Column: Is it better to protect banks or people during crisis? Now we have an answer

When a financial and economic crisis strikes, policymakers have only two options.

One is to protect the financial system â cutting interest rates, pumping reserves into the banking sector, preventing big financial companies from collapsing. Thatâs known generally as monetary stimulus.

The other is to protect people â pumping money into household budgets, strengthening safety net programs such as unemployment insurance, allowing the government to step in as the source of family income when employers abandon them through layoffs and shutdowns. Thatâs fiscal stimulus.

Members of Congress, opinion leaders, and ultimately voters decided that the âcrisisâ of rising public debt represented a more pressing challenge to the nation than soaring long-term unemployment.

— Gary Burtless, Brookings Institution, on the failings of post-Great Recession stimulus

For decades, economists and politicians have debated which is better.

The debate is over. COVID-19 delivered the answer.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

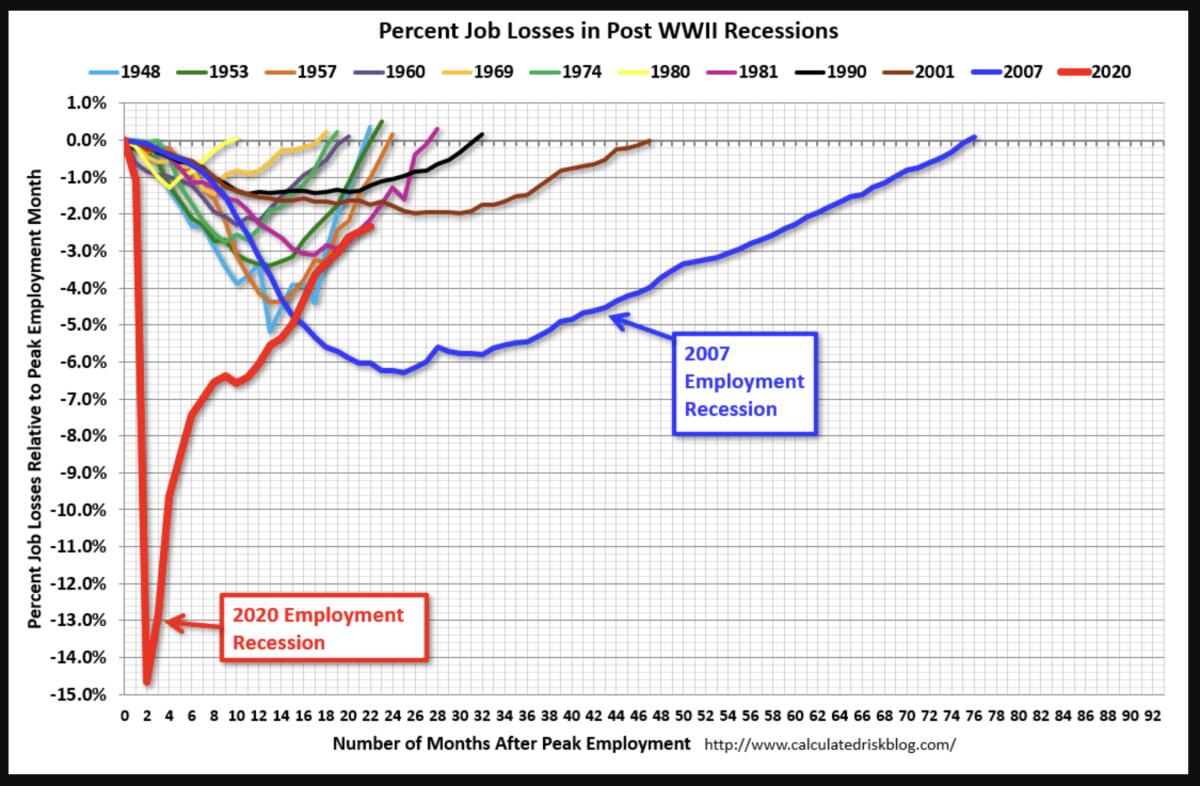

The U.S. governmentâs $4-trillion outlay to keep Americans whole during the depths of the pandemic has resulted in a spectacular recovery â indeed, the fastest jobs recovery from the lowest nadir of the 12 American recessions since World War II.

Whatâs particularly telling is the contrast between the course of this downturn and the last one, the Great Recession of 2008-09, which at the time was the most severe recession since the war.

Today, two years since the U.S. economy was effectively frozen to fight a novel coronavirus, nonfarm employment has almost returned to its level in February 2020.

The job-gain narrative is competing with the inflation narrative in assessments of the economy, and the inflation narrative is winning.

Government statistics show that on a seasonally adjusted basis, employment has reached 150.4 million, about 2.1 million below the 152.5 million level of two years ago, a deficit of about 1.4%. Thatâs a record-shattering recovery from the bottom of the freeze in April 2020, when employment abruptly fell by 22 million jobs, or 14.4%, to 130.5 million.

