‘I have to look at flat horizons’: Joan Didion on her apocalyptic California optimism

- Share via

I had known Joan Didion casually for many years when I asked her to join other artistic icons, including Frank Gehry, David Hockney and Clint Eastwood, in chatting with me for my book, “State of the Arts: California Artists Talk About Their Work” (2000). What was it, I wanted to know, that had lured so many of the country’s most creative people to settle in a state well known for fires, floods, earthquakes and other, more psychological disasters?

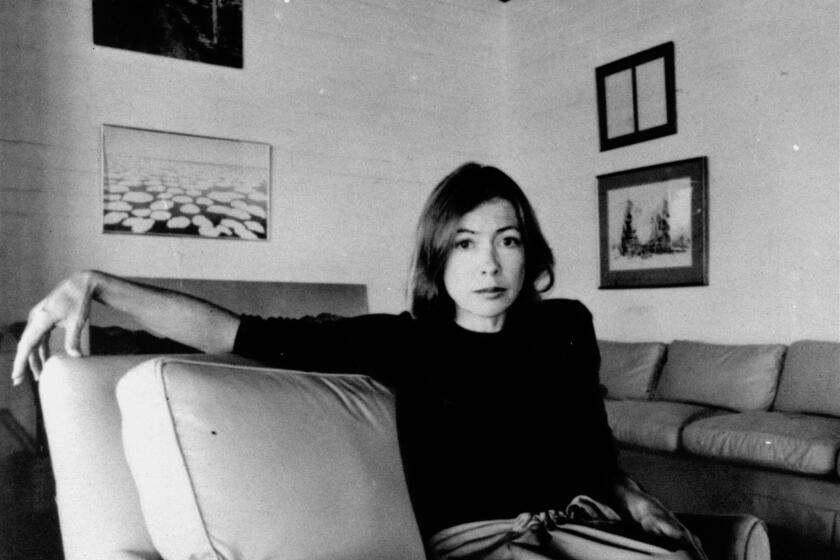

It was something she, a native Californian, was eager to talk about. And so one day near the end of the 20th century, I sat in her New York living room for several hours as she talked about where she was from. But first she urged me to have a look around, pointing out the calm of the room’s pastel-colored walls and paintings as she unspooled the competing themes of California — possibility and disaster — in the same strikingly balanced, nearly perfect sentences that distinguished her writing.

Long considered the state’s chronicler of record, she once described it as the place “we run out of continent.” That’s where Joan Didion, who died this week at 87, began her story — with the moment her ancestors arrived at the end of the land.

—Barbara Isenberg

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

My mother’s family came to California in the 1840s and my father’s family in 1852. They came looking for richer land. There wasn’t anything glamorous or dramatic. They weren’t propelled by some mission. I think it was something to do.

I wanted to be a writer, and my mother encouraged me. My father didn’t discourage me. We just didn’t have that discussion. I taught myself to type by typing out other people’s fiction. I did a lot of Hemingway. You found out how the sentences work. I got very fast as a two-finger typist by typing out Hemingway’s short story, “The Hills Like White Elephants” and the whole beginning of “A Farewell to Arms.”

I went to Berkeley in the spring of 1953. I was the editor of the literary magazine and took what few writing classes there were. Then I put off writing fiction because it was so clear that everybody had already done it. It wasn’t likely you were going to be as good as Henry James.

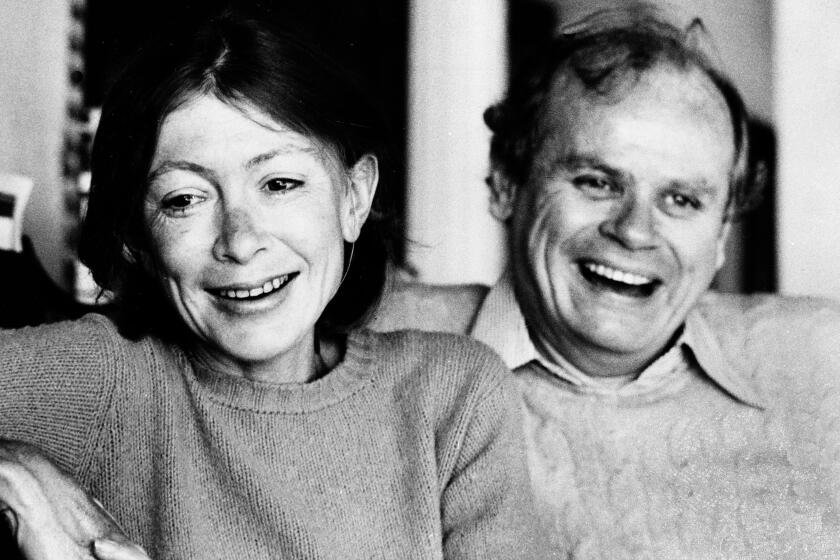

I thought I wanted to be a writer or an actress. It was undefined. I was a guest editor for a month at Mademoiselle magazine in New York when I was a junior at Berkeley, and the following year I won a contest at Vogue and they gave me a job in New York. By the time John [Gregory Dunne] and I got married in 1964, I had published “Run River.”

