Coronavirus Today: Todayâs COVID-19 forecast calls for ...

Good evening. Iâm Karen Kaplan, and itâs Tuesday, Jan. 24. Hereâs the latest on whatâs happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Southern California isnât known for wet weather, but Iâll bet you own an umbrella. It may spend most of the time in a closet, but if the forecast calls for rain, you donât leave home without it.

Someday, your face mask might be like your umbrella.

If public health forecasters spot a worrisome uptick in coronavirus activity, you can take care to mask up when you head to the grocery store or a parent-teacher conference. Perhaps the health warning will prompt you to relocate your dinner date to an outdoor table or work from home until the threat has passed.

This vision of the future relies on having a way to predict COVID-19 outbreaks before they happen. These forecasts will have to be reliable â if there are too many false alarms, people will simply ignore them. Theyâll need to be tailored to specific geographic areas so people will feel theyâre relevant, and theyâll need to be available early enough for preventive behaviors to make a difference.

Thatâs a pretty tall order. Lucky for us, scientists are working to make it a reality.

A team led by Mauricio Santillana, director of the Machine Intelligence Group for the Betterment of Health and the Environment at Northeastern University in Boston, shared plan for such a system last week in the journal Science Advances.

As my colleague Melissa Healy reports, the teamâs viral forecasts are based on hundreds of sources of digital information. These include:

⢠Online searches for COVID-related terms like âfever,â âcoughâ and âquarantine,â along with the time stamp for each query. (One particularly useful warning sign was the number of times people asked search engines, âHow long does COVID last?â)

⢠Twitter messages containing words like âcoronaâ and âpandemic,â plus geolocation data for each tweet.

⢠Location data from smartphones, which indicates how often people are leaving their homes and how far theyâre going.

⢠The number of times people used the Apple Maps app on their iPhones, another way to tell whether people are staying in or going out.

Youâd need a pretty big brain to digest and synthesize all this material. Santillana and his colleagues have powerful computers to help them.

The team developed software capable of winnowing and interpreting the heaps of data it collected. The software uses the data to build a map of coronavirus contagion, then checks that map against the actual experience of 93 counties over two years of the pandemic. Those checks help the software refine its understanding of the patterns that signal infections, illnesses and outbreaks.

The computers performed impressively in tests. Santillana and his colleagues fed their system real-world data and waited to see if it would recognize the early signs of 367 county-level outbreaks that actually happened. Sure enough, the program flagged 337 of them â a success rate of 92%.

But the other 30 outbreaks werenât necessarily failures. In 23 cases, the software realized that an outbreak was afoot at the same time as human public health officials, according to the study.

The fast-spreading Omicron variant was a little more difficult to get ahead of. In the teamâs tests, the program gave early notice of outbreaks 87% of the time.

The systemâs performance was âvery promisingâ thanks to sound use of âmachine learningâ methods, said New York Universityâs Anasse Bari, an expert in the field who was not involved in the work. But he cautioned that it would be risky to depend on something this new to protect the public during a health emergency on the scale of the pandemic.

On the other hand, itâs clear that new tools are needed. A recent evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Preventionâs COVID-19 forecasting abilities said the agency âfailed to reliably predict rapid changesâ in illnesses and hospitalizations. Even Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the CDCâs director, agrees that the nationâs public health agency needs to do better.

Santillana said heâs ready to help. The methods his team used to forecast COVID-19 outbreaks can be applied to other diseases too.

âWeâre looking beyondâ COVID-19, he said.

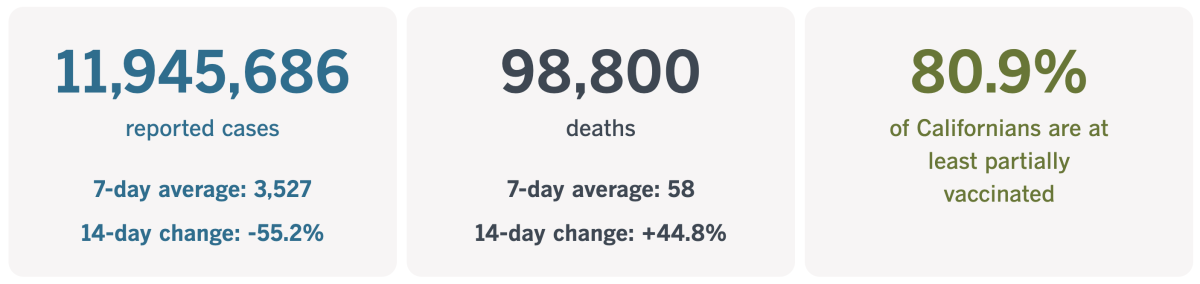

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 2:45 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track Californiaâs coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts â including the latest numbers and how they break down â with our graphics.

