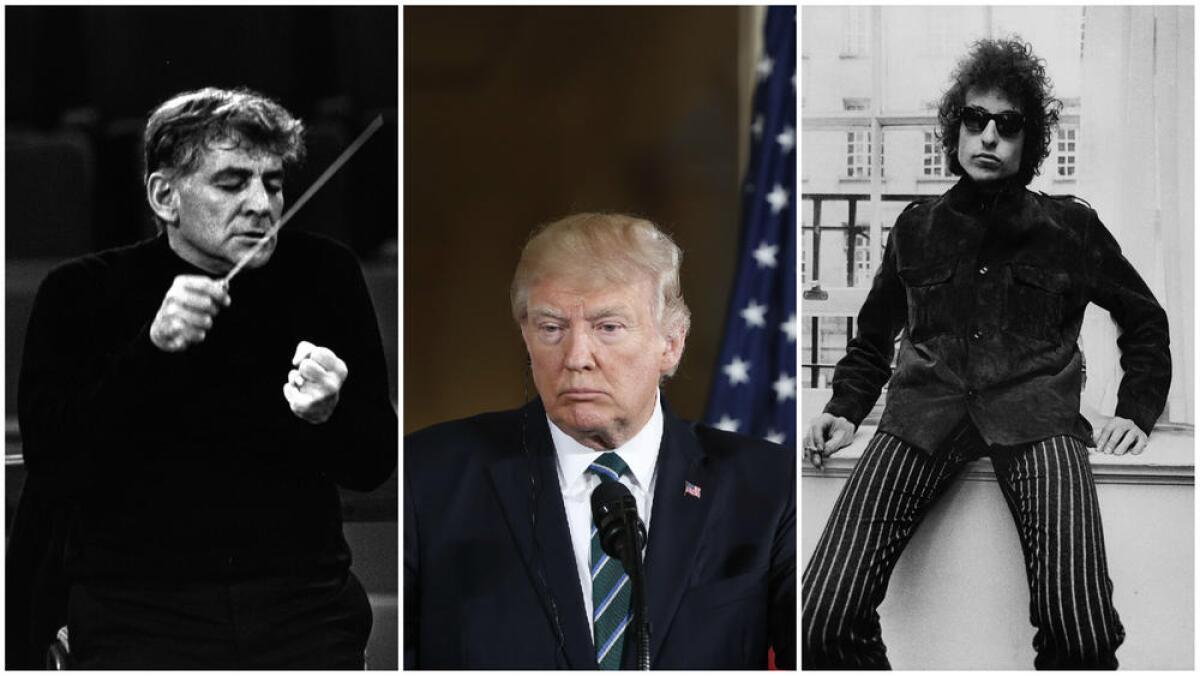

L.A. without the NEA: What does that look like? If the National Endowment for the Arts were to lose its funding, as has been proposed by President Trump, would many people notice?

Would you?

The Times is setting out to answer that question in this series that looks at the NEA through the lens of one city and its environs, where the proposed cuts have the potential to affect gargantuan arts institutions and grass-roots programs alike.

For a giant like the L.A. Phil, how does the NEA factor into the big picture?

The Los Angeles Philharmonic is hardly a shoestring operation, with its $255-million endowment and an annual budget of $120 million for the 2015-16 season. The 106-member orchestra led by Gustavo Dudamel is considered one of the most preeminent in the world, not to mention the most financially secure in the country.

So why, then, with its ticket sales and network of donors, would the L.A. Phil seek funding from the National Endowment for the Arts?

Hereâs one answer: to push the art of music forward. For its 2016-17 season, the L.A. Phil received two NEA grants, one of $90,000 for its in/Sight program pairing video art with orchestral and choral music â one way the orchestra has been drawing new audiences to Walt Disney Concert Hall. The funds went toward artist fees, marketing and production costs for the video art and pre-performance talks for four concerts, the L.A. Phil said. The other NEA grant, for $20,000, went toward the Inside the Music program led by journalist Brian Lauritzen, offering four videos, talks and an online game to round out the concert-going experience.

