After massive ‘Panama Papers’ document leak, rich and powerful around the world deny wrongdoing

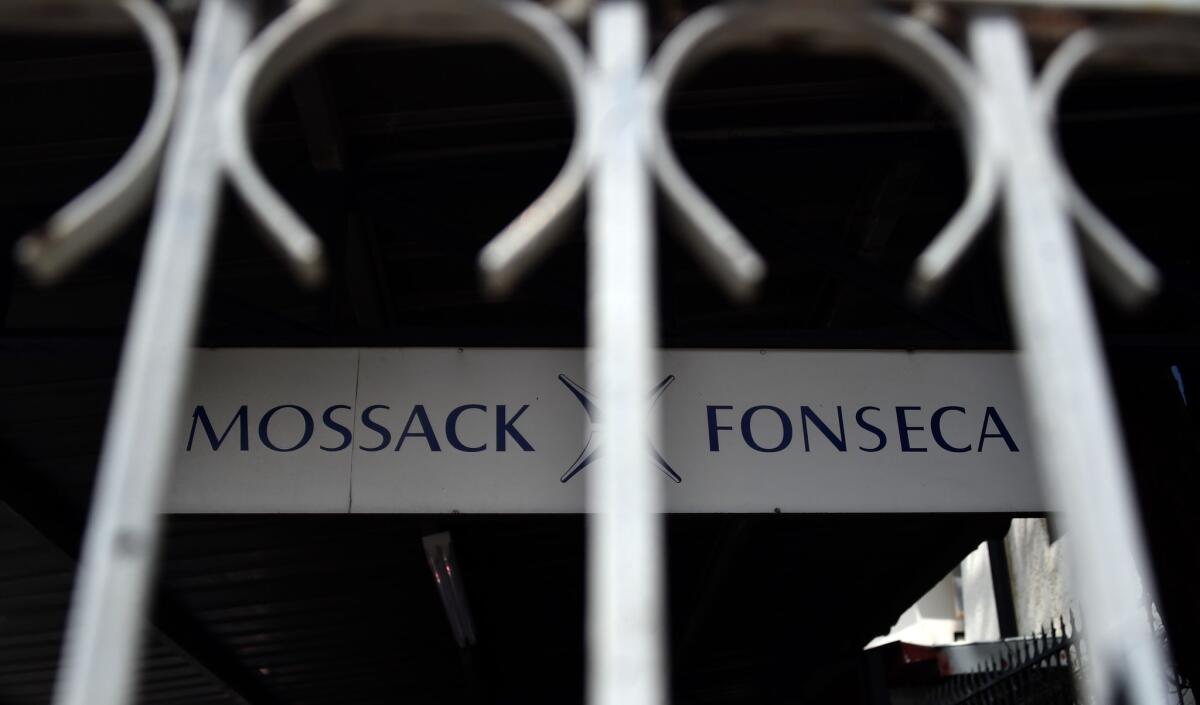

The Mossack Fonseca law firm offices in Panama City. Reports based on a massive cache of leaked documents from the firm appear to show how the world’s political, sports and entertainment elite have hidden money in offshore accounts.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — From Vladimir Putin’s best friend to the prime minister of Iceland and a revered soccer star, many of the world’s rich and powerful on Monday were scurrying for cover after the release of the so-called Panama Papers, possibly one of the largest leaks of secret intelligence ever and one that apparently reveals a vast network of financial shenanigans.

The documents from a Panamanian law firm were obtained by several international news outlets and published over the weekend. They appear to show how a who’s who in the global political and business elite — and maybe drug traffickers — have mounted complex systems to hide money in offshore accounts.

By itself, it is not illegal to hold money overseas. But the implication is that many of those mentioned evaded taxes or that money illicitly obtained was laundered through such clandestine networks.

As the scandal widened, country after country, as well as many of the prominent figures mentioned, issued denials and statements of indignation. Activist groups, meanwhile, demanded investigations into the tax havens provided by countries such as Panama and the Seychelles.

The ability to move and stash money secretly is the key weapon in any prosperous illicit business. It allows tyrants to loot nations, tycoons to rob consumers.

Laundered money is the fuel that keeps organized crime, smugglers and drug cartels running smoothly and profitably.

