As The Times’ pop critic, I saw some 150 concerts at the Bowl. This one topped them all

- Share via

Janis Joplin raced onstage at the Hollywood Bowl on a September night in 1969 with the urgency of someone fleeing a burning building, her long reddish hair blowing in the wind. She slowed only to grab a microphone from its stand before resuming her dash to the lip of the stage to be as close as possible to the fans. In the most gripping moment, she later screamed (sang is too tame a word), “Come on, come on, come on, come on and take it / take another little piece of my heart now, baby.”

For 40 minutes Joplin was electrifying, and the experience was all the more striking because of the setting. The Bowl, which celebrates its 100th birthday this summer, had been built with the loftiest of intentions — the elegant summer home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, the gorgeous gathering spot for the annual Easter sunrise services and a showcase for highly respected stars of Broadway, pop and jazz.

On paper, Joplin and the Bowl were a mismatch.

The 26-year-old ragged-voiced singer from Port Arthur, Texas, who was known to take swigs of Southern Comfort between songs, was associated with sweaty blues clubs and rowdy rock venues.

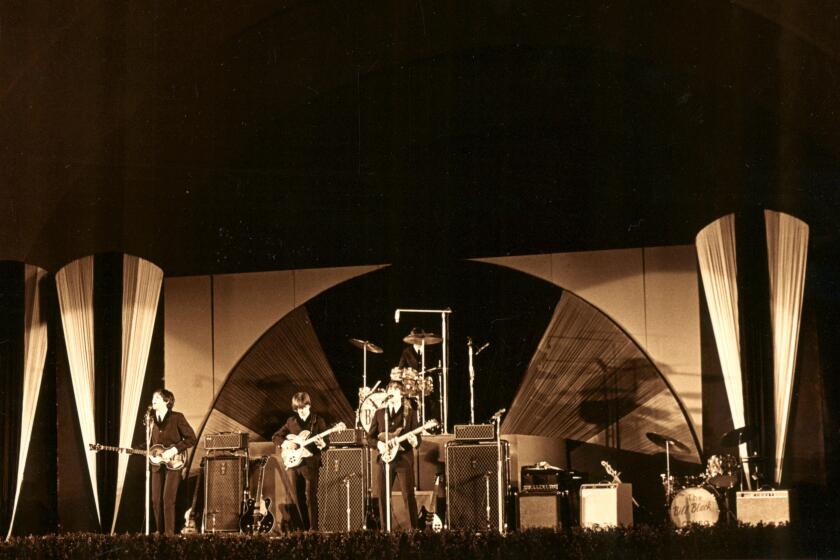

The amphitheater had already opened its doors to a few rock figures, including the Beatles and Bob Dylan, but she was a step into the unknown — a female rocker with a reputation that bordered on out-of-control. I didn’t see her performance in 1968 at the Bowl, but things went smoothly enough for her to be invited back.

Yet concern about Joplin’s erratic behavior heightened in March of 1969 when Rolling Stone compared Janis with another vulnerable and reckless star. A cover headline asked: “The Judy Garland of Rock?” The question became more unnerving three months later when Garland, herself a Bowl headliner in 1961, died of what was ruled an accidental drug overdose in London. Her death added an uneasy theme to Joplin’s return to the Bowl. (Joplin, too, would die from an accidental overdose, at a Hollywood motel less than a mile from the Bowl, on Oct. 4, 1970.)

‘Maybe I won’t last as long as other singers,’ Janis Joplin once said in an interview. ‘But I think you can destroy your now worrying about tomorrow.’

But the Joplin/Bowl pairing was a triumph on both sides — one that would stand as the most memorable of the some 150 shows I saw there over my 36 years as the pop music critic of The Times, a list highlighted by such other giant talents as Dylan, Johnny Cash, Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney, Elton John, Prince and Radiohead.

During an interview in her dressing room earlier the day of the concert, Joplin was not reassuring. Clutching a whiskey bottle as she sprawled on a sofa, she went through a series of draining complaints about endless fights with business people and musicians as well as having writers continually asking her about where all the pain in her voice came from.

The only time she sat up was when I brought up the Garland comparisons.

“That’s what I mean about writers,” she said. “People seem to have a high sense of drama about me. Maybe they can enjoy my music more if they think I’m destroying myself. Sure, I could take better care of myself. I suppose I could eat organic foods, get eight hours of sleep every night, stop smoking — things like that. Maybe it would add a couple of years to my life. But what the hell?”

For the next hour, longer than she would be onstage, Joplin addressed the reasons behind the pain in her voice — her years as the ugly duckling who was treated as an outcast in high school — and how music was the one thing that she could count on. “I live for that hour onstage. It’s more excitement than you expect in a lifetime. It’s a rush.”

From my third-row seat that night, Joplin was so joyful at times in the blaze of audience affection that she broke into giggles. It was endearing.

Though most of her songs were supercharged blues numbers, she changed the pace with a softer song that was familiar to older Bowl regulars, the few who were spread throughout the mostly young, capacity audience.

George Gershwin composed “Summertime” in 1934, with lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin, for the opera “Porgy and Bess,” one of the monumental pieces in American music. The song felt out of place alongside the aggressive “Piece of My Heart” on “Cheap Thrills,“ her 1968 album with Big Brother and the Holding Company, but it was absorbing live as Joplin’s vocal achingly expressed the deep longing for comfort promised in the song. Together, “Piece of My Heart” and “Summertime” represented the Rosebud of Joplin’s journey.

As I remember it, Joplin left the stage far differently than she arrived, frequently pausing to wave to the audience, trying to make the set last just a bit longer. But her time was up. Concerts were shorter in those days.

When I spoke with her a few months later, she was more upbeat. She was looking forward to recording a new song that would again expand her musical range, Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” — an uplifting, country-flavored sing-along about recapturing faded good times.

She spoke fondly of her two Bowl appearances, calling them among her proudest moments, having stood in the footsteps of such figures as Billie Holiday (who had the first hit recording of “Summertime” in 1936) and Garland.

“The old folks back home still don’t accept me,” said Joplin. “They don’t see the rock joints as any big deal, but the Bowl is different. I wish they could have seen me there. The Bowl is a classy joint.”

More Coverage: Hollywood Bowl

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.