Another reason why such a large organization bothers with relatively small NEA grants? In a word: partnerships.

NEA study explains financial effect of the arts nationally â and Californiaâs huge cultural economy

Data released Wednesday by the National Endowment for the Arts, in a joint effort with the Bureau of Economic Analysis, offer an argument for keeping arts funding alive at a time when the Trump administration seeks to eliminate the NEA altogether.

The data, which look at the economic role of the arts at the federal level, show that the arts and cultural sector contributed nearly $730 billion to the U.S. economy in 2014, the year for which the agencies evaluated data. That is roughly 4.2% of the U.S. economy for that year. (The NEAâs annual budget, as a point of comparison, is $148 million.)

California rose to the top in a number of key areas in state-by-state comparisons analyzed in the Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account report (or ACPSA).

âWhen I read your inspiring column this morning, I felt that it could be deemed todayâs spiritual readingâ

The Timesâ series âL.A. Without the NEA,â about how the National Endowment for the Arts works at the community level and what the local cultural landscape might look like without the agency, has been generating dozens and dozens (and dozens) of reader responses.

One piece that clearly struck a chord was by theater critic Charles McNulty, who wrote about how the stage has shaped his life. âI was raised Catholic, but my adopted church is the one in which the scripture is by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, Shakespeare and Molière, Ibsen, Chekhov and Beckett and a dozen other playwrights who widen the frame of our understanding by presenting us with characters who are in collision with one another, with society and with the very nature of existence itself,â McNulty wrote.

Among those touched by the piece was Sister Rita Yeasted of La Roche College in Pittsburgh. She writes:

I have been a nun for over 50 years, most of them teaching English. I currently teach at a small, liberal arts college in Pittsburgh, and while I teach everything from freshman comp to senior seminar, drama has always been my passion.

The great joy of my life is to take students to see a play, especially when they have never experienced live theater.

When I read your inspiring column this morning, I felt that it could be deemed todayâs spiritual reading. I am horrified at the thought that once again funding for the NEH and NEA is on the line. The proposed budget to expand our military and cut health care and Meals on Wheels is immoral, but I truly believe that to deprive citizens of art and the humanities will cause another kind of death. I have devoted my life to helping students to become more human, and while I am a new digital subscriber to your newspaper, your column today more than justified the expense of a subscription.

For the record, you may consider yourself a âformer Catholic,â but the values taught [to] you at a younger age are still manifest. Obviously, my faith inspires my life and teaching, but I believe that your advocacy for embracing our humanity, especially in literature and drama, reminds all your readers today that losing the arts is losing our humanity; indeed, it is, as you say so eloquently, losing our souls. Thank you for allowing my friends and me to reflect on why we invest time and money in theater tickets. Letâs both hope that wiser heads and hearts will fight vigorously to defend government support of the arts. Keep up the good work.

Bringing respect to the craft artist: How one small museum does it, page by page

Giving lesser-known artists visibility is key to the mission of the Craft and Folk Art Museum, says Executive Director Suzanne Isken, whose institution has an annual operating budget of about $730,000 â less than what some Hollywood stars make for a few daysâ work.

Which is why a $25,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts has been so crucial for the L.A. museum to stage its current exhibition, âChapters: Book Arts in Southern California.â

The exhibition features more than 100 altered and sculptural books, zines and artist-driven publications made since the 1960s. And a line-item breakdown of how the $25,000 and matching grant money were spent offers a window into the pricey but necessary minutiae associated with a museum exhibition â costs that the public may not consider.

Shipping art to and from the museum, for example, cost $800. Security for the show cost $1,200. Postcard printing and mailing cost $150. Three advertising spots on a local NPR station totaled $1,500. Lighting and painting supplies were $1,140. Insurance for the show was $1,200. The most expensive item on the list: $8,000 for labels and wall text fabrication for the exhibition. Artist fees for all commissioned work totaled only $6,000.