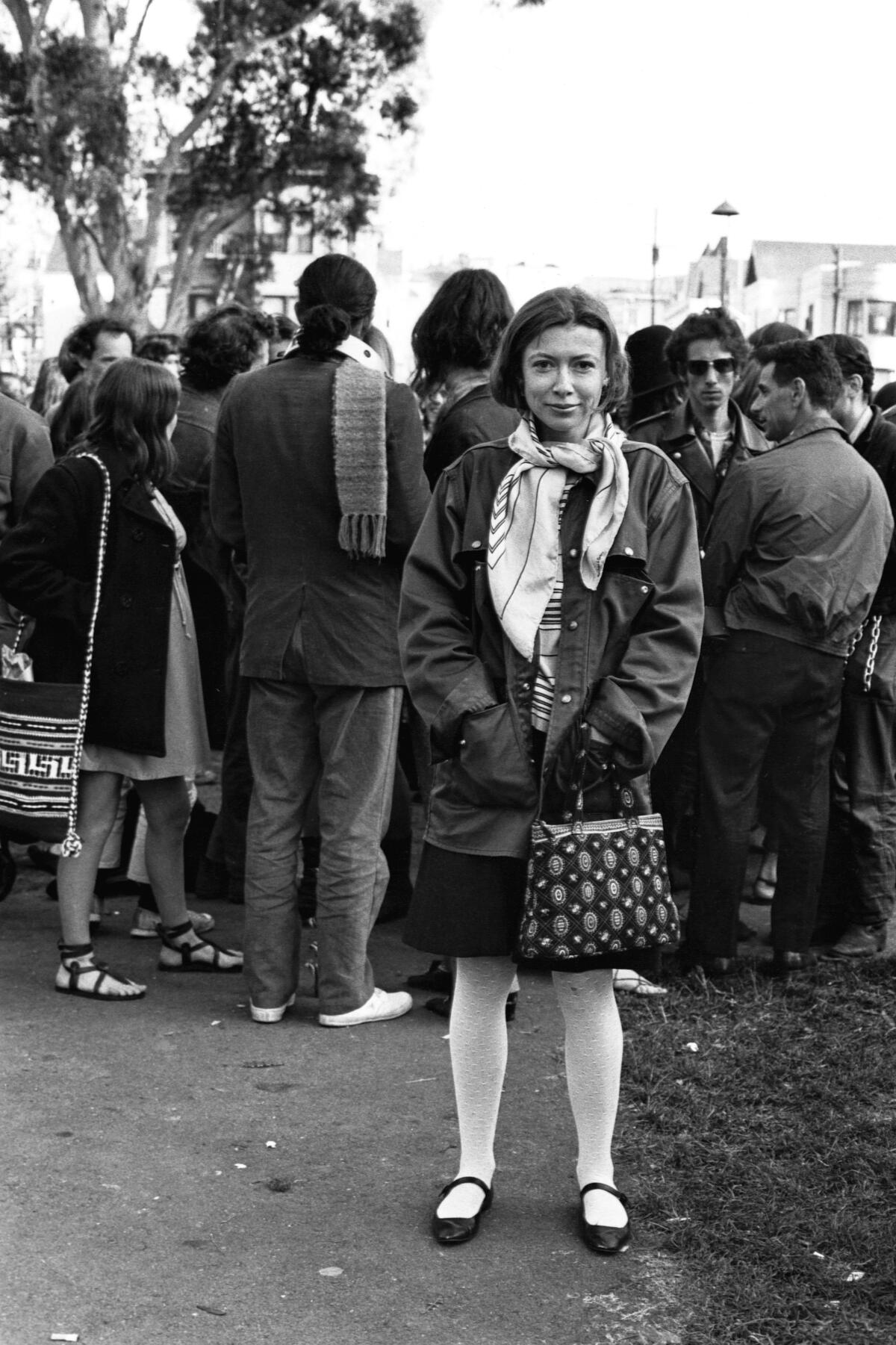

Once we decided to move to California, Los Angeles seemed the obvious place because a) we had this demented idea we could make a living writing television and b) I got depressed in San Francisco. I changed the idea for the novel I’d been not writing to another idea, which I was not writing, which turned out to be “Play It as It Lays.” But when I finally got around to writing that, I practically wrote it all in one session.

The author, who died Thursday, produced decades’ worth of memorable work. Here’s our guide to starting — or continuing — your Didion journey.

We rented a house sight unseen. I put an ad in the paper, and I got an answer from this couple who had a huge piece of property in Portuguese Bend. We paid very little rent, but part of the deal was the exteriors could be used for movies. I remember a Chrysler getting washed out to sea because they were shooting a Chrysler commercial in the surf and wouldn’t believe me when I said the tide was coming in.

My family didn’t perceive California as an easy place to live, and it’s not a particularly easy place to live. A place like Sacramento that floods every year isn’t particularly easy. Los Angeles isn’t easy. It’s easy to get your clothes to the dry cleaners, and it’s got big supermarkets. But think about the fires. You don’t need winter clothes, but at the same time your house can go.

I think people who grew up in California have more tolerance for apocalyptic notions. However, mixed up with this tolerance for apocalyptic notions in which the world is going to end dramatically is this belief that the world can’t help but get better and better. It’s really hard for me to believe that everything doesn’t improve, because thinking like that was just so much a part of being in California.

You thought if you bought a house, of course it was going to increase in value. If you bought a piece of property, of course it was going to increase in value. Of course you could sell it for a subdivision. And that was just at the crassest level. But you really believed that the town was going to grow for good. The dam was going to help the river. All these kinds of fixed wrong ideas. But there they are, fixed.

Growing up in California influenced everything about me. I can’t imagine not having grown up in California. Look around this apartment. It’s full of flat horizons. I have to look at flat horizons.

Excerpted from “State of the Arts: California Artists Talk About Their Work,” © Barbara Isenberg, 2000.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.