William Shatner is busy.

A documentary on his life, âYou Can Call Me Bill,â directed by Alexandre O. Philippe (âLynch/Ozâ), is scheduled to roll out in theaters March 22 to coincide with his 93rd birthday. He continues to host and narrate the puzzling-phenomena History series âThe UnXplained With William Shatner.â A 2022 performance at the Kennedy Center, backed by Ben Folds and the National Symphony Orchestra, is about to be released both as an album, âSo Fragile, So Blue,â and a concert film. The title song, says Shatner, âencompasses a lot of my thinking about how weâre savaging the world, and [Iâd hope] itâd be a song that people would listen to and perhaps be inspired to do something about global warming.â And on April 8, for 15 minutes before the shadow of an eclipse falls over Bloomington, Ind., Shatner will address â55, 60,000 peopleâ in the Indiana University football stadium. âSo what do you say, what do you write, what do you do? Iâm going to have to solve those problems.â

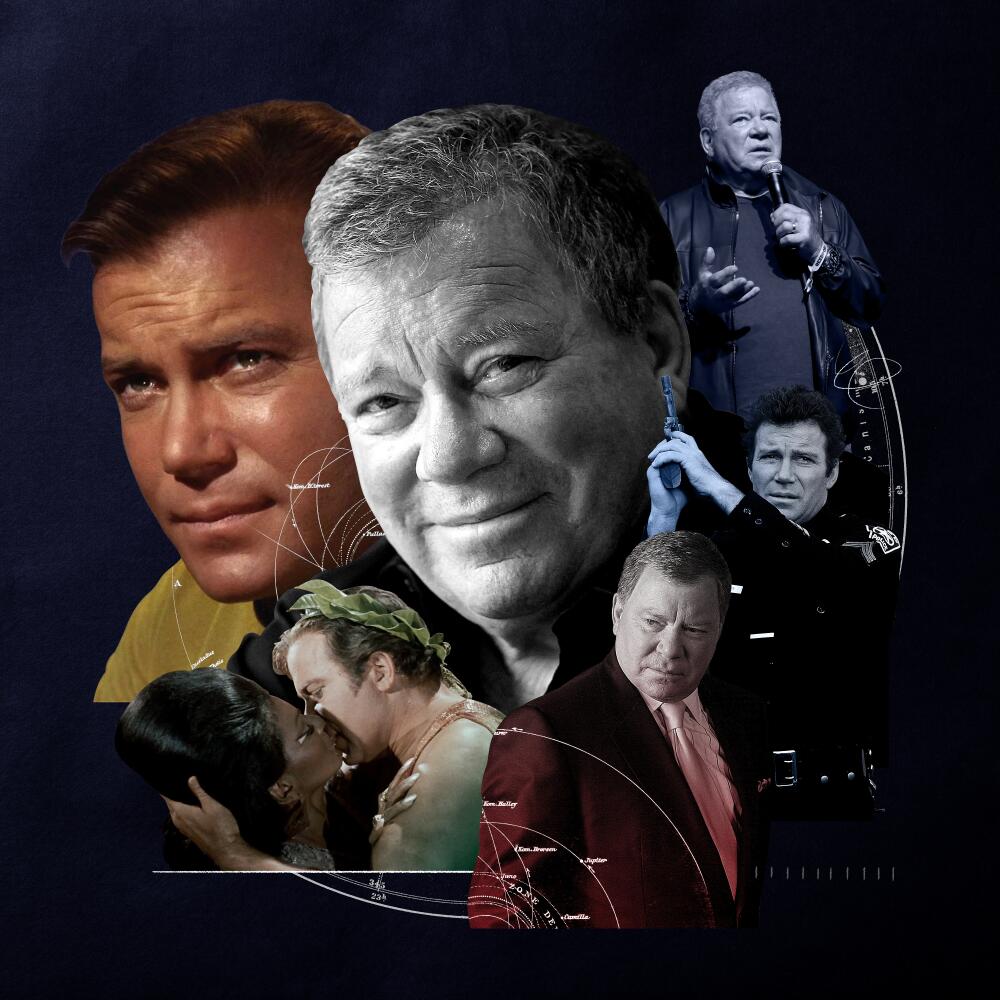

Actor, author, recording artist, equestrian, pitchman, the range of his seven-decade career â from Broadway (he won a Theatre World Award for âThe World of Suzie Wongâ in 1958), to Hollywood, Shakespeare to He-Man â has made him more than an actor in the public mind and something of a brand, or perhaps a national monument. If his role as Capt. James T. Kirk on âStar Trekâ is the fixed point from which that career extends backward and forward in time, there are things to admire in Early, Middle and Late Period Shatner alike, and the more Iâve explored the farther reaches of his work, the higher Iâve come to rate him.

There is something larger than life and at the same time very human about Shatner that makes him easy to love â and people do, sincerely, even though his singular presence can invite parody. (The word âShatneresqueâ fetches back some 40,000 hits on Google.) Nothing one learns about him â that heâs gone into space, that heâs in a horse breeders hall of fame, that he once auctioned a kidney stone for charity â seems at all surprising.

