and backpack — the latter one his father had used in the military — and bandages, wound dressings and other materiel to be donated to Ukraine.

“It’s something that I believe in strongly,” he said of his decision to support Ukraine, as he adjusted his pack before entering the checkpoint. “I felt a calling.”

However, he said that his family had been in near-universal opposition to his decision.

“Some people are really mad at me,” he said, declining to elaborate.

Along with volunteer fighters, vehicles stuffed with aid — blankets, food, paper products, sleeping bags — are entering Ukraine through this Polish border town, which marks the largest crossing between the two nations. Much of the aid is donated by people across Europe.

Some vehicles carry placards declaring, “Stand With Ukraine” or “Stop Putin.”

“There’s a real sense of solidarity, a feeling that we need to help,” said Daniel Baird, who came from Denmark in a two-day road trip at the helm of a Volkswagen van packed with goods for Ukraine, as was a connected trailer. “People feel a threat to democracy. Everyone wants to help.”

Sitting in the passenger seat was Bwalya Sorensen, a native of Zambia who now lives in Denmark and helped in the aid effort.

“What is happening in Ukraine, it feels very close to home,” said Sorensen. “This is Europe. This is not so far away.”

Even as the aid and fighters flowed in, refugees continued to enter Poland. Many of the fleeing families were multi-generational — grandparents, their children and grandchildren. Leaving behind husbands, brothers and fathers was wrenching, they emphasized. Tearful leave-takings have been occurring daily on the Ukrainian side of the border.

“My husband hated to leave us alone, but he knew he had a duty to stay,” said Golyna Galina, 32, a psychologist who fled Kyiv along with her mother, 2-year-old daughter and sister-in-law. “We wanted to stay, but then the bombings started, close to our house. I felt responsible for my daughter. We couldn’t expose her to that.”

The four sat in the bitter cold waiting for a bus to the northern Polish port city of Gdansk. They faced at least an eight-hour wait. From Gdansk, the family would take another bus to the Baltic nation of Lithuania, where they have family to stay with. Galina and family were among tens of thousands waiting for transportation out of the border zone, often outdoors, exposed to the elements.

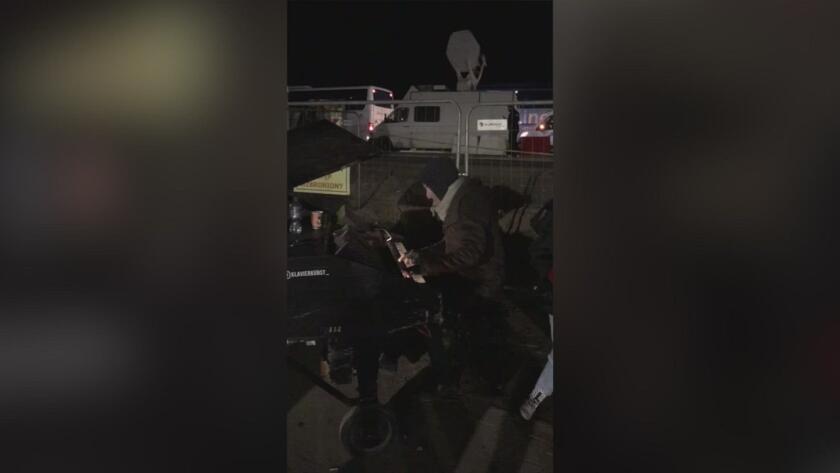

Davide Martello plays Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” as Ukrainian refugees stream into Poland. (Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

Trying to provide some measure of comfort amid all the distress was Davide Martello, 40, an Italian musician who played a piano near the exit point where many refugees have entered Poland.

He brought his piano — emblazoned with a peace sign — to the hectic site, hoping his easy-listening repertoire would bring some relief.

“All these people passing, they have heard bombs, cannons, MIGs. Now I want them to hear music,” said Martello, speaking as he sat at the keyboard between musical numbers. “And I also want to send a message of love to Vladimir Putin. Maybe it’s going to open up his heart a little bit. I don’t know.”

Special correspondent Liliana Nieto del Rio contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.