As Mexico cracks down on migrants, more risk the dangerous train known as La Bestia

The freight train La Bestia has reemerged in recent weeks as a preferred mode of travel for Central American migrants.

- Share via

Reporting from Arriaga, Mexico — They gathered at dawn in this railyard in southern Mexico, contemplating their next move: catching a ride on the roof of La Bestia (The Beast) — the name migrants use for the notorious freight train that winds its way through Mexico toward the United States.

“Climbing on the top looks very difficult, especially with the kids,” said a dubious Carlos Onan Galo Perez, who had traveled from Honduras with his wife and their three children. “I’m worried.”

He had heard about the dangers: the criminal mobs that terrorize travelers, the risk of falling and losing an arm or leg, or worse. Mexican police recently reported that “delinquents” tossed several migrants from La Bestia in the state of Veracruz, leaving one dead and two with severed limbs.

But the train has reemerged in recent weeks as a preferred mode of travel for Central American migrants after the Mexican government, under pressure from the Trump administration, started making it more difficult for them to cross Mexico on their way to the U.S. border.

Just last year, legions of migrants traveling in caravans passed from Guatemala through the Mexican state of Chiapas largely unimpeded. Thousands more were given humanitarian visas early this year allowing them safe passage northward, keeping in line with campaign promises from Mexico’s new president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, that migrants would be treated with respect and compassion.

Now Mexican immigration agents and federal police staff checkpoints along the highways, and truckers and other motorists face fines if they give lifts to migrants. In April and May, Mexico detained a total of 43,258 foreigners, more than double the number during the same period last year.

Meanwhile, deportations have also risen significantly. The increases reflect both heightened enforcement and a surge in arriving migrants.

The trek north could become even more difficult this summer as President Trump has intensified efforts to strong-arm Mexico into taking additional action. On Thursday, he announced that the United States would impose a 5% tariff on all goods from Mexico as of June 10 and that the tariff would increase to 25% by Oct. 1 “until Mexico substantially stops the illegal flow.”

Galo and his group viewed La Bestia as less likely to be subject to raids than public buses or other vehicles — which is why they wound up in this railyard, amid idle boxcars and stray dogs, waiting for the train.

Galo and his wife, Lidis Reconco, knew how difficult it could be to reach the United States, 1,000 miles from here.

They had both already made the long trek to Mexico’s northern border earlier this year, leaving their children at home with relatives to join separate groups of migrants traveling en masse from Honduras.

“I heard about the caravans and thought, ‘This was an opportunity for me and my family, a chance to better ourselves,’” explained Galo, 35, a slim, energetic figure who was a laborer back in Tegucigalpa, the capital, but struggled to find work.

Galo made it to the city of Piedras Negras, across the Rio Grande from Eagle Pass, Texas, where he was among some 1,800 migrants held in a factory-turned-shelter. His wife reached Tijuana, where she stayed with a brother she had not seen in six years.

Seeing throngs of migrants stranded at the border, Reconco said she experienced a kind of epiphany.

“I first thought that the voyage would change our lives for the better, but then I felt differently,” recalled Reconco, whose reserved personality contrasts with her husband’s exuberant character. “What would become of our children if we were away for a long time?”

Her brother offered some counsel: “Go back to Honduras, then bring the kids, and you’ll be able to cross much easier.”

U.S. laws restricting child detention have helped fuel a surge in asylum-seeking families converging on the U.S.-Mexico border — to the ire of the Trump administration, whose officials have assailed the practice of bringing children as “shields” to get released in U.S. territory.

“Trump accuses us of using children as shields, and maybe some do,” Galo said. “But I’m doing this because it is the best hope for my family.”

Galo and his wife reached a decision: The two would return to Honduras, rest, and embark on the long venture anew, this time as a family.

They left Honduras in early April, soon arriving at Mexico’s border with Guatemala, where they waited a month until the three children — Carlos, Sheri and Shirli, ages 15, 10 and 8 — received visitor cards allowing them to travel in southern Mexico, but not beyond. Both parents already had temporary legal papers for Mexico — on humanitarian grounds — from their earlier attempts.