I spoke with Shatner over Zoom recently, regarding his latest performance as the villainous Keldor in the animated Netflix series âMasters of the Universe: Revolution,â and some of those farther reaches.

How do you keep your voice so young?

Wow. Where to start? Iâve had whatever the qualities of my voice are for a long time. I studied at the Stratford, Ontario, classical company when I graduated from university. And they had voice classes there, which I attended somewhat. But your voice reflects your health. Itâs a light. Listening very closely to what your voice is saying, how itâs saying. What are the gifts? I donât know. I presume Iâm using my vocal mechanism properly from all those years of training.

No regimen or voice exercises?

Used to.

You used to?

Well, I was taking singing lessons, so theyâd want you to do what is called solfeggio, to read music, and I wasnât very good at it.

Reading or singing? Youâve made a lot of recordings, but you never sing.

No. Because Iâm of the belief I canât sing. I donât know. It must be mental. I love music, I love the lyrics, I love everything about music and song, all its nuances. I love it all. I just canât do it to my satisfaction, singing. But since Iâve done a lot of classical plays, Iâm accustomed to the rhythm of the language, the onomatopoeia of the language. So mechanically I know how the voice operates. Classical theater wants you to do 10 sentences of Shakespeare on one breath. I canât do that now.

In âMasters of the Universe: Revolutionâ you play the villain with a sense of fun, as someone whoâs enjoying himself.

I think that was there in the writing â I didnât know what to do about it, an ancient animated character. How do you look for some way to do it in a new fashion, add some character to it? I didnât know how to make choices so I just sort of intuitively went along.

Any instructions from [creator] Kevin Smith?

He yelled âGreat!â a lot.

Jumping back to the beginning of your TV career, at 24 you played the title role in a 1955 production of âBilly Budd.â

I did! Canadian live television, which is where I began essentially. After Stratford I moved to Toronto and became part of that contingent. Yeah, âBilly Budd,â a wonderful play!

Basil Rathbone, who played Capt. Vere, was an elegant, distinguished talent. He was an Englishman and he spoke [posh English accent] veddy veddy. Thatâs the way he did everything, very English. So one evening as we were approaching broadcast, Basil said to me, âAre you aware weâre going to be in front of 30 million people?â I said, âYeah. [Accented burble], thatâs frightening.â And he got on the air and put his foot in a bucket, and the bucket wouldnât come off. It was like something out of Charlie Chaplin, and we spent the first act with him thumping around on a bucket and all of us trying not to laugh. You had one shot at this thing, one performance and thatâs it, goodbye. You try not to laugh, but it was very funny.

Did you ever have any fear onstage?

No. The fear onstage is not remembering words. Laurence Olivier apparently retired for five years from the stage because he went through that moment when he couldnât remember the words and frightened himself to death.

But youâre young, youâre on camera, basically the lead character â that didnât feel intimidating at all?

No. In those days, I didnât have a fear of not remembering. But you know you go through life â now, at my age, you forget why you entered the room, or your wifeâs name. Thatâs whatâs happened to me. Iâm becoming a little forgetful. That can frighten you if youâre in front of a large audience.

You went to New York in the great era of live television.

I was perhaps the most popular actor in live television on a certain year or two; I was in demand the most because I had this classical background; I was young and had some looks and there was nobody in America who had my experience of doing a play a week for two years. That appealed to a lot of people in live television.

That was followed by a period of filmed anthology shows and episodic TV, including âThe Twilight Zone,â where you starred in two of its best-remembered episodes, âNick of Timeâ and âNightmare at 20,000 Feet.â

In one year, it went from New York City live television to everybody heading to the West Coast to do film. Iâm sure historians will have an answer to why all of a sudden there was this exodus, but it happened. So everybody went west, including me, and these little shows were around; and in order to make a living, you either did a big movie, if you could get into one, that took six months to make, or you did the best you could on shows like the ones I did, in order to wait for something to come along that had more breadth to it.

Right before âStar Trek,â you played a New York City prosecutor in âFor the People,â an on-location series I like a lot.

I had speeches to make and meaningful words. It wasnât, âWhere do we go to next, who do we arrest?â It was meaningful to the character, which was great fun for the actor. But we came up against âBonanza,â and we did poorly and they canceled us.

The writers in those days were playwrights. They worked in Broadway. They were tremendously talented. And when they werenât working in the theater, they were working in live television, which was as exacting as the theater. You had to hit your mark, you had to know your lines â you had to not only know your lines but you had to be able to play with them.

In 1970, you starred as another prosecutor in the Civil War courtroom drama âThe Andersonville Trialâ for PBS, sort of a jump back to live TV. George C. Scott directed you in the role heâd played on Broadway. What was that experience like?

Iâll sum it up in one moment, and I guess itâs been unforgettable for me. So Iâm interrogating a prisoner, and Iâm saying, âWhy did you do these terrible things? [loud, accusatory] WHY DID YOU DO THESE TERRIBLE THINGS?â So after a couple of rehearsals, George comes to me, he says, âYou know, I played this part on Broadway and I played it exactly the way youâre playing it for about six months, and then the second six months I learned to try and soften the role, like it was tearing at his heart.â Saying, [softly] âWhy did you do these terrible things?â I thought, âWow, what a crowning piece of direction that is.â I became his lap dog after that.

