Human Rights Watch accuses Mexico of failing to care for young Central American migrants

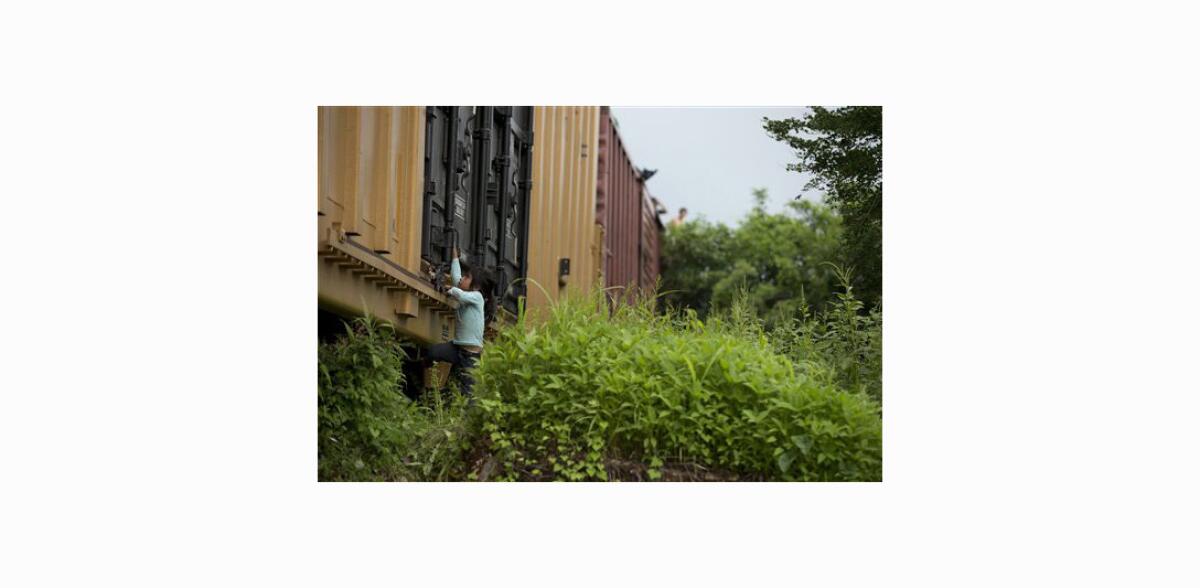

A girl traveling with Central American migrants plays on a freight train in southern Mexico.

- Share via

reporting from Mexico City — A Human Rights Watch report released Thursday portrays the Mexican government as failing to protect thousands of refugee children fleeing violence in Central America — a conclusion quickly rejected by Mexican authorities.

Tens of thousands of migrant children from the “northern triangle” of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador may be eligible for humanitarian relief under Mexican law, but only 56 unaccompanied and separated children received asylum during 2015, up from 25 children in 2014, according to Human Rights Watch.

Whether inaction on the government’s part is a reflection of bureaucracy or a calculated cost-saving measure is difficult to say, according to the report’s chief author, Michael Garcia Bochenek, who serves as senior council to the children’s rights division at the New York advocacy group.

Although Mexico has clear laws to protect such refugees and a system of shelters to house migrant children, both are being marginally utilized to benefit the children fleeing extreme violence in their home countries, the report found.

“There’s no real triage that’s happening, or if it is, it’s very few kids getting sent into the shelters,” Bochenek said.

The report, titled “Closed Doors: Mexico’s Failure to Protect Central American Refugee and Migrant Children,” is part of a larger examination that Human Rights Watch began two years ago of migration flows in several regions around the world.

Humberto Roque Villanueva, undersecretary of the Interior Ministry, called the report’s findings inaccurate and misleading. “At this moment, we don’t have any specific complaints about any child or adolescent who has been treated badly, or who has been the object of discrimination or who lacked respect for their human rights,” he said.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Referring to migrant children, he added, “It’s not exactly true to say that they don’t receive adequate attention. They receive information about their right to refugee aid, they’re sent to special shelters, and when they have to be placed temporarily in a detention center, they are given special treatment so that they’re not with the adults.”

When children are returned to countries beyond Guatemala, “they are taken by plane and they’re never alone, they’re always accompanied,” Roque Villanueva said.

The report notes that Mexico’s laws are adequate to offer protection to refugees, but contends that enforcement agencies that detain migrant children almost never inform those children of their rights, resulting in just a tiny number of applications for asylum among a population in which thousands would be eligible.

Of the few children who have received asylum, only a small percentage have also received humanitarian visas, which are good for one year and then renewable. In the first 11 months of last year, 391 children received such visas out of the 32,000 apprehended during the same period, the report said.

Immigration authorities either don’t inform migrant children of their rights, or “tell prospective applicants for refugee recognition that they will be unsuccessful, or that applying for recognition will prolong their time in detention,” according to Human Rights Watch.

The prospect of extended time in detention is a major deterrent to applying for refugee status, due to the prison-like environment of the centers where children are housed, according to the report. “I thought I was going crazy,” one child told the interviewers.

Members of rival gangs are held together, migrants told Human Rights Watch, and many said they slept on the floor with no mattress or blankets. Some spoke of a punishment cell with “no mattresses or sheets, restrictions on access to drinking water, and toilets that do not flush properly, meaning that excrement and urine overflowed onto the floor.”

The National Migration Institute, which oversees immigration as part of the Interior Ministry, released a statement Thursday saying that unaccompanied minors are offered refuge in Mexico but that youngsters reject it because they want to travel to the United States or have no reason to stay in Mexico. The statement did not directly mention the Human Rights Watch report, but said young migrants are treated well and informed of their legal rights.

Thousands of Central American children, part of the so-called surge of illegal immigration in recent years, have overwhelmed U.S. immigration authorities. Immigrant advocates in the United States have repeatedly complained that youngsters are held in substandard conditions at immigration detention centers and that few are granted asylum.

Tillman and Sanchez are special correspondents.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

ALSO

South Africa’s Zuma expected to repay money spent on home renovations after court ruling

These women in Turkey saw the need for a different kind of news, despite the danger

Why you probably didn’t hear everyone talking about these major terror attacks

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.