Music as medicine

The pandemicâs early lockdown days were characterized by stress, fear, worry, depression and other mental health difficulties. Not only were we facing a host of new uncertainties brought on by a mysterious virus, but stay-at-home orders prevented us from seeing friends, going to the movies or doing a variety of other things that would normally help us blow off steam.

The list of pastimes that are safe to pursue while trying to bend the curve includes listening to music. And now we have medical evidence that music can âimprove health and well-being on the population level during times of crisis,â according to the authors of a study published this month in the medical journal JAMA Network Open.

In the early months of the pandemic, a team of researchers had volunteers from Austria and Italy download an app that asked them questions five times a day for a week. The queries appeared at random times during specified intervals, and participants had 30 minutes to respond.

Participants were asked to rate their stress levels on a scale of 0 to 100. The app also invited them to score themselves on a continuum from âunwellâ to âwell,â âdiscontentedâ to âcontented,â âtiredâ to âawake,â âwithout energyâ to âfull of energy,â ârestlessâ to âcalmâ and âtenseâ to ârelaxed.â

At each check-in, participants were also asked if they were âdeliberately listening to musicâ at that moment and, if not, whether they had turned on tunes since the last time they were asked. If the answer to either question was yes, the app asked them to rate where their tunes fell on a 0-to-100 scale from âsadâ to âhappyâ and from âcalmingâ to âenergizing.â

A total of 711 people answered these (and other) questions in the spring of 2020, responding to the app a total of 19,641 times. On nearly a quarter of those occasions, the participants were or had recently been listening to music. That provided the data the researchers needed to assess whether music had the power to pull people out of their lockdown blues.

The answer, it seems, is yes. After people listened to music, they tended to report lower levels of momentary stress. Not only that, but when people listened to music while experiencing heightened stress, they experienced âa significant decreaseâ in their stress levels.

The researchers also found that after listening to music, people reported higher levels of wellness, contentedness, wakefulness and feeling energized. In addition, people who had low energy levels when they pressed play tended to report higher energy levels in subsequent check-ins.

The benefits of listening to music were particularly pronounced in those with high levels of chronic stress. For them, turning on the tunes was associated with a bigger boost in wellness, contentedness, wakefulness and energy than it was for people with less chronic stress.

Finally, the researchers found that when people listened to music that was happier than their usual fare, they became less stressed, felt more calm and relaxed and experienced a wellness boost.

Earlier studies have found that people who listened to music during the pandemic were less likely to be depressed or experience other forms of psychological distress. Music fans were also found to be more satisfied with lockdown life, even compared with people who passed the time by bingeing movies.

The difference with this study is that the app allowed researchers to measure participantsâ mental well-being right after they listened to music â and to do so in real time, instead of asking them to recall their activities and emotions months after the fact.

The report âextends previous research that has highlighted the health benefits associated with music and the value of music in coping with psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown,â the researchers wrote. Especially for people experiencing high levels of stress, they added, âmusic listening might be considered an easy intervention.â

Since the study participants were recruited through online ads and social media instead of chosen at random, itâs not clear how well these findings would apply to the population at large. The participants ranged in age from 18 to 80, with a median age of 27. Nearly 70% were women, 43% were in the workforce, and 33% were full-time students.

Still, thereâs undoubtedly something universal about the healing power of music, the authors wrote: âHistorical evidence suggests that, particularly in times of crisis and disasters, individuals across cultures turn to music to lift their mood and to increase feelings of social connectedness.â