Your best-known series were with three very different producers â Gene Roddenberry on âStar Trek,â Aaron Spelling on âT.J. Hookerâ and David E. Kelley on âBoston Legalâ â each with a distinct approach.

David Kelley is a genius. He won an Emmy for comedy and an Emmy for drama one year [for âAlly McBealâ and âThe Practiceâ], and heâd written all 48, 40 shows, whatever it was. So he would write a script and it was pretty much there when he presented it. He barely ever turned up on the set; I mean, half a dozen times over five years. But he wrote these marvelous, funny scripts. And heâs worthy of worship. He is an icon.

Aaron Spelling was so personable and so charming and had so many shows on the air that I donât think he even knew which one was on that night or not. But he was very busy. I think his charm resulted in selling a lot of shows to the networks. Gene Roddenberry had the least experience of anybody, but he must have had a fascinating talent for writing, or creating, because how âStar Trekâ came up as an idea, the fulfillment of âStar Trekâ as a drama, the things that went on in production that you wouldnât have believed was a lot to do with Gene Roddenberry. Gene was more of an everyday man. He was more the policeman, the airline pilot that he had been prior to being a writer. So there were a lot more shaded areas in Gene than anybody else.

When you got the part of Denny Crane in âBoston Legal,â did you expect to have another great role at that point in your career?

I just donât recognize these miraculous things that happen. Denny Crane, it started off with Kelley writing this character, his having been a great lawyer and now he canât remember very well â itâs not dissimilar to actors like we were talking about, not going onstage for five years. Fear. âHave I lost my talent?â I kept that in mind all the time. And the other thing that gave me great joy, his constant repetition of his name to me was like lizards flicking their tongue out â we know that their flicking their tongue out is their assessing their surroundings. So itâs a matter of âWhoâs out there? Whatâs out there?â âDenny Crane, Denny Crane, Denny Craneââ flicking his tongue out to see what the reaction was. âOh, Denny Crane, you were so wonderful!â I mean, Iâm home. âDenny Crane, werenât you the guy caught up inâ â uh oh, Iâd better leave now.

When did your relationship with horses begin? Was it on a television show?

Iâd gone on and off a horse literally within a half hour when I was 12 years old, a rental horse; and my mother said, âWhere did you learn to do that?â Because I was doing really well. I came to the mystical conclusion that in our DNA â âcause Iâve just been inducted into the [American Road Horse & Pony Assn.] Hall of Fame for breeding, breeders of American Saddlebreeds saddlebreds. You can breed for characteristics, and with some luck in three or four generations you might be able to get that characteristic youâre aiming at, or weed that one out. So I think, obviously, the same thing happens to human beings. We have in our DNA characteristics weâre not aware of. I think one of them for me was horses; somebody in my background dealt with horses a lot and then when I came upon a horse, âWow, thatâs my destiny.â I have lots of horses.

Are there things that you can get from a horse that you canât get from a human?

You can get kicked. The thing about a horse â Iâve run a charity event for the last 35 years called the Hollywood Charity Horseshow and we draw in about $500,000 a year; over the years many millions of dollars have been put into children and into veterans, who have not dissimilar problems. I saw a thalidomide baby on a horse, no arms, one leg, grasping the reins with her toes, and I decided to do a horse show right then and there, helping kids like that and veterans coming back with [disabilities]. The horses allow the kids to talk when they wouldnât talk, allowed veterans to move when they wouldnât move. The horse in its size makes somebody feel better than before they got on the horse. You can move around, you can go where you want, high up. Thatâs what horses have.

You hosted a couple of interesting interview shows, âWilliam Shatnerâs Raw Nerveâ and âWilliam Shatnerâs Brown Bag Wine Tasting,â on which your guests included people from ordinary life â a butcher, a cheese monger, a magician, a cosplayer.

Discovery, discovering what they did, discovering their personal life, how they did it, why they did it. I said, I want anybody off the street walking by and let them spend 15, 20 minutes with me. They got me a kid from the streets who sold dope, and we talked about selling dope. I said, âIâve got a horse show on this Sunday. You want to come?â He said, âYeah, can I bring my kidâ? So there was this young man who was trying to make it in this world bringing his 3-year old, 2-year-old baby to a horse show, and theyâd never seen horses.

Is it fair to say youâre a person whoâs driven by curiosity?

I think thatâs probably my best characteristic. Iâm very curious about people and how events are made. Iâm designing a watch right now. What is time? We ask yourselves that question. [Quietly] What is time? [More quietly] What is time?

Iâm designing a watch â Iâve got a watch out there now that Iâve already designed â and the concept is âWhere does time go?â Iâve been looking, and searching my brain â where does time go? And I came across a coin that doesnât look like a coin, it looks like a 3,500-year-old depiction of the skies. Itâs made of blue, I donât know what it is, azure of some kind, and gold, and thatâs going to be the face of the watch. So weâve got a watch trying to answer the question, âWhere does time go?â

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyoneâs talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.