Commentary: Why Grand Avenue and Frank Gehry are L.A.’s path out of the pandemic

- Share via

Go ahead and put your crystal ball away. You don’t need it. We know that Los Angeles already had its intractable problems — homelessness, affordable housing, traffic, fires, earthquakes, drought, pollution, income inequality, long-standing systemic racism. There is little doubt that the financial fallout from the nasty novel coronavirus has made matters only worse.

We also mercifully know one certain way to help: Build and renovate concert halls.

On the surface, that no doubt sounds idiotic — economically, socially and in just about every other way. It’s not. It is the simplest, surest, most affordable means of turning this town around. Better still, we’re already nearly there. So please, bear with me.

Let’s take a short stroll downtown along Grand Avenue between 1st and 3rd streets. If you haven’t been there for a while — and there is a good chance you haven’t, what with the Music Center, the Broad, the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Colburn School closed since the middle of March — be prepared to be startled. A hulking skeleton of the Grand is fast rising across the street from Walt Disney Concert Hall.

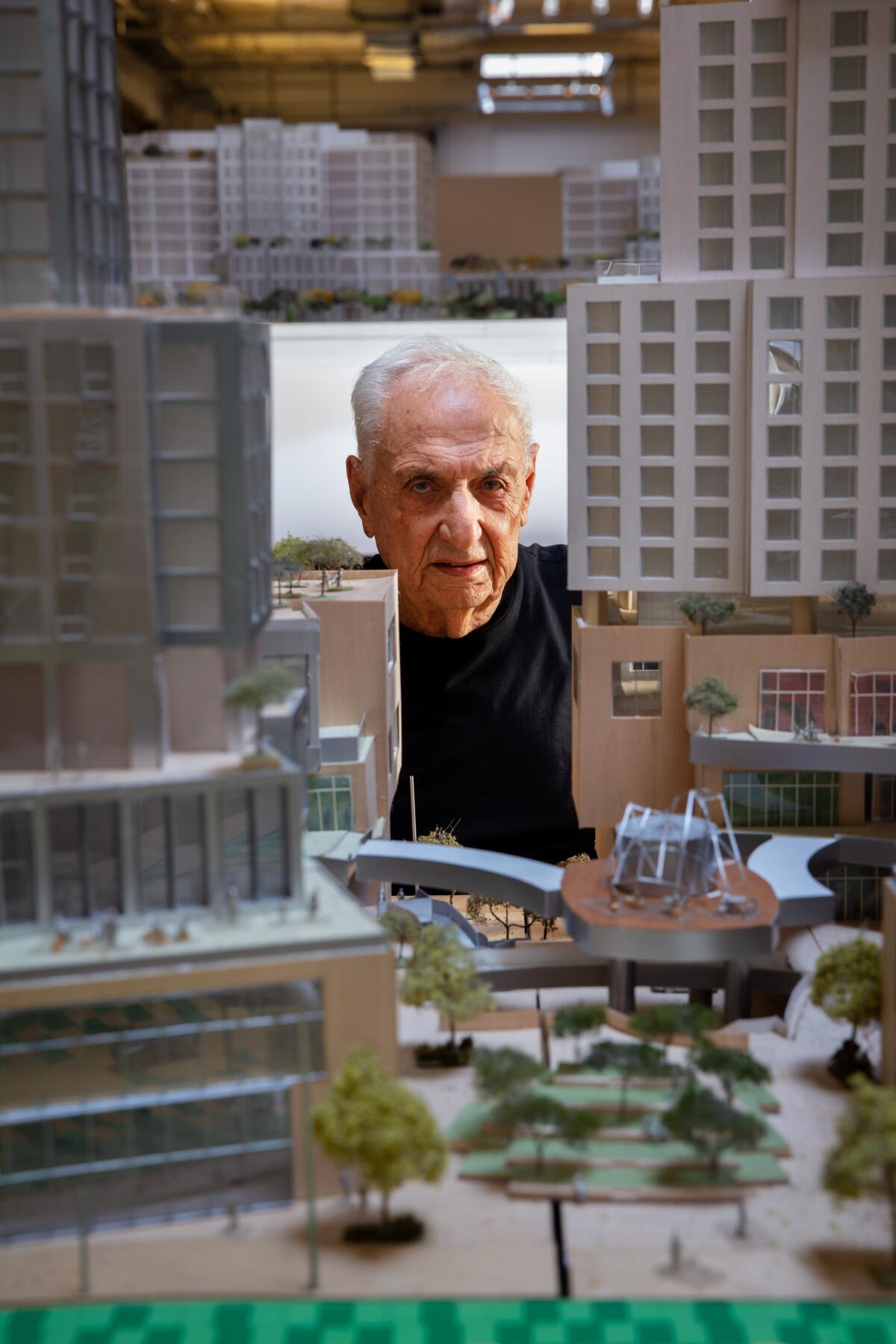

When completed at the end of the next year, this monumental complex, designed by Frank Gehry, will provide the urban foundation for a world-class, world-destination arts avenue. A mixed-use project, it will contain a hotel, housing (including affordable units), shops, restaurants, movie theaters and public open spaces.