That was the steepest collapse in employment of the postwar era, easily outpacing the 6.3% employment loss from January 2008 to February 2010. Two years into the Great Recession, however, employment was still falling; it wouldnât return to its pre-recession level until May 2014, or about 76 months after the recession began. That was the worst job loss since 1948 and the slowest, longest job recovery.

What accounts for the difference in the two rebounds?

Some of the explanation certainly belongs to the difference between the pandemic slump and those that came before it.

The Great Recession began with a collapse in the overheated U.S. housing market, which metastasized throughout the international financial system. The 2020 recession was caused not by a seizure in the financial markets but by a deliberate effort to limit the sort of personal contacts known to contribute to COVIDâs spread, such as school classes, entertainment and travel.

That suggested that the downturn could be short and amenable to government action to restart business as soon as the threat of the virus passed.

But another difference was the nature of the government response. Drawing on lessons learned from the Great Depression, policymakers tended to favor monetary response in 2008, especially at first. The Federal Reserve and other central banks flooded the financial markets and banks with capital and liquidity. After the collapse of Lehman Bros. in September 2008, they publicly promised that no other major financial institution would be allowed to fail.

The expiration of the Child Tax Credit means 3.7 million more children in poverty. Is this the America we want?

âPolicymakers congratulated themselves that they had avoided another Great Depression,â UC Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen observed for a lecture series in 2014.

The recovery effort didnât exactly lack for fiscal stimulus. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, signed by President Obama in February 2009, initially provided $787 billion in funding for increases in the size and duration of unemployment benefits, a middle-class tax cut and infrastructure construction.

Benefits of safety-net programs such as food stamps were increased and expanded, and state governments got grants to protect education and transportation spending.

Yet even at the time, economists argued that the funding was too meager to bring the economy all the way back. Things only got worse from there, as the U.S. and Europe veered toward austerity.

In 2011, Obama agreed to spending cuts of $1.2 trillion over 10 years. In 2013, Obama and a Republican Congress resolved a conflict over the federal debt limit, the Affordable Care Act and the threat of a government shutdown by enacting the âsequester,â an economically catastrophic legislative maneuver to force an 8.5% cut in federal spending. âAll this took a big bite out of spending, aggregate demand and economic growth,â Eichengreen wrote.

The political pushback had begun in 2010, which gave Republicans majority control of the House and increased their footprint in the Senate (albeit still a minority). The ultimate result was a premature unwinding of fiscal stimulus, which began to be withdrawn well before the economy had recovered.

âThis was the single worst error in macroeconomic policymaking following the financial crisis,â Brookings Institution economist Gary Burtless wrote, an oft-quoted conclusion.

âFor reasons that may seem mysterious to future economic historians,â Burtless added, âmembers of Congress, opinion leaders and ultimately voters decided that the âcrisisâ of rising public debt represented a more pressing challenge to the nation than soaring long-term unemployment and the underutilization of U.S. productive capacity.â

The anti-deficit crowd is wrong about deficit spending. Donât let them kill the Build Back Better plan.

Looking back, the monetary stimulus may have been too successful. Once the banking system was stabilized in mid-2009, the urgency for further economic assistance ebbed. The entire program was caricatured as a bailout of banks and mortgage borrowers, contributing to the rise of the Tea Party and other conservative critics.