The Panama Papers could provide investigative leads to authorities as well as journalists for months if not years.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which took the lead in examining and publishing the trove of more than 11 million documents dating to 1977, said the information appears to show that the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca established shell companies and offshore accounts to help hundreds of people move their money.

Twelve current or former top government leaders, 61 of their associates, other politicians and thousands of businesses are named in the documents, the group said. An anonymous source first leaked the papers to the Sueddeutsche Zeitung newspaper in Munich, Germany, last year, and it in turn shared them with a number of outlets.

From Russia to China, from Iceland to Argentina, the revelations were explosive.

There was no official reaction in China to allegations that relatives of President Xi Jinping were squirreling away money. It appeared the reports were being censored on the Chinese mainland.

Iceland’s prime minister, Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson, rejected opposition calls to resign after his wife’s name surfaced in the documents.

Two of Mexico’s leading television executives were among those named, along with a major construction tycoon, Juan Armando Hinojosa Cantu, whose work for President Enrique Peña Nieto already sparked allegations of corruption. There was no immediate response from Hinojosa.

France and Australia immediately opened investigations into possible money-laundering and tax evasion.

Italy’s tax agency plans to request access to the names in the Panama Papers as it prepares to launch its own inquiry. There are about 1,000 Italians listed, according to the magazine L’Espresso, which helped sift through the leaked data.

As for Putin, the Russian president, associates were reportedly tied to more than $2 billion in secret loans. The associates include Sergei Roldugin, an unassuming cellist described as Putin’s best friend.

“The evidence in the files suggests Roldugin is acting as a front man for a network of Putin loyalists — and perhaps for Putin himself,” the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists said.

Iceland’s prime minister, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, is facing calls to resign after his wife’s name surfaced in the leaked documents.

“Honestly speaking, I can’t comment on this,” Roldugin was quoted as saying in the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta. “I have to see and understand what I can say and can’t. I am simply afraid to be interviewed.”

On Monday, the Kremlin dismissed the allegations as part of a smear campaign targeting Putin.

Khulubuse Zuma, the nephew of South African President Jacob Zuma, appeared in the Panama Papers because of interests in oil fields in the Democratic Republic of Congo through an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands. The deal was made several years ago amid suggestions he might have received favoritism through his uncle. The younger Zuma denied wrongdoing in the deal then and asserted now there was nothing new in the latest reports.

In Pakistan, an already embattled Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif found himself on the defensive after the documents alleged that three of his children maintained offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands that they use to own half a dozen properties overlooking London’s Hyde Park. Sharif himself was not implicated, and his government defended the children’s property arrangements.

In yet another twist involving the scandal-plagued FIFA organization, which governs worldwide soccer, the documents revealed a business relationship between a member of the group’s ethics committee and three men indicted on charges of paying bribes and other misdeeds, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists said.

Meanwhile, soccer’s best player, the Argentine Lionel Messi, is tied to a Panamanian shell company in the papers, the consortium reported. He is already under investigation on suspicion of tax evasion in Spain, where he plays.

Mossack Fonseca, the law firm, denied wrongdoing and issued a statement saying that the information ricocheting around the planet was full of inaccuracies and that its industry practices are misunderstood.

“The facts are these: While we may have been the victim of a data breach, nothing we’ve seen in this illegally obtained cache of documents suggests we’ve done anything illegal, and that’s very much in keeping with the global reputation we’ve built over the past 40 years of doing business the right way, right here in Panama,” the statement said. “Obviously, no one likes to have their property stolen, and we intend to do whatever we can to ensure the guilty parties are brought to justice.”

Transparency International, a nonprofit organization that studies corruption, whistle-blowing and secret financial practices globally, praised the document dump for “shedding light into the murky world of secret offshore companies.” Companies can incorporate in the U.S. without revealing sources of money.

“It’s not just the Virgin Islands and Panama where kleptocrats and criminals go to launder their illicit wealth,” said Shruti Shah, vice president of Transparency’s U.S. chapter.

Times staff writers Shashank Bengali, Jonathan Kaiman and Robyn Dixon contributed to this report from Mumbai, India, Beijing and Johannesburg, South Africa, respectively. Special correspondents Mansur Mirovalev and Aoun Sahi reported from Moscow and Islamabad, Pakistan, respectively.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.