Done right, the Grand has the potential to make Grand Avenue the cultural beacon for a city without a center, a place that stands for and is for all of L.A. Done right, Grand Avenue becomes the Grand motivator, elevating a city’s spirit and inspiring it to deal with pressing needs.

Done right means building the concert hall complex that Gehry has designed for the Colburn School too. The Colburn has purchased a parking lot at 2nd and Olive streets. Gehry’s proposal is a stunning crystalline glass structure that immediately catches the eye and holds a hall of about 1,000 seats for concerts, dance and opera. The building also would house a smaller cabaret for experimental and late-night performances, plus dance studios and a restaurant. Much of what goes on inside, particularly in the studios, would be visible to the street. Lighted at night, it promises to be stunning.

What would truly enliven the venue is a proposed plaza that Gehry has designed across the street, where another parking lot stands. That site would have a state-of-the-art sound system for free outdoor concerts. A large wall at one end is designed for projections of selected events in the new venues, just like the famed Wallcast concerts that have proved such a sensation at the New World Center, the concert hall and conservatory in Miami Beach that Gehry designed.

Gehry calls this the foundation of the foundation of the Grand. It humanizes all around it. Were the block of 2nd Street between Olive and Grand to be made pedestrian, we’d gain a grand connection with MOCA, the Broad and Disney Hall.

The new Colburn venues promise a late masterpiece by the 91-year-old architect that not only would complement his Disney Hall but also greatly enhance it, especially if we keep our think-big hats on. In a recent Zoom conversation with the ever-feisty Gehry, just out of the pool from his daily mile swim, he described how he envisions Disney as an evolving structure taking its place in this new environment. Along with proposals for restoring items cost-cut from the original plans — nightly projections of concerts on Disney Hall’s steel skin, an orchestra pit inside, an indoor-outdoor café in front and the store moved to the rear — the architect has a host of arresting new ideas.

Gehry has re-imagined BP Hall (the space inside Disney where preconcert talks are held) as an in-the-round chamber music venue, in the style of the miraculous Pierre Boulez Saal he designed for Berlin. He has plans to convert the little-used Keck Amphitheater into an enclosed jazz club and to replace the little-used staircase on 1st Street with a hip glass-enclosed bar that he would like to be called the Fleischmann, in honor of the late Los Angeles Philharmonic manager Ernest Fleischmann, responsible for Disney.

Do all this. Close too a short stretch of Grand Avenue to car traffic. Voilà, a scene. More than that, a kind of arts polis, a democratic gathering place for arts and ideas.

Imagine people spilling out of the Grand to concert halls, theaters, clubs, museums and the plaza, with an illuminated Disney as spectacular, cubist movie screen lighting up the sky with the concerts inside. No place in the world has such an indoor-outdoor arts epicenter. Nothing could be more in the L.A. character. We’ve got the year-round weather, and it’s unfortunately going to get only warmer and drier.

Grand takes on more and more life, the more you think about it. Accessibility has to be the key, and the new Metro Regional Connector Project will provide new stations on Spring and Hope streets. MOCA and the Broad are free to the public, as will be the events in the plaza. Already a world leader in diverse programming, the L.A. Phil can help set the tone that this needs to be an art center available to, and representative of, L.A.

A center needs radii. The Metro Purple Line Extension will run west to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and, farther down Wilshire Boulevard, to the new venue that UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance is making out of the old Crest movie theater in Westwood.

But the real beauty is how the Grand Avenue projects can connect aspiring diverse young artists with communities in other parts of the city. The Crenshaw/LAX Transit project will add public transportation from the YOLA Center in Inglewood (scheduled for completion in December) that Gehry has designed for the L.A. Phil’s youth orchestra and education programs.