Self Help Graphics project empowers day laborers through art

Come May, the community arts center Self Help Graphics will traverse the Eastside of Los Angeles staging pop-up workshops. Its target students? Local day laborers and street vendors who might not otherwise have time for art classes.

The project, JornARTleros, is the brainchild of the 44-year-old nonprofit in partnership with Leadership for Urban Renewal Network, the Boyle Heights-based economic development organization known as LURN, and the L.A.-based National Day Laborer Organizing Network. The project was significantly funded with a $20,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Making music an instrument for change: HOLA points kids toward a better path

It is one of the most densely populated areas west of the Mississippi. The poverty rate is over 35%, and more than a quarter of all households earn less than $15,000 per year. At least 30 gangs roam the streets, recruiting children as young as 9. The high school graduation rate is around 50%.

Thatâs the state of affairs in Westlake, Pico Union and Koreatown, according to the organization Heart of Los Angeles. The group reaches more than 2,000 kids in those neighborhoods every year through after-school arts and athletics programs, but its crowning achievement is its partnership with the Los Angeles Philharmonic: Youth Orchestra Los Angeles at Heart of Los Angeles, or YOLA at HOLA.

When Ben Feldman and Mamie Gummer take the stage, think of the NEA

Ask what it takes to create new theater at South Coast Repertory, and you will get an interesting answer. It takes seven playwrights, six directors and five dramaturgs. Forty-four actors. Seven interns. Design teams. Technical crews. Administrative support.

And more.

Thatâs whatâs required just to stage this yearâs Pacific Playwrights Festival, where South Coast Rep will present readings and staged productions of seven new plays. The National Endowment for the Arts provided $50,000 this year to partially cover participantsâ pay as well as travel and lodging expenses.

I think in many ways itâs the symbolic value of the NEA that moves me the most. ... Having a national institution sends an unmistakable signal that we, as a country, believe in the importance of the arts. ... The arts are not by and for a group of elite artists out there somewhere; theyâre for all of us. As such, theyâre not a luxury; theyâre an essential part of any healthy, dynamic society.â

— Julia Cho, playwright

Independent Shakespeare Company makes poetry in the park

To borrow a line from Sonnet 18, summerâs lease hath all too short a date when the Independent Shakespeare Company wraps up its annual free performances in Griffith Park each September.

The nonprofit has been staging shows in L.A. parks for 14 years, and now draws an audience of more than 50,000 for 49 performances presented over 11 weeks, beginning in late June.

Free admission for all: Grand Performances makes it happen

Grand Performances has staged free summer shows at California Plaza in downtown Los Angeles since 1987. The organization has received a total of $576,125 in the form of 19 grants from the National Endowment for the Arts since 2000. Rather than use that money to commission new work, Grand Performances usually produces existing work â 35 to 50 performances of music, dance, theater, spoken word and more every year.

âFirst and foremost, the NEAâs value is that it has helped democratize access to the arts,â said Grand Performances Executive Director Michael Alexander.

NEA helps the Autry Museum provide a rare platform for Native American playwrights

Giving the descendants of indigenous people an artistic platform is the goal of Native Voices at the Autry Museum of the American West, which for more than 18 years has housed the countryâs only Equity theater company dedicated solely to producing new works by Native American, Alaska Native and First Nations playwrights.

How one little-known program saves museums millions

When the Palm Springs Art Museum was arranging âWomen of Abstract Expressionism,â all the typical special exhibition concerns arose: How to tell the story of 12 largely unrecognized female artists? How best to configure and install the works? Myriad logistical issues came with the shipping of 50 major paintings from lenders around the United States.

But one question didnât keep the museumâs director of exhibitions and collections management, Alicia Thomas, up at night: How to insure the pieces against theft or damage?

