Murder, torture, drugs: Cartel kingpin’s wife says that’s not the ‘El Chapo’ she knows

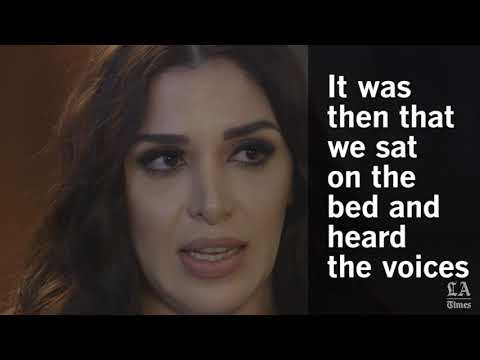

Emma Coronel Aispuro recounts how she met Joaquin Guzman at a dance – and how authorities moved in to arrest him early one morning in 2014. (Credit: Telemundo)

- Share via

Reporting from CULIACAN, Mexico — She sweeps into the restaurant dressed elegantly in black slacks and a sleeveless, pale pink blouse, a white ribbon tied demurely at the neck. Her bag is Prada. If there are bodyguards, they have waited discreetly outside.

As wife of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the notorious leader of the Sinaloa cartel, Emma Coronel Aispuro seems anxious not to cause a scene as she moves into a private room in the crowded restaurant, a popular seafood place on the sweltering banks of the Tamazula River. She smiles softly and speaks quietly.

“I don’t have any experience at this kind of thing,” she says.

Si desea leer esta nota en español, haga clic aqui.

The 26-year-old former beauty queen has never spoken publicly about her eight years of marriage to a man who has headed one of the world’s most violent criminal organizations, responsible for much of the marijuana, heroin, methamphetamines and murder produced in Mexico.

Now, she says, she wants to get out an urgent message: Her husband’s life, she says, is in danger. She fears he may not survive his current stint in “El Altiplano,” the prison where he has been in solitary confinement since Jan. 8. That’s when Mexican authorities grabbed him in a shootout in the Pacific town of Los Mochis, almost six months after his second breakout from the maximum security lockup.

Get all Times exclusive reports. Subscribe today for unlimited digital access >>

“They want to make him pay for his escape. They say that they are not punishing him. Of course they are. They are there with him, watching him in his cell,” Coronel says. “They are right there, all day long, calling attendance. They don’t let him sleep. He has no privacy, not even to go to the restroom.”

Guzman’s fabled escapes — most recently, via a nearly mile-long tunnel dug under a shower in his cell — have been a source of embarrassment for Mexican authorities, and they appear determined to avoid a third. Since his latest confinement, his wife has been allowed to see him only once, for 15 minutes. She says her husband is “slowly being tortured” and is suffering from dangerously elevated blood pressure.

“I am afraid for his life,” she says.

Guzman, 58, is facing at least half a dozen federal indictments in the United States. He is accused of leading an organization that trafficked at least 1.8 million pounds of cocaine between 2003 and 2014 to the U.S. and many other countries around the world. Federal prosecutors say his hit men carried out hundreds of killings, assaults, kidnappings and acts of torture during that period.

This is not the Guzman that Coronel professes to know. She describes her husband as a loving family man, even if he was imprisoned or on the run for the entire eight years of their marriage. She claims to know little of the details of his professional pursuits.

“He is like any other man — of course he is not violent, not rude,” says Coronel, who insists she has never seen her husband act violently or take drugs. “I have never heard him say a bad word. I have never seen him get excited or be upset at anyone.”

Her husband, she says, calls her his “queen.”

Though El Chapo has become one of the most recognized figures in the world, his wife has largely remained in the shadows. Her name emerged in September 2007, when Mexico’s Proceso magazine published a cover story about how the teenager on her 18th birthday had wed the drug lord after winning a local beauty contest. Four years later, the Los Angeles Times reported that Coronel — who was born in San Francisco and has U.S. citizenship — had given birth to twin girls in Lancaster, outside Los Angeles.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Coronel is the third wife of the drug lord, who is 32 years her senior. Her daughters are among 19 children he is said to have fathered. She dismisses, though, the oft-repeated reports of Guzman’s brutality toward women.

“He would be incapable of touching a woman with bad intentions, of trying to make her do something she didn’t want to do,” Coronel says, speaking calmly, almost in a monotone, as she described a life that started in the rural hills of Durango and somehow became a twisted fairy tale of romance, intrigue and fear — fear for a husband almost constantly on the run, for her family, for the international legal drama that lies ahead as he faces criminal charges in the United States.

It has been a life, she says, lived always “in the eye of the hurricane.”

Yet she says she has accepted that she is powerless to change it. “‘What if?’ doesn’t exist,” she said. If her husband is extradited to the United States to stand trial — probably foreclosing once and for all any possibility of another escape — she will be present.

“I will follow to wherever he is,” she says. “I am in love with him. He is the father of my children.”

::

Like many stories of love, theirs began at a dance, this one in the hamlet of La Angostura, one of many scattered ranchos in the town of Canelas, Durango, in the midst of Mexico’s Golden Triangle, a heavily fortified land of poppies and marijuana dominated by the powerful Sinaloa cartel.

“He was dancing with another girl. I was dancing with my boyfriend — at that time I had a boyfriend — and we crossed paths right in the center of the dance floor. He flirtatiously smiled at me. After a while a person told me, ‘The man asks if you want to dance with him.’ And I said, ‘OK.’ Because in the ranchos, even though you have a boyfriend, you can dance with every person who asks you to dance. So I said, ‘Of course!’”

The encounter was brief, she says, and she did not see Guzman again until several months later. “Love at first sight” it wasn’t, she insists.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Coronel was born July 2, 1989, in San Francisco, where her mother, Blanca Estela Aispuro, was visiting relatives. Her mother was a homemaker and her father was a farmer, planting beans and corn, she says. When she was 11, her parents again sent her to California, but after a year she says she returned home, having missed her family and her country life.

Months after that first encounter with Guzman, she decided to enter a beauty contest at the annual Coffee and Guava Fair in Canelas. She says proudly that she won many votes in her own right, and not, as the Mexican press has reported, because El Chapo had sprinkled cash to fix the result.

At the time, Guzman was in his customary role as a fugitive. In January 2001, he had busted out from a maximum security prison in Puente Grande, Jalisco. Still, the wanted man played the role of suitor. He made frequent visits to the Coronel home, sometimes during local fiestas or dances, though Coronel said that he did not give her lavish gifts.

“I would say what won me over was his way of talking, how he treated me, the way we began to get along — first as friends and from that came everything else,” Coronel says, blushing at the memory. “He tends to win over people by his manner of being, of acting, the way he treats people in general.”