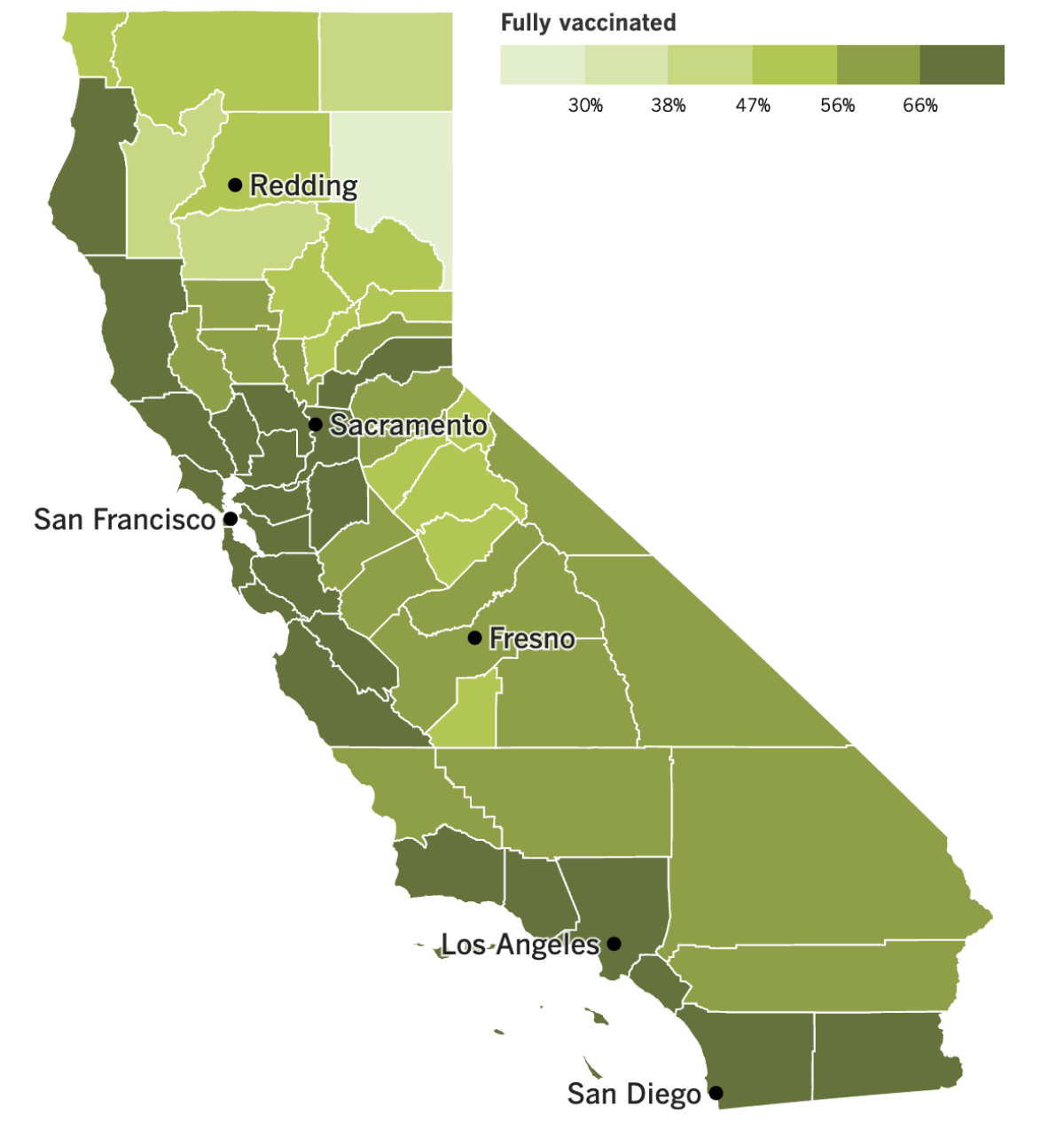

Californiaâs vaccination progress

See the latest on Californiaâs vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

Los Angeles County, give yourself a big pat on the back. When it comes to the coronavirus, it looks like youâre doing everything right.

Reported case counts, hospitalizations and deaths are dropping. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rewarded these signs of progress by moving the county into the âlowâ COVID-19 community level column. That designation doesnât mean the coronavirus is no longer a concern, but it does mean itâs not putting undo stress on the local healthcare system.

âWe have a very different January than expected,â L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said last week. âFor that, Iâm grateful.â

As of Thursday, the county was averaging 76 cases per week per 100,000 residents â a rate thatâs âsubstantial,â as opposed to âhigh.â In addition, the number of hospitalized patients with coronavirus infections has dropped 31% over the last two weeks, and deaths over the past week have dropped to 139, according to the Timesâ Tracker. Thatâs down from a seasonal peak of 164 for the week that ended Jan. 13.

Experts arenât sure whatâs responsible for our good fortune, but itâs likely a combination of factors. Many residents have immunity thanks to recent infections or doses of COVID-19 vaccine. Antiviral drugs like Paxlovid and molnupiravir probably prevented many high-risk COVID-19 patients from becoming seriously ill. We may have even heeded calls to mask up indoors and move large gatherings outdoors.

Itâs also possible that some of the improvement is illusory â there are likely folks who test positive at home and donât share the results with county officials, or people whose illnesses are so mild that they never take a coronavirus test at all.

Conditions across the state generally mirror those of its largest county. Statewide, the number of new cases has plunged 55% over the past two weeks, and hospitalizations are at their lowest point since November.

However, an average of 58 Californians have died of COVID-19 each day over the past week â a 45% increase from two weeks ago. The weekly death toll (406) is now higher than the peak of the summerâs BA.5 surge (396) but still well below the peak of the initial Omicron wave last winter (1,827).

