Robert Clary, Holocaust survivor and last of the ‘Hogan’s Heroes’ stars, dies

- Share via

Robert Clary, a French-born survivor of Nazi concentration camps during World War II who played a feisty prisoner of war in the improbable 1960s hit sitcom “Hogan’s Heroes,” has died at his home in Beverly Hills.

Clary died Wednesday of natural causes, his niece, Brenda Hancock, said. He was 96.

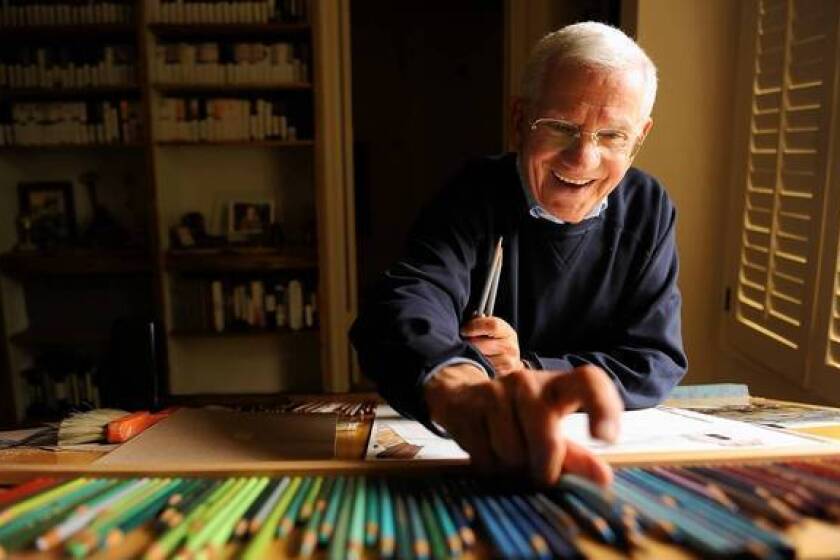

“He never let those horrors defeat him,” Hancock said of Clary’s wartime experiences as a youth. “He never let them take the joy out of his life. He tried to spread that joy to others through his singing and his dancing and his painting.”

When he recounted his life to students, Clary told them, “Don’t ever hate,” Hancock said. “He didn’t let hate overcome the beauty in this world.”

“Hogan’s Heroes,” in which Allied soldiers in a POW camp bested their clownish German overseers with espionage schemes, played the war strictly for laughs during its 1965-71 run. The 5-foot-1 Clary sported a beret and a sardonic smile as French Cpl. Louis LeBeau.

Clary was the last surviving original star of the sitcom that included Bob Crane, Richard Dawson, Larry Hovis and Ivan Dixon as the prisoners. Werner Klemperer and John Banner, who played their captors, both were European Jews who had fled Nazi persecution before the war.

Robert Clary a survivor in life and entertainment

Clary began his career as a nightclub singer and appeared on stage in musicals including “Irma La Douce” and “Cabaret.” After “Hogan’s Heroes,” Clary’s TV work included the soap operas “The Young and the Restless,” “Days of Our Lives” and “The Bold and the Beautiful.”

He considered musical theater the highlight of his career. “I loved to go to the theater at quarter of eight, put the stage makeup on and entertain,” he said in a 2014 interview.

He remained publicly silent about his wartime experience until 1980, when, Clary said, he was provoked to speak out by those who denied or sought to diminish the orchestrated effort by Nazi Germany to exterminate Jews.

A documentary about Clary’s childhood and years of horror at Nazi hands, “Robert Clary, A5714: A Memoir of Liberation,” was released in 1985. Clary was tattooed with the alphanumeric A5714 as a concentration camp prisoner.

“They write books and articles in magazines denying the Holocaust, making a mockery of the 6 million Jews — including a million and a half children — who died in the gas chambers and ovens,” he told the Associated Press in a 1985 interview.

Twelve of his immediate family members — his parents and 10 siblings — were killed under the Nazis, Clary wrote in a biography posted on his website.

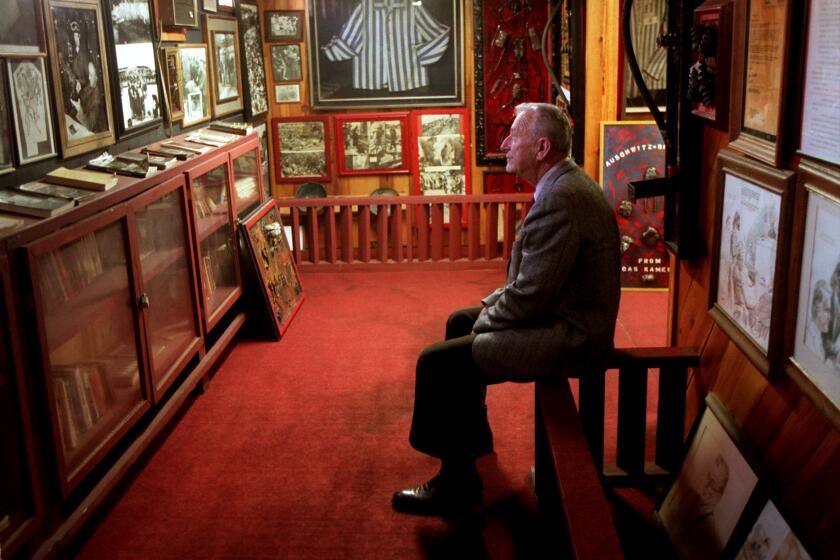

Mel Mermelstein lost his entire family in the Nazi death camps and vowed never to forget. He opened a museum and the Auschwitz Study Foundation.

In 1997, he was among dozens of Holocaust survivors whose portraits and stories were included in “The Triumphant Spirit,” a book by photographer Nick Del Calzo.

“I beg the next generation not to do what people have done for centuries — hate others because of their skin, shape of their eyes, or religious preference,” Clary said in an interview at the time.

Retired from acting, Clary remained in good health and busy with his family, friends and his painting.

The actor, born Robert Widerman in Paris in March 1926 was the youngest of 14 children. He was 16 when he and most of his family were taken by the Nazis.

In the documentary, Clary recalled a happy childhood until he and his family were forced from their Paris apartment and put into a crowded cattle car that carried them to concentration camps.

“Nobody knew where we were going,” Clary said. “We were not human beings anymore.”

After 31 months in captivity in several concentration camps, he was liberated from the Buchenwald death camp by American troops. His youth and ability to work had kept him alive, Clary said.

Returning to Paris, where he was reunited with two older sisters who had avoided the death camps, Clary worked as a singer and recorded songs that became popular in America.

After coming to the United States in 1949, he moved from club dates and recording to Broadway musicals, including “New Faces of 1952,” and then to movies. He appeared in films including 1952’s “Thief of Damascus,” “A New Kind of Love” in 1963 and “The Hindenburg” in 1975.

He didn’t feel uneasy about the comedy on “Hogan’s Heroes” despite the tragedy of his family’s devastating war experience. In Stalag 13, Hogan’s team of prisoners always outwitted the bumbling Germans.

“True, they were in a camp, but they were not treated the same as a concentration camp,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 2013. “It was a stalag. You received letters and packages.”

After the series went off the air, he remained close to the other two other actors on the series whose lives had been upended by the Nazis — German-born Klemperer, who won Emmys as the officious Col. Klink, and the Austrian-born Banner, who played the befuddled Sgt. Schultz. Both were Jews who had fled the Nazis before the outbreak of the war. “But John lost a lot of his family,” said Clary.

Clary married Natalie Cantor, the daughter of singer-actor Eddie Cantor, in 1965. She died in 1997.

A Times staff writer contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.