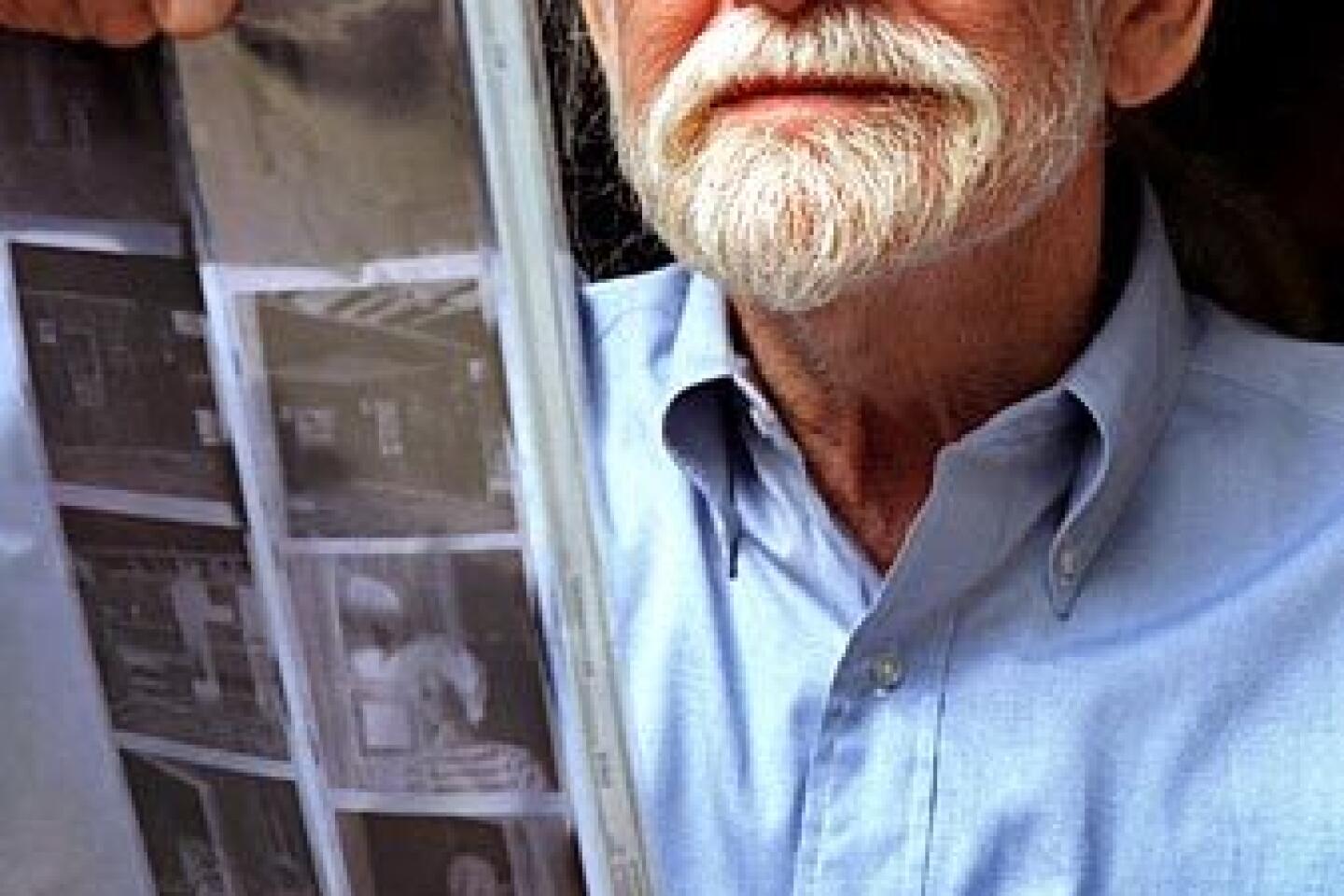

Charles Brittin dies at 82; photographer who chronicled movements of 1950s and â60s

His unblinking yet compassionate photographs in the 1950s and â60s documented Los Angelesâ beat culture and emerging art scene, the civil rights movement here and in the Deep South, the Black Panthers and antiwar protests.

Yet Charles Brittin was relatively unknown.

Sidelined by declining health beginning in the â70s, he faded from the scene as documentary photographers were first being recognized as artists, said Andrew Perchuk, deputy director of the Getty Research Institute, which holds Brittinâs photographic archive.