In our discussion, Gehry announced that he’s designing a community arts training center in South Gate that he envisions as part of his massive L.A. River project. Wooden bungalows could house community arts training facilities for YOLA, LACMA , the Colburn School, L.A. Dance Project and others, all of which Gehry said are eager to get aboard. (The Colburn, L.A. Dance Project and LACMA have all confirmed their interest in the South Gate project.)

We pride ourselves on being the most diverse major city in the world. Grand Avenue is well poised to be our exalted multicultural meeting place. For just one example, bring the Street Symphony from Skid Row to a sparkling new Colburn concert hall, and let’s see how quickly we start to think about potential, not problems.

The last thing we need the Grand to be is another fancy-schmancy mall full of the same-old chains, a West Coast replica of the much-criticized Hudson Yards in New York City. Gehry says the project is having difficulty finding high-end retail to move in. Perhaps that’s a silver lining to the dark financial storm clouds seeded by the COVID-19 pandemic. Could the Grand be locally sourced instead? Were it to be a 21st century L.A. bazaar, who wouldn’t want to go there? After a year or two of pandemic separation, just think of how badly people will need to congregate. Just think of how badly a city in recession will need a place like Grand Avenue to avoid the economically elitist trappings of sterile, corporate places like L.A. Live.

Once you start to look for it, opportunity exists around every corner. The U.S. is the only major country without a major international arts festival. Grand Avenue, anyone? There is nothing like a festival to bring a city back to life — or to take on a new life. Just ask Edinburgh what an international arts festival did for its spirit and economy after World War II. Paris, London, Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Warsaw, Salzburg, Lucerne, Tokyo, Hong Kong — all used postwar arts festivals to rebuild public confidence and coffers.

For that, we need to do something else. For a quarter of a century, the Music Center has put off its promised renovation of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. It’s too big. Its acoustics are too dull. It’s dowdy and needs updated stage facilities. Opera these days is the most exciting, revolutionary, probing theatrical art form everywhere but in the U.S. Los Angeles Opera could change that if had the right facilities. A great city needs a great opera house, and a great modern city needs a great modern one. It is no coincidence that many of China’s latest architectural wonders are opera houses.

Who’s going to pay for it? That should be the easiest question of all to answer. The city and county obviously should take the lead. They have an enormous amount to gain. As a generator of income and tourism, this investment would pay for itself over and over again. Gehry’s $100-million Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao brought what was a backwater Spanish city into the limelight and billions in economic activity for the region over the last two decades.

Government should lead, but let’s face it, government won’t lead. I ran this vision of Grand Avenue past former country Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, a champion of the arts. He loved it. But for later, he insisted. Not now. There is too much else on our plate.

But now is exactly when we need to act. Think what is at stake. In 2026, we celebrate America’s 250th birthday. In an era of profound reexamination of American history, the arts tell that story with the most nuance, emotion and self-awareness. In 2028, L.A. hosts the Summer Olympics and its accompanying arts festival. Here, we show the world something worth watching.

As the nation frets about its old monuments and worries about its future, we must build new monuments genuine in the celebration of who we are, monuments capable of generating optimism. Build is what this country did during the Great Depression in the 1930s with the New Deal, including federal programs like the Works Progress Administration. San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House was a WPA project.

There was incredible pressure to abandon building Disney Hall in the 1990s. L.A. was dispirited by an earthquake, riots and recession. The L.A. Phil had a crushing debt, but it persevered. Now L.A. has a 21st century icon, and the L.A. Phil is the model of success.

Alas, the short-sighted hand-wringing has begun anew. Somewhere along the line, the Colburn School lost its moxie; fundraising appears somewhere between never begun and stopped for good. Gehry said the school is treating him like he doesn’t exist and will not make public his models, which I saw a year ago. They are dazzling. That’s crazy, considering what the school has to gain, especially were it to operate the venues with a sense of civic and artistic generosity.

Gehry’s price tag for the Colburn venues, including revenue-producing underground parking, is $310 million. That is $5 million less than the combined selling prices of the mansions that Lachlan Murdoch and Jeff Bezos have bought here in the last year.

The Disney Hall renovations do not yet have a budget, although they do not appear to be particularly expensive. There aren’t yet proposals for the Chandler. But if we can’t do something this important, why should we have faith that we can do other terribly important things?

This town is home to great wealth. During the Great Depression, Hollywood flourished, and it will again. The tech world is doing very well, thank you very much. It was been reported that U.S. billionaires have profited to the tune of $685 billion during lockdown. The real bottom line: If any city has resources like ours but is not civic-minded enough to afford a life-affirming core, it’s doomed.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.