Column: The coronavirus crisis shows what happens when a country puts its workers last

The most familiar observation about the human reaction to abject terror is the one stating that “there are no atheists in foxholes.”

We’re about to see how that aphorism applies in modern American politics.

In recent days, alarm about the economic effect of the novel coronavirus has turned conservatives who weeks ago were boasting about the shrinking of the U.S. government into raving Keynesians, proclaiming the virtues of deficit-financed economic stimulus.

We’re not writing blank checks to giant corporations.

— Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.)

The same leaders who were pushing reductions in Social Security benefits, Medicare and other “entitlements” for the working class because they were supposedly unaffordable by the richest nation on Earth now call for a trillion-dollar pump-priming for American households and industries.

Those who defended mortgage foreclosures and tenant evictions by pointing to the sanctity of contracts are now on board with legislation prohibiting both, at least for the duration of the emergency.

And many who sounded the siren about the economic drag of government deficits and the national debt are saying, “Never mind.”

Here’s White House economic advisor Larry Kudlow on Fox News: “We have to deal with debt and deficits at some point down the road, but during crises or wars, you have got to sort of not worry about borrowing.”

Some employers are adding sick leave amid the coronavirus outbreak. Others are leaving workers hanging.

Meanwhile, Democrats and some business leaders are talking about the need to avoid the mistakes of the last major economic stimulus, in 2009, which shored up banks guilty of plying Americans with unaffordable loans while leaving the bankers free to impose punishing foreclosures on mortgage borrowers.

“This time around, we’re going to have to treat creditors differently from the last time,” said Daniel Alpert, an investment banker and adjunct professor at Cornell Law School who tracks low-income employment trends, referring to the 2009 banking bailout that ushered in an era of foreclosures and evictions.

The pain and dislocation caused by crackdowns on debtors slowed the subsequent recovery. “We saw what happened when you protect creditors — the resolution of the problem is far worse,” Alpert told me.

Many households today face credit card and mortgage payments that can’t wait. Many who will be forced to defer payments will need to be protected from losing their homes or apartments because their jobs have disappeared, even if temporarily. And they will need long-term protection from creditors to prevent the coronavirus-related recession from becoming deeper or prolonged.

As the federal government prepares to funnel hundreds of billions of dollars to the private sector, the danger is that businesses will treat these new bailouts as they have before: as cash to give top executives raises and divert capital to shareholders, leaving the working class with empty hands.

Proponents of financial aid to industry are calling for strict oversight of how businesses use bailout funds.

“We’re not writing blank checks to giant corporations,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) tweeted.

In her view, companies receiving government assistance should be required to set their minimum wage at $15 an hour within a year of the emergency ending, be permanently barred from share repurchases, forbidden to pay dividends or executive bonuses for at least three years, be required to keep their union contracts in effect, and set aside at least one board seat for worker representatives.

Billionaire Mark Cuban asserted on CNBC that corporations granted bailouts in the current crisis should be permanently barred from stock buybacks, which funnel money to their shareholders at the expense of their workers and other stakeholders. “No buybacks. Not now. Not a year from now. Not 20 years from now. Not ever,” Cuban said.

Even President Trump seemed to agree, stating at a news conference Thursday that “conditions like that would be OK with me.” He repeated that position Friday.

The question is not merely whether the recognition that rank-and-file workers need immediate help, perhaps more than their employers, will take root rather than evaporate as the crisis ebbs. It’s also whether the crisis will awaken Americans to the folly of what has been a systematic dismantling of the public sector over the decades.

The safeguarding of workplace rights and income has been privatized, ceded to employers who view their workforces as expense items, not assets to be invested in. The best evidence of that trend right now is the scarcity of paid sick leave for American workers.

As we’ve reported, about a quarter of all American workers have no right at all to paid sick leave. In service industries — where employees must report to their places of employment to work and are most likely to come in contact with the public — more than half have no sick leave.

By limiting sick leave and free healthcare, the U.S. system will promote the spread of coronavirus.

That makes the U.S. unique among industrialized countries. In Britain, workers are entitled to sick pay of at least $120 a week for up to seven months, at their employer’s expense. In France, the government and employers together cover 90% of a worker’s pay for up to 30 days of sick leave, 67% after that.

In China, workers are guaranteed 60% to 100% of their salary for up to six months and 40% to 60% for up to six years after that. If you’re looking for clues to how China managed to short-circuit its surge in coronavirus cases by forcing its citizens into quarantine, you can start there.

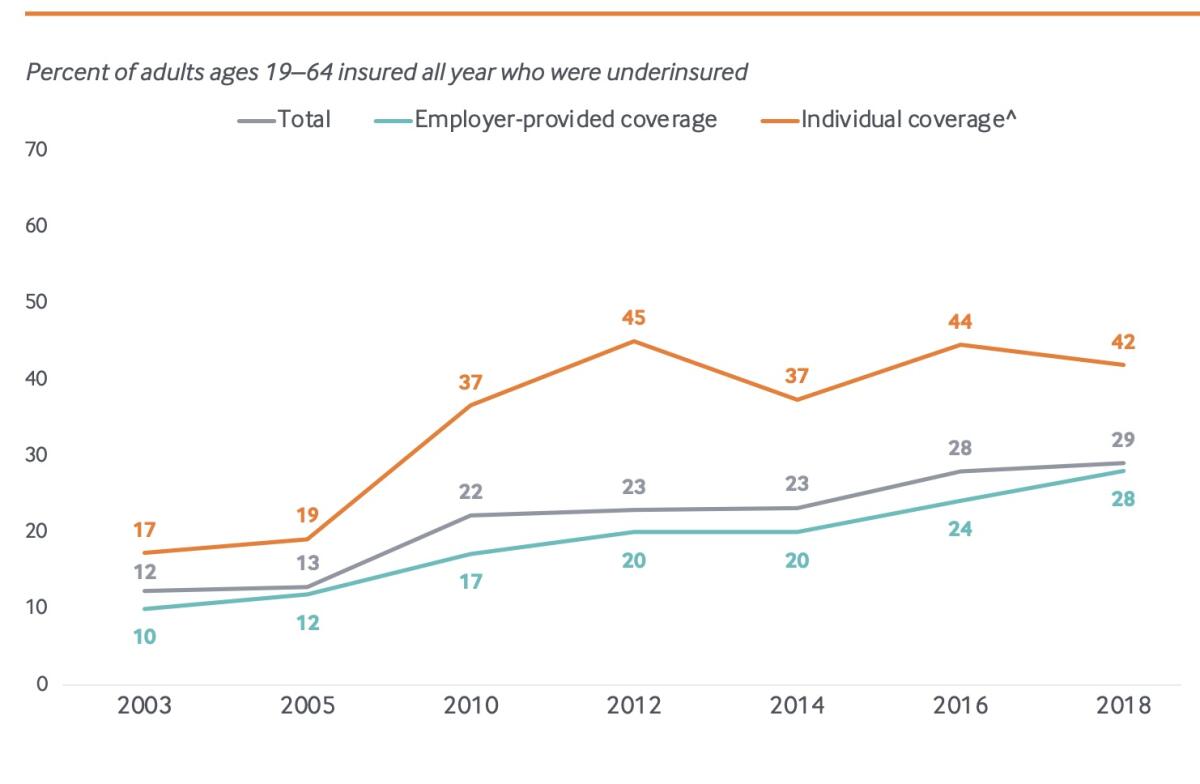

Public health and healthcare delivery also have been privatized, to the point where some 28 million people in the U.S. lack any coverage at all, and 44 million more are “underinsured” — defined as those facing deductibles or co-pays of 10% of household income, or 5% for low-income households. (Such expenses are bound to interfere with people’s willingness to get tested or treated for coronavirus-related disease.)

What the coronavirus crisis tells us about American healthcare policy is straightforward. The 14 red states that have still not enacted Medicaid expansion to cover their lowest-income residents should do so now. And Republicans should commit, as Democrats have, to universal health coverage. And Trump should withdraw his support for a federal lawsuit filed by Texas and other red states to overturn the Affordable Care Act, based on a legal theory widely ridiculed by experts.

The coronavirus crisis yields inescapable lessons about the consequences of public policies steered toward enriching private corporate coffers and executives at the expense of rank-and-file workers and public infrastructure. It has become plain that the public sector will have to be rebuilt after nearly half a century of neglect and disdain by political leadership.

The virtues of universal healthcare, whether labeled “Medicare for all” or something else, could not be clearer. The creation of a just-in-time healthcare delivery system that leaves hospital beds and supplies wanting in the face of a pandemic that was predictable — in the abstract if not of this magnitude — has placed the nation’s health and economy in dire straits.

President Trump took credit for the healthcare business doing what it would do anyway.

Will America take these lessons to heart, and act on them? The indications from previous crises and the political history of the last 50 years are both encouraging and discouraging. Let’s look at the record, and then at how things may, and must, change.

The dismantling of the federal government began with Ronald Reagan, who quipped about “the nine most terrifying words in the English language...’I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help.’”

The idea that government oversight of the free market was invariably an infringement of individual liberty quickly became an article of faith among Republicans, and even influenced centrist Democrats. In the business world, it was manifested in a newly aggressive stance against unionization, as corporations took a cue from Reagan’s pitiless breaking of the air traffic controllers union during its 1981 strike.

In fact, aversion to the government’s participation in the economy had an even older pedigree, exemplified by Herbert Hoover’s reluctance to mobilize the federal government’s resources and authority to counteract the emerging Great Depression.

What upended the tradition of governmental noninterference in the economy was fear. By 1932, industrialists visiting the White House would emerge from their meetings with Hoover to confess before the microphones that they had no more ideas to stem the economic downturn. In the long interregnum between the election on Nov. 8 and Franklin Roosevelt’s inauguration on March 4, 1933, banks across the nation failed in massive waves.

The coronavirus shows why Trump’s healthcare policies are dangerous for all

By the time FDR took the oath of office, the entire country and its leaders across the political spectrum were primed to accept almost without question the prescription he had laid out in a campaign speech. “The country demands bold, persistent experimentation,” he said. “It is common sense to take a method and try it; if it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

FDR filled his own prescription during the legendary Hundred Days, that three-month period at the inception of the Roosevelt administration that produced an unparalleled tide of legislation — a banking rescue, new regulations on agriculture and manufacturing industries, and the first of a series of actions to regulate the securities industry.

More would follow, including the 1935 Wagner Act establishing the National Labor Relations Board to safeguard workers’ rights to organize, and programs to ensure food and shelter for Americans through public works projects and make-work jobs.

But it would not be long before reaction set in. Even during the depths of the Depression, conservatives in both parties began to complain about the cost of the FDR stimulus.

It’s easily forgotten too that the second measure offered by Roosevelt for passage — after the bank rescue — was the Economy Act, urged on the president by his very conservative budget director, Lewis Douglas, through which Roosevelt imposed wage cuts of 15% across the board for federal employees and authorized sharp reductions in veterans benefits.

The atmosphere today closely resembles the dark days of 1933. Although some Republicans have balked at the scale of the fiscal response, for the most part anything goes: The Trump White House has been wide open to a stimulus program worth more, possibly much more, than $1 trillion, including extended unemployment benefits, direct cash payments to every household, and major assistance to businesses large and small. A proposal to offer businesses interest-free federal loans so they can continue to pay their employees during the nationwide forced lockdown has been taken seriously.

Trump’s economy has been great for stock investors, but not for workers.

Many consumer businesses that have shut their retail locations or reduced hours have committed to maintaining their workers’ pay at pre-lockdown levels. Best Buy Chief Executive Corie Barry said, for example, that although the company’s retail stores would shorten their hours and allow only limited numbers of patrons inside at any one time, “we are paying affected employees for their regularly scheduled hours.” Tailored Brands, the owner of Men’s Wearhouse, made the same commitment.

But those are temporary measures. Employer grants of paid sick time may not survive past the crisis unless they’re mandated by law, as they are in the rest of the developed world. The goal of universal healthcare may not be realized if the public forgets that the outcome of our overpriced patchwork system of coverage was a tide of sickness and death from the pandemic.

The crisis offers an opportunity to revive the concept, well understood from the 1950s through the 1970s, that American prosperity depends on sharing profit and productivity gains across the economic spectrum, with the labor force as well as shareholders and executives. Consider, for instance, the Project to Raise America’s Pay, a proposal developed by a team of public policy experts to combat wage stagnation. They conceived the Compensation Ratio, a measure of the relationship between a company’s total compensation and profits to the pay of its rank-and-file workforce, and tied it to corporate tax incentives.

Companies that hold the ratio steady as their earnings grow would be entitled to tax breaks; those that don’t would lose their access to tax write-offs, including the benefits of the 2017 corporate tax cut.

“The main things in the discussion about what to tie the bailouts to — a living wage, help for unions, worker representation on boards — are extremely limited,” said John E. Schwarz, a professor emeritus of public policy at the University of Arizona. “In terms of raising pay, a living wage would be modest help for many workers.”

But why not require a legally enforceable commitment to maintaining the compensation ratio as a condition for receiving a coronavirus bailout? That would do much more than a $15 minimum wage to restore labor’s participation in future economic growth.

America’s fixations with demolishing its own government and allowing the benefits of economic growth to flow only up to the highest reaches of the income scale have placed us in the fix we’re in: a government reduced to fighting a war against an elemental foe without resources, organization or brains, and a workforce one paycheck away from the brink because its leaders did nothing to see that workers enjoyed the fruits of economic growth in good times.

Now we see the consequences. Let’s hope the lessons aren’t wasted.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.