âHe was an absolutely critical figure in Los Angeles, because he was at the intersection of so many things that were happening,â Perchuk said. âHe also was one of the great civil and political photographers of the age.â

Brittin, who had liver and kidney transplants in the 1990s, died Sunday of pneumonia at Saint Johnâs Health Center in Santa Monica, said his lawyer, Salomon Illouz. He was 82.

One of the first subjects to fascinate Brittin as a photographer was a sleepy Venice Beach, where he took pictures âfreighted with a hushed beauty and forlorn sweetness,â according to the book âCharles Brittin: West and South,â scheduled to be published in April.

He preserved a pre-gentrified Venice that has all but vanished: Oil derricks jockey with houses and a waterway and decay creeps into the frame of a once-grand colonnade. In âBig Head, Ocean Parkâ (1957), a slightly disturbing and clownish ticket booth stands sentry at a funhouse.

A chance meeting in the 1950s with seminal beat-scene artist Wallace Berman pulled Brittin into a circle of avant-garde artists who hung out on La Cienega Boulevard at the Ferus Gallery, the influential contemporary art gallery.

Brittinâs Venice Beach shack became the groupâs second home, and he turned into the unofficial house photographer of a crowd that included actors Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper, artist John Altoon, curator Walter Hopps and poet David Meltzer.

âHe was probably the beat generation photographer,â said Craig Krull, a Santa Monica gallery owner who exhibited Brittinâs work in 1999.

âA lot of the people Charles took pictures of ended up becoming legendary figures,â Krull said. âHis photographs are more than just documents of artists and events. They are very incisive and powerful and poetic and tough.â

They also have a âromantic resonance,â because many of the elements in them are âgone forever,â Brittin said in the catalog for the 1999 show.

As the beat movement gave way to civil unrest in the 1960s, Brittin took his camera to the front lines, and his often tightly focused images were filled with raw emotion. One from a 1965 protest at the Federal Building in Los Angeles shows no faces, only body parts â the splayed legs of a black female protester being gripped by a white officer.

His political activism had its roots in his childhood in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where Charles William Brittin was born May 2, 1928.

He was the youngest of three children of a father who quit teaching and eventually ran a grocery store. âKeenly awareâ that his family had âlost status,â he came to identify with the oppressed, Brittin recalled in the catalog.

At 15, he moved to the Fairfax district in Los Angeles with his mother after his father died. The liberal student body at Fairfax High School influenced his political views, and he was soon a Marxist âon my way to changing the world,â Brittin told The Times in 1999.

He moved again, to Pomona, and after graduating from high school spent several years studying at UCLA.

In the 1950s, he married and divorced twice â and bought his first camera.

His third wife, Barbara, whom he married in 1961, shared his commitment to activism.

While donating money to the Congress of Racial Equality, the couple attended a meeting where the group posed a question: âWho is prepared to be arrested this week?â

âIn six months, Barbara was teaching techniques of nonviolent resistance, and I was taking political photographs,â Brittin said in The Times in 1999.

He made dramatic black-and-white prints of protests in Southern California and in Mississippi and Louisiana, where he and his wife spent three months in 1965. By the end of the â60s, Brittin was chronicling the Black Panther movement.

âHe had an absolutely phenomenal sense of composition,â Perchuk said. âEven when he was in the midst of action at a demonstration, he found a perfect way to frame it that conveyed very precisely what was going on.â

From 1963 to 1970, Brittin worked as the official photographer in the Los Angeles studio of noted midcentury designers Charles and Ray Eames.

Throughout his career, he also photographed still lifes composed of unlike objects such as a womanâs high-heeled feet with an iron-link chain or doll heads.

Brittinâs photographs will be featured in âPacific Standard Time,â an exhibit of collected works scheduled to open Oct. 1 at the Getty Center.

When a slowly progressing condition caused his health to deteriorate, he put his cameras away until the 1990s, when his health improved after his transplants.

With Barbara, he lived for decades in Santa Monica Canyon. She died at 74 in 2003. He has no immediate survivors.

Before the civil rights movement, he did not have âthe confidence to exploit the opportunities that came my way,â Brittin said in the 1999 catalog. âThen, something more important than my personal comfort was at stake, so I was able to be aggressive and do things that seemed unnatural to me.â

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.