In early May, the family set out by bus for this sun-scorched town, a key terminus for La Bestia.

The comings and goings of the freight trains are a matter of mystery and speculation. There is no public schedule. But one evening, after Galo and his family had spent two nights outside a Catholic shelter here sleeping on cardboard mats and blankets, word filtered in: A train was expected to depart at 6 a.m.

At dusk, the migrants packed up their belongings, burned their trash and set out for the railyard, about a mile away. But there was an ominous portent: Galo had received a cellphone video clip of a police raid on a La Bestia spur outside the northern Mexican city of Monterrey.

“Leave us alone!” a woman pleaded in the video as Mexican authorities ordered migrants to descend from the train.

That evening, the Central Americans, numbering about 100 or so, crashed in the central plaza of Arriaga, across the street from the railyard. The children played on the swing sets and jungle gyms before huddling beneath them to get some sleep.

Then, as roosters heralded daybreak, the train arrived, its whistles and groans piercing the predawn. The migrants quickly gathered their belongings and crossed the street to the railyard. Galo and his group of about two dozen huddled in prayer, illuminated by ghostly locomotive lights.

“Stay together,” Galo advised. “There is safety in numbers.”

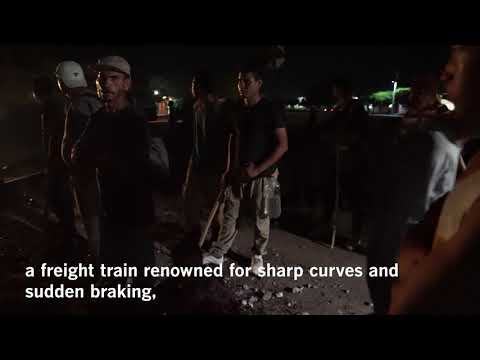

An assemblage of young men with sticks served as an ersatz security squad. Exhausted families gathered on scattered railway ties and a graffiti-splashed platform, waiting for the train to come to a halt. Women cradled infants in their arms.

Soon, many scrambled across the tracks into open boxcars, which were coated inside with cement dust, remnants of the previous cargo. Women and children entered first. The men placed wooden ties and stones by the doors to keep them ajar. All were elated to be on their way, finally.

But then railroad security men decked out in black arrived and chased them away. They sealed the boxcars, warning of the dangers of suffocation should the doors slam shut.

Now, the only option was to ride on top of the train, a death-defying endeavor. La Bestia is renowned for sharp curves and sudden braking, capable of sending rooftop passengers flying onto the rails. Low-lying branches can suddenly sweep riders into the abyss. There is no relief from the sun, rain or evening chill.

Reaching the top was itself a challenge. A gap of about six feet separated the top rungs of the ladders built into the boxcar exteriors and the roofs.

Daylight had broken.The yellow locomotive was running its engine. Some families had already formed human chains to mount the cars.

Abruptly, Galo and his group decided it was a go: Men clambered first to the top. Migrants standing beside the tracks or poised atop metal couplers between the cars tossed backpacks and plastic bags filled with clothes, water and food to comrades above.

Galo and other men lay flat on their stomachs atop the boxcars, straining to extend arms to grasp women and kids that were passed up, fire-brigade style. Children screamed. People shouted instructions, often contradictory or unintelligible in the cacophony.

“We’re going to the U.S.A.!” came an unexpected cry, in English.

That was from Julio Cesar Doblado, 44, a Honduran who said he had been deported from New York. He wore stars-and-stripes shorts and had only half a right arm — he said the rest was cut off when he fell from La Bestia four years ago in Mexico.

Galo and the others used yellow plastic rope to help secure children and luggage atop the cars. Finally, La Bestia began lurching north, its rooftop stowaways flashing smiles of relief. Ahead lay a voyage teeming with peril, but also the hope of fresh beginnings.

Special correspondents Liliana Nieto del Rio in Arriaga and Cecilia Sanchez in Mexico City contributed to this report.

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.