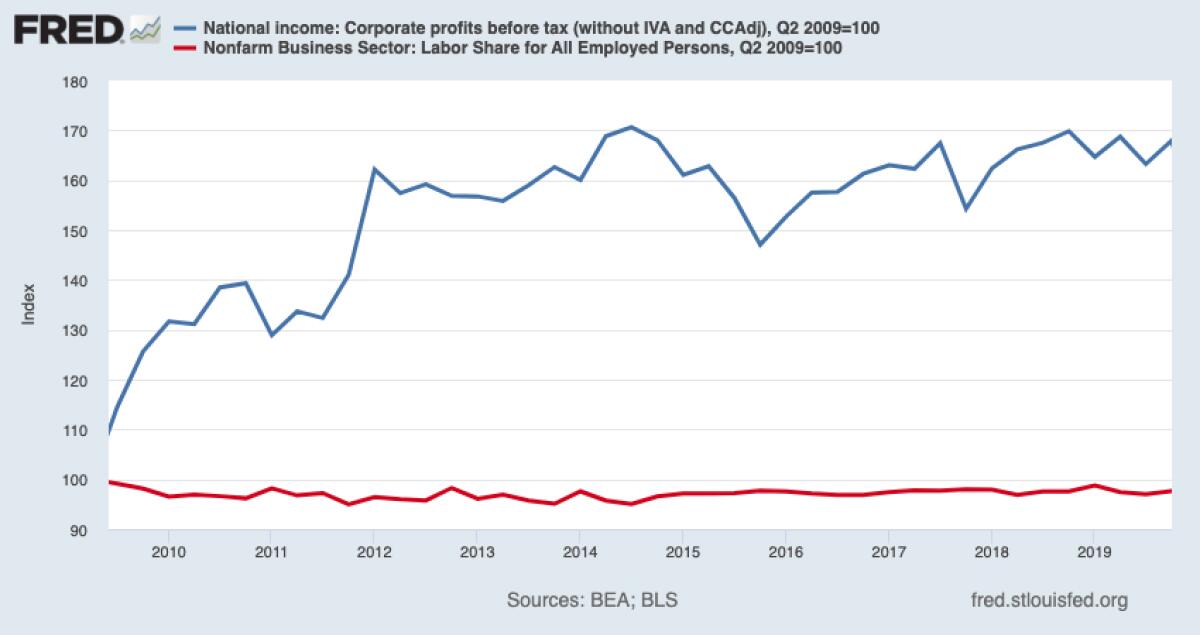

But the lessons of the Great Recession recovery werenât overlooked by policymakers confronting the next crisis. One lesson was that monetary stimulus can be very effective, but for a relatively narrow slice of America. The Federal Reserveâs slashing of interest rates effectively to zero produced spectacular growth in corporate profits and stock market returns in the succeeding dozen years or so.

âA mostly monetary stimulus left behind most of the American population,â observes investment manager and financial commentator Barry Ritholtz. âThe top 10% of America owns 89% of the public traded equities; there are 82.51 million owner-occupied homes. This means that the Federal Reserve response benefited somewhere between the top 10 and top 25% of Americans.â

Heâs right. The people who were left behind were rank-and-file workers. Corporate profits were turbocharged by the low cost of capital and debt bestowed on them by the Fedâs rescue of the financial system, gaining nearly 70% from mid-2009 through late 2019. Those gains werenât passed on to workers; laborâs share of the economy actually fell by nearly 2% over the same period, according to the governmentâs Bureau of Economic Analysis.

How to compare the $600 weekly that Congress thinks is too lavish to the $3,346 the lawmakers receive

The structure of the pandemic rescue is very different from that of the Great Recession. In part that reflects the different circumstances: Because the pandemic recession isnât a crisis of the financial system, monetary stimulus is less needed. In any event, the Federal Reserve used up so much of its monetary ammunition in the Great Recession that it had very little left.

It also points to how the sluggish post-2008 recovery rewrote the political texts on economic stimulus. More precisely, it revived the orthodoxy that had governed U.S. economic policy from the New Deal through the 1960s, ending with Reagan conservatism in the 1970s â that government has the responsibility to maintain the economy, especially by supporting spending by households when business withdraws.

Fed Chairman Jerome H. Powell made that very point in testimony to the Senate Banking Committee in December 2020. âSome fiscal support now would really help move the economy along,â he said, urging the Senate to go big: âThe risk of overdoing it is less than the risk of underdoing it.â

Congress understood. Starting in March 2020, it passed three fiscal stimulus packages that were signed into law by President Trump and a fourth signed by President Biden, totaling more than $5 trillion in outlays.

The major packages included the $2.2-trillion CARES Act of March 2020, which included cash payments of $1,200 per person or more for most households, an increase in unemployment benefits of $600 a week and loans for small businesses âthe largest stimulus package in U.S. history.

That was followed by a $900-billion package in December 2020 that provided $600 cash payments to most Americans and a continuation of the unemployment compensation benefits at $300 a week, and then by the $1.9-trillion American Rescue Plan, signed by Biden in March 2021.

The American Rescue Plan continued the $300 weekly bump-up in unemployment benefits through the beginning of September, $1,400 in stimulus payments for most Americans, a continuation of increased food stamp benefits, and a child tax credit of $3,000 per child younger than 18 and $3,600 per child up to age 6.

The key to passing these historic measures may have been their enactment while fear of the pandemic and its potential economic impact dominated political discourse.

Further relief has been impossible to pass in the current atmosphere of complacency about the pandemic. A $15.6-billion measure aimed at increasing U.S. supplies of vaccines, treatments and tests and battling the disease around the world appears to be headed for extinction at the hands of a recalcitrant Senate.

But the heavy lifting has been done, and it may well provide a template for the next economic crisis. The unemployment rate of 3.8% is almost back to the pre-pandemic rate of 3.5%, considered to be close to âfull employment.â Retail sales surged late last year and in January.

Americansâ appetite for goods, along with the wherewithal to pay for them, has contributed to shortages and transport logjams that have driven inflation to a 40-year high. That may be eating away at the wage gains that American workers have been receiving in recent months, but itâs also a signal of a robust economy.

Had the austerity hawks of the last recession been running the recovery this time around, Americans would be in much worse shape. Had policymakers had the strength of conviction of todayâs leaders back in 2009, America would have been even better positioned to sustain itself through the pandemic and the cost of stimulus might have been much lower.

Letâs hope the lessons of this downturn and the last one are etched in stone, so they can provide a users manual for the next one.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.