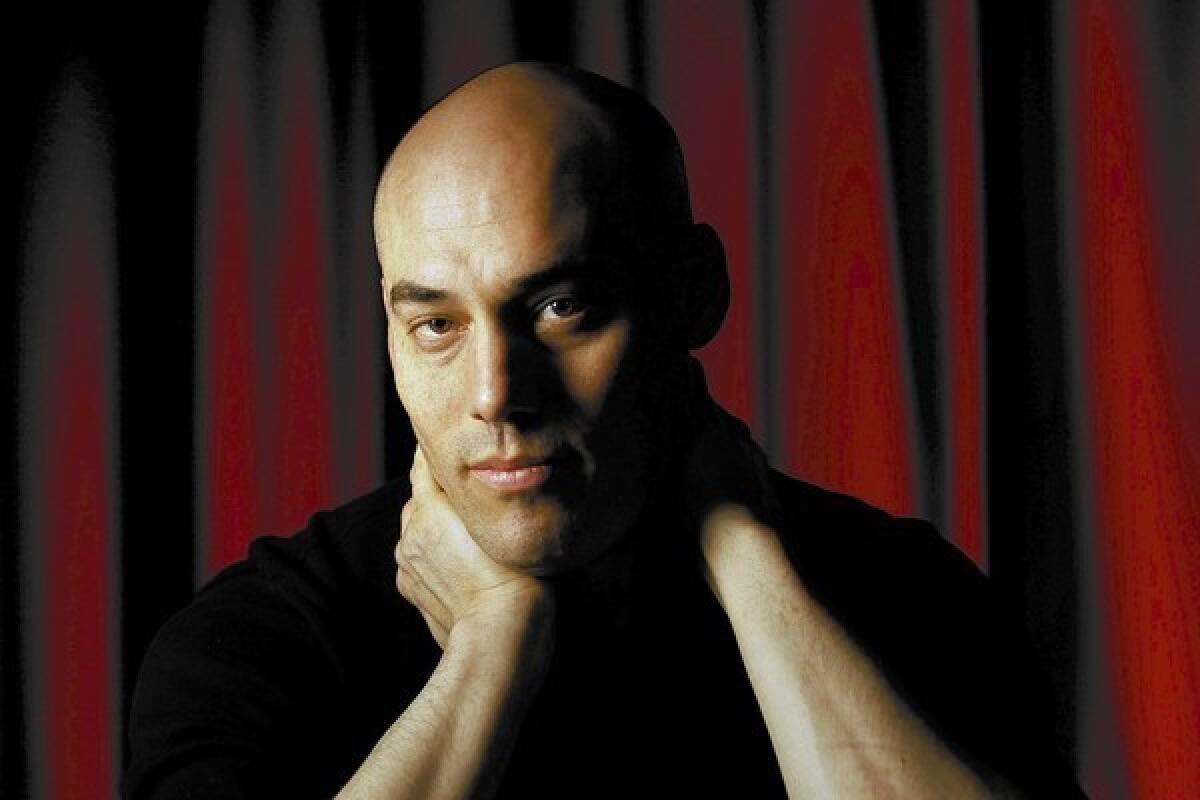

Joshua Oppenheimer on ‘The Act of Killing,’ reconciliation

- Share via

Joshua Oppenheimer’s provocative documentary “The Act of Killing” is shocking for all the right reasons. The director took nearly a decade to film the Oscar-nominated story about mass murder that showcases the killers of more than 1 million Indonesians in the aftermath of the overthrow of the government in 1965.

While the leader of that military coup is no longer in power, his people remained in charge, having executed anyone they wanted — labor union members, leftists, intellectuals and the like — along the way by labeling them communists.

Because the film’s executioners had a passion for movies, Oppenheimer asked them to reenact their murders on camera as a cinematic production, creating a complex treatise on genocide, cinema, art and the dark side of human nature.

PHOTOS: Oscars 2014 top nominees | Nominee reactions | Snubs and surprises

How or when did you learn about the 1965 mass Indonesian killings? Did you know about them prior to arriving in Indonesia?