Thirteen other California counties joined Los Angeles in moving from the medium to the low COVID-19 community level last week. In Southern California, only Orange, San Diego and Imperial counties remain in the medium level. Theyâre joined by 14 others in the central and northern parts of the state.

Altogether, 71% of Californians live in counties with a low COVID-19 community level, up from just 28% this time last week.

All this good news is prompting some folks to ask whether the state has avoided a third consecutive devastating winter surge.

After seeing a post-Thanksgiving rise in case counts, health officials braced for the worst. Instead, many Californians celebrated their first (mostly) normal holiday of the pandemic without fueling a record-setting outbreak.

Still, Ferrer isnât ready to say the danger has passed.

âThereâs still people for whom COVID is going to remain a really big concern, and theyâre going to continue to need to do everything they can to avoid getting infected,â she said. âWe still have a lot of virus in our communities, but we are definitely in a promising place.â

All that could change if a new variant comes along with the power to overcome our hard-won immunity or evade our workhorse treatments. Experts are keeping a close eye on the Omicron subvariant known as XBB.1.5, which is estimated to account for 49% of coronavirus specimens in the U.S., according to the CDC.

XBB.1.5 â also known as the âKraken variantâ â has been growing steadily in the region that includes California, Arizona, Nevada, Hawaii and the Pacific island territories. But even here, itâs estimated to be responsible for only about 24% of coronavirus infections over the past week, the CDC says.

In Washington, D.C., officials at the Food and Drug Administration are considering a move to treat COVID-19 boosters like the annual flu shot. They have laid out a simplified approach for future vaccinations that wouldnât require Americans to keep track of how many total doses theyâve had or how much time has passed since their most recent jab.

Under the FDAâs proposal, most adults and children would get a yearly booster to rev up their immune systems and prepare to meet a more recent version of the coronavirus. People with weakened immune systems would likely need a two-shot series to get the same protection. So would very small children.

FDA scientists will discuss the plan with the agencyâs panel of vaccine advisers Thursday. The panelâs recommendations arenât binding, but they are usually taken into consideration.

And finally, the COVID-conscious nation of Japan will soon downgrade the diseaseâs legal status so that itâs equivalent to the flu. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said last week he planned to make the change in the spring.

For now, Japan considers COVID-19 a Class 2 disease, putting it in the same category as tuberculosis and SARS. That designation triggers a host of restrictions, including a requirement that COVID-19 patients be treated at specialized facilities.

Once COVID-19 is categorized as a Class 5 disease, patients will be able to see doctors in regular hospitals, and a host of antivirus measures will be relaxed. Health Minister Katsunobu Kato said the goal is to treat COVID-19 like any disease â not to ignore it altogether.

âChanging its classification doesnât mean coronavirus is gone,â Kato said. âWe still need everyone to take voluntary measures by using masks and precautions.â

Your questions answered

Todayâs question comes from readers who want to know: What is a COVID-19 case cluster?

In California, the short answer is that itâs a group of three or more people in a setting like a workplace or a school who have coronavirus infections within a two-week period that have a plausible epidemiological link.

Ideally, those infections would be confirmed with a laboratory test. But they can also count if a person has COVID-19 symptoms, gets a positive result on a rapid test and/or has an epidemiological link to other infected people in the same setting. In addition, those three (or more) infected people canât be in close contact with one another, nor can they be linked to any other outbreak.

The part about close contacts doesnât apply to outbreaks in places like dormitories, jails, homeless shelters or overnight camps. Since the residents live in shared spaces, theyâre treated as if theyâre close contacts. Infections among both residents and staff members count toward the total size of a cluster.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health uses the stateâs definitions when it tracks case clusters in workplaces and in schools.

Other states have their own definitions. Some require only two linked infections in a two-week period, while others go up to five.

In most cases, the CDC defines a cluster as two or more laboratory-confirmed infections among people who likely overlapped in time and place.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and weâll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your questionâs already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The man in the photo above is Evan Cudworth. The pandemic cost him his job in the music industry. But it didnât erase his valuable work experience â over 15 years, he attended more than 1,000 concerts and other events, he estimates, and knew how to enjoy them with confidence.

Cudworth decided to put his skills to use by becoming a âparty coach.â Heâs a specific kind of life coach who helps clients relearn (or perhaps learn for the first time) how to connect with others after reorienting their lives to hide from the coronavirus. His specialty is helping people enjoy social situations without having to use alcohol or other substances as a crutch.

The lockdowns made Cudworth appreciate how vital it is to maintain relationships, and that they are worth the extra effort they sometimes require. âConnecting to people was one of the great joys of my life,â he said.

You can read more about his work in this story by Jackie Snow.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Hereâs where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Hereâs what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

Weâve answered hundreds of readersâ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.