If Trump thinks artists are a problem now, just wait: Why history tells us the fight ain’t over

- Share via

It is all too easy to follow the dollar when considering the White House budget proposal to eliminate our national endowments for the arts and humanities. As has been pointed out everywhere, the money is negligible. Were the president to move his wife and son to the White House and spend his weekends in Washington or at Camp David, the public would probably save more in security costs for Trump Tower and Mar-a-Lago than the $300 million or so the government spends on the NEA and NEH.

The arguments that even this pittance (a fraction of what France, Germany and Russia provide their citizens) has significant financial returns and generates jobs have long fallen on deaf ears. Indeed, does that extra money spent on security for the president go more for overtime than new jobs, especially considering the current desire to shrink government?

The administration simply sees the arts and humanities, like the press, as a threat. And it’s not wrong. The arts community overwhelmingly seems to disapprove of Trump, as does academia. So why not defang your enemy with the purse strings? Here’s why.

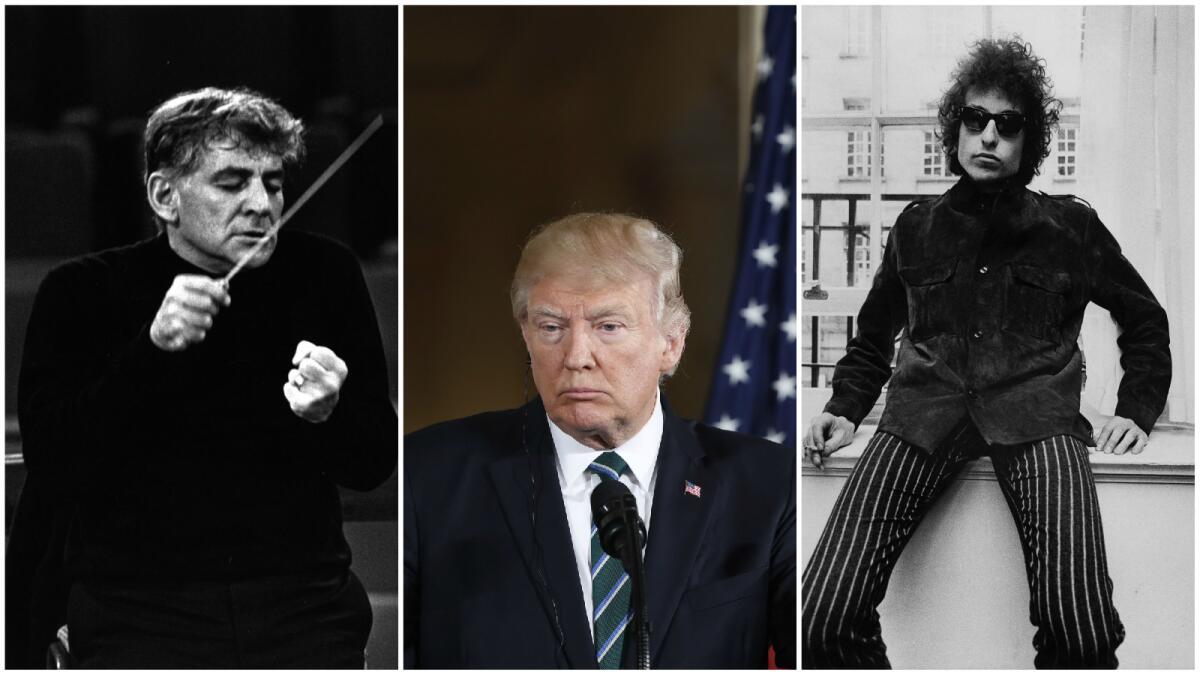

If President Trump thinks he’s got a problem with artists and academics now, just wait. Incensed artists and college professors are not to be messed with. No one can stir up revolutionary furor like artists and educators. Trump is old enough to remember how effective culture and colleges were in turning America against the Vietnam War and ultimately bringing down a president. Pop culture had a lot to do with it, of course, and that pop culture has become legitimized thanks to Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for literature.

America’s finest writers and visual artists also were a crucial part of the movement, as was classical music. Leonard Bernstein was a major force. His “Mass,” which opened D.C.’s Kennedy Center in 1971, was a revelation to officials in Washington of how dissent in America could be interpreted as a spiritual journey. His Concert for Peace, a nationally broadcast performance of Haydn’s “Mass in the Time of War” at the Washington National Cathedral at the start of 1973, validated antiwar protests to the thinking general public. Bernstein set the stage, in ways yet to be fully appreciated, for creating an atmosphere in which the public was ready to impeach a president.

Let’s not forget, as well, how university campuses were both a breeding ground for revolutionary spirit and a hallowed sanctuary for young rebels. Colleges did not then, as now, teach courses in the Beatles; the students, instead, lived John Lennon’s Leninist lessons.

The very fact that President Trump is making the redlining of the NEA and NEH appear personal (could Sylvester Stallone’s turning down of Trump’s invitation to head the NEA have something to do with it?) is likely to incense the art and academic worlds that much more. Outrage will spill into the streets with more protests.

Not only are artists and academics, as a class, the world’s most persuasive kvetchers, they are also our moral compass. They are more ready than most of us to be arrested, as we saw in the 1960s. There is nothing to stir a student into action like seeing a revered professor being arrested for standing up for high ideals. There is nothing like being behind bars to inspire a righteous protest poem or song or drawing.

Oh, yes, many will have more time for protest because they won’t be spending all those soul-numbing hours writing applications, in which they often have to compromise themselves to meet bureaucratic standards. One set of handcuffs might be applied, but another set will come off.

No one knows this better than the leader Trump seems to admire the most, Vladimir Putin. Although he may be highly selective in what artistic institutions he supports, Russia’s president is unique among world leaders in the lengths he goes to promote his nation’s culture. The Mariinsky in St. Petersburg is a particular favorite, so he built it a second opera house.

If Trump visits Putin, he can expect to be taken to the Mariinsky, the Hermitage and the Bolshoi. Putin may not be up to any good, but he understands the value of using culture to create a national identity that helps keep a vast country and vastly diverse population together.

I wouldn’t be surprised, in fact, if Putin’s arguments that Crimea is too much a part of the Russian soul had more effect on his public’s overwhelming support of the occupation than did economic or strategic arguments. Such Russian writers as Pushkin, Chekov, Tolstoy, Nabokov and Mandelstam went there to write. Most of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, played just last week by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Thursday by the St. Petersburg Philharmonic at Valley Performing Arts Center in Northridge, was written in Crimea. All Putin had to do was remind Russians of that.

Let me leave you with a what-if. What if Trump, knowing that his predecessor paid little attention to the arts beyond lip service, decided to woo artists by vastly expanding the NEA rather than demolishing it? What if he decided to show up Obama and went so far as to create a Cabinet post for culture, as many called upon Obama to do? A good negotiator might see that as good way to sweeten the pot for Sly.

Trump wouldn’t win over his opponents. They have too much against him, and most independent-minded artists and academics are not easily corrupted. A presidential ego wouldn’t get a break. Still, the tone would be different.

Artists now distracted by the urge to make protest art could go back to other things. Teachers would need not feel compelled to relate whatever their subject is to politics.

Even music critics could go back to music.

ALSO

The NEA works. Why does Trump want to destroy it?

What is the National Endowment for the Arts and what would we lose without it?

How would the death of the NEA affect your community? California can cite hundreds of ways

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.