Embattled and emboldened: Arts and culture in the age of Trump

Some might say that as a drama critic, my job is to give readers my verdict on theater productions and that I should stick to Shakespeare and show tunes and shut up about the state of the world. But the arts hold a mirror up to nature, which includes politics, and playwrights dating back to 5th century BC Athens have understood the uniquely public aspect of their art form. The stage is one of the few places left in our democracy where citizens turn off their phones to collectively confront the thorniest issues of the day.

It is imperative that those of us fortunate enough to earn a living in the embattled arts and culture sector of the ruthless U.S. economy do more than advocate for our professional survival. Yes, the arts create jobs. But even more important, they support the human infrastructure of our society. Thereâs more at stake in the fight to preserve the NEA and the NEH than the next âHamilton.â Our souls, which is to say our fundamental values, are on the line.

Lula Washingtonâs aim is to lift up lives through dance

In the 1970s Lula Washington was denied admission to study dance at UCLA based on her age, 22, which the university deemed too advanced for the program. Washington, who was married and had a small child at the time, eventually was admitted and went on to found the universityâs Black Dance Assn.

In 1983 Washington established a dance school to provide low-cost and free dance lessons to kids in low-income neighborhoods. More than 45,000 inner-city children have attended the school.

Cornerstone brings theater to the theater-less

Cornerstone Theater Company in the Arts District of downtown Los Angeles has carved a niche through its multiyear âplay cyclesâ examining timely themes. The Watts Cycle sought to sow the seeds of camaraderie between African American and Latino residents of a South L.A. neighborhood. The Justice Cycle explored the effects of law enforcement on various communities, and the Faith-Based Cycle examined the role of religion in modern life, including LGBTQ and Catholic communities.

Each of these cycles has received grants of $30,000 to $60,000 in years past from the National Endowment for the Arts. The current Hunger Cycle received $30,000 for âMagic Fruit (The Hunger Bridge Show).â

Diverting kids away from crime and toward something positive

When President Trumpâs budget proposal landed last month, one of our first calls went to Theatre of Hearts, which has received seed money from the National Endowment for the Arts on and off since 2004. This year, it was awarded $15,000 to support its Literacy Alive Mural Program, which will bring professional artists to the Central Juvenile Hall School near downtown L.A. to mentor students in creative writing and visual arts.

What does the NEAâs $148-million budget buy? 7,789,473 taco bowls, but not even one mile of the 405 Freeway

What exactly can one do with $148 million â besides fund thousands of arts programs in communities large and small across the nation? When it comes to big, infrastructure-y photo-op stuff â like expanding a freeway or building a border wall â not all that much. It wonât even get you an entire Picasso at auction.

The money will, however, buy you a whole lot of taco bowls.

If Trump thinks artists are a problem now, just wait: Why history tells us the fight isnât over

If President Trump thinks heâs got a problem with artists and academics now, just wait. Incensed artists and college professors are not to be messed with. No one can stir up revolutionary furor like artists and educators. Trump is old enough to remember how effective culture and colleges were in turning America against the Vietnam War and ultimately bringing down a president.

How would the death of the NEA affect your community? California can cite 162 ways

Big-name art projects are only a small part of what the NEA funds. The proposed elimination of the NEA and the National Endowment for the Humanities, announced in March in a 2018 budget blueprint from the Trump administration, would hit closer to home.

Murals by low-income students at probation centers. New works by Native American, Alaska Native and First Nations playwrights. Art outreach for the homeless of skid row and South L.A. These programs and organizations are among the 162 in California listed in a recent NEA grant announcement.

The NEA works. Why does Trump want to destroy it?

Yet another fight is shaping up over elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts, which on Thursday the Trump administration announced as part of its first federal budget proposal. The National Endowment for the Humanities, Institute of Museum and Library Services and the Corp. for Public Broadcasting, a chief revenue source for PBS and National Public Radio, would also get the ax.

How many times has this battle already been fought? Welcome to âGroundhog Day.â