I learned of the killings only when I went to Indonesia in 2001 and 2002 to help plantation workers make a film documenting their struggle to organize a union on a Belgian-owned oil plantation complex. They were fearful to organize because they had this memory of their parents and grandparents being killed in 1965, and they suggested I make a film about why they were afraid — because they lived with the perpetrators who were still in positions of power all over the country.

When the army wanted survivors to no longer participate in the filming, the workers suggested I film the local perpetrators, so I did, with a little trepidation at first. But I found to my horror that every single one of them was open, describing boastfully the grisly details of the killings, often with smiles on their faces, in front of their wives, children, even their little grandchildren. I then spent two years filming every perpetrator I could find, working my way from death squad to death squad up the chain of command to the city of Medan, when I met with [Anwar Congo, one of the central figures in the film].

How did you get these sorts of people to trust you? Gangsters, killers and thugs are not normally trusting people, especially of a foreigner with a camera.

Oscars 2014: Complete list of nominees | Play-at-home ballot

I think because they remain in power. Unlike the Nazis, they were never forcibly removed and therefore never forced to acknowledge what they did was wrong. Also, unlike the Holocaust, at the time of the killings they knew that the West was supporting what they did. And if you know also that your own government supports your boasting about what you did so you can be feared proxies of the state, you might not be so wary of speaking with foreigners. It was not that I pretended to be supportive. When there was a safe space, I let my feelings be known. But I found people were open immediately. The method is not a trick to get them to open up; it’s a response to their openness and a way of knowing why they’re so boastful.

Anwar Congo was the 41st perpetrator you interviewed. What was it about him that made you know he was the one to focus on to unravel the story?

With Anwar, I could see his pain. The very first day I met him he takes me to the roof where he killed and he did something almost more boastful than any of the other perpetrators, which was to dance on the spot where he killed hundreds of people. Yet, there at the start he said he was drinking, taking all these drugs to forget his pain and his trauma; it was right there in the beginning, and after five years and 1,200 hours of film later, we see it at the end as he walks out of the office.

I saw when I got to Anwar that all this boasting, which I’d spent two years filming, might not be a sign of pride but may be a sign that these men know what they’ve done is wrong and are desperately trying to convince themselves otherwise with threats and imposing that view on society. These are the men who have the awful memories of killing people, strangling them, cutting off their heads; their trauma was not at a distance. Humans are unlike any other species. We kill our own with gusto, but I believe it’s still a trauma.

PHOTOS: 14 completely awkward Oscar moments

Why is it a documentary that tells this hidden story — not a history book, investigative newspaper story — and what might this say about the changing role of documentary film today?

We all identify with the people we see, and in a good documentary we are not just reading an account of the world, we’re seeing and hearing our world. The film’s an observational documentary of the imagination as well: What happens to a society when the killers have won? We can see and hear the answer to that. It also speaks to the identification and immersion that cinema can offer as a mirror in a particularly powerful way. It’s also true that Indonesian youth have a connective voice, and freedom to type and communicate on the Internet, and talk to each other and not be as afraid.

So when we’re talking about the concept of winners and who gets to say what’s a crime and what’s patriotic necessity, this story really is the Native American and the cavalry, right? Something cinema had a great part in distorting to Americans and outward to the world …

Exactly, and we can watch in horror as Anwar and his men make a cowboy scene [in the film] into genocide, but we have to remember that the whole [western] genre exists because of genocide, to celebrate and justify genocide. It’s the genre’s whole raison d’être.

The film’s been shown thousands of times in hundreds of cities in Indonesia. Is there a particular story you find moving as a result of Indonesians coming together to discuss their traumatic hidden history?

There was a screening in a village in central Java, students of a religious organization that participated in the killings in 1965, and they held a screening at a mass grave with survivors. Now I would never suggest holding a screening of this film at a mass grave, but they wanted to. Every year survivors would want to go to this particular grave during Ramadan to pay their respects to their dead, and the Pancasila Youth [a right-wing paramilitary Indonesian group] would physically stop and sometimes attack them.

But they held this screening at the grave, and ever since, both survivors and the children of perpetrators have gone to pay respects to the dead, together. It’s that kind of opening of a space for reconciliation — we don’t want our country to be like this, like what you see in the film — that has been the most wonderful response.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.