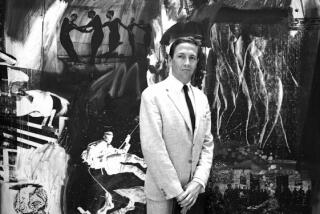

Obituaries : Arnold Rubin; Art History Scholar, Student of Tattoos

Arnold Rubin, an art historian who found social significance in such disparate places as the tattoos humans have engraved on their flesh and the floats that gather each New Yearâs Day in Pasadena, has died.

His daughter, Hannele, said the associate professor of art history at UCLA died of stomach cancer Saturday at the Los Angeles home of his longtime friend, Zena Pearlstone. He was 50.

Rubin, whose interests ranged from Nigerian dances to the Rose Parade floats, had just completed contributing to and editing âMarks of Civilization,â an anthology on another of his favored studies--tattooing.

In the book, published by UCLAâs Museum of Cultural History, Rubin made--for what is believed the first time--a scholarly examination of the tattoo and other forms of body modifications and adornments.

Cultural Contrasts

Rubin, who was tattooed himself, said in an interview last month, conducted as he was gravely ill, that he conceived of the book to show how cultural contrasts and values are expressed by the human body.

âWe put holes in our noses or we donât. We put plugs in our ears, or we donât. We put designs on our bodies or we donât.â Rubin saw those adaptations and changes as things that âtend to challenge implicitly everybodyâs definitionâ of what it means to be civilized.

In 1982 Rubin organized a tattoo party on the Westwood campus at which guests discussed what symbols and meaning their decorated skin had to them. They ranged from rowdy motorcyclists to students to a physician who estimated that he had spent more than $10,000 for the pictures and drawings that adorned him.

Before his involvement with tattoos, Rubin spent years researching the art of Africa, particularly Nigeria.

Validating the Culture

He was, he said, attempting to validate African culture at a time when people believed Africa lacked any culture of worth at all until the appearance of white people.

On Jan. 1, 1976, Rubinâs endeavors landed him inside and behind the wheel of a giant âfirecracker,â one of the dozens of floats that wended their way down Colorado Boulevard during the Tournament of Roses.

That culminated some research he began in 1971 when he was teaching a class in methods of art research at UCLA. He and his class decided to find a local artistic event that couldnât be judged by traditional artistic criteria. Pasadenaâs extravaganza seemed a logical choice.

âI had just returned from four years in Nigeria, where I had worked on mass-participation festivals,â he said a few days before guiding the float down the pink line that marks the parade route. âI decided the lessons learned in other cultures could be applied to our own.â

Joint Creative Efforts

He said the tournament first piqued his interest for two reasons: the fact that the floats themselves are the joint efforts of several people rather than a lonely artist working in a studio, and that the floats do not endure, as art is supposed to, but are âliterally made to die.â

Thus, said Rubin, who came to UCLA in 1967 from Indiana University, where he earned a doctorate in art history, âthe measure of art is not in its permanence. This is a whole body of art born for a brief life span. But this is still art.â

And he said he chose to steer the float rather than just watch because of the âunique perspective.â

âIâve danced in a mask in Nigeria and Iâve driven a float in the Tournament of Roses Parade,â he said. âIn many respects I think my life and academic experiences have come full circle.â

In addition to his daughter, Rubin is survived by a son, Gabriel. A scholarship fund is being established in Rubinâs name at UCLA. Those interested in contributing may contact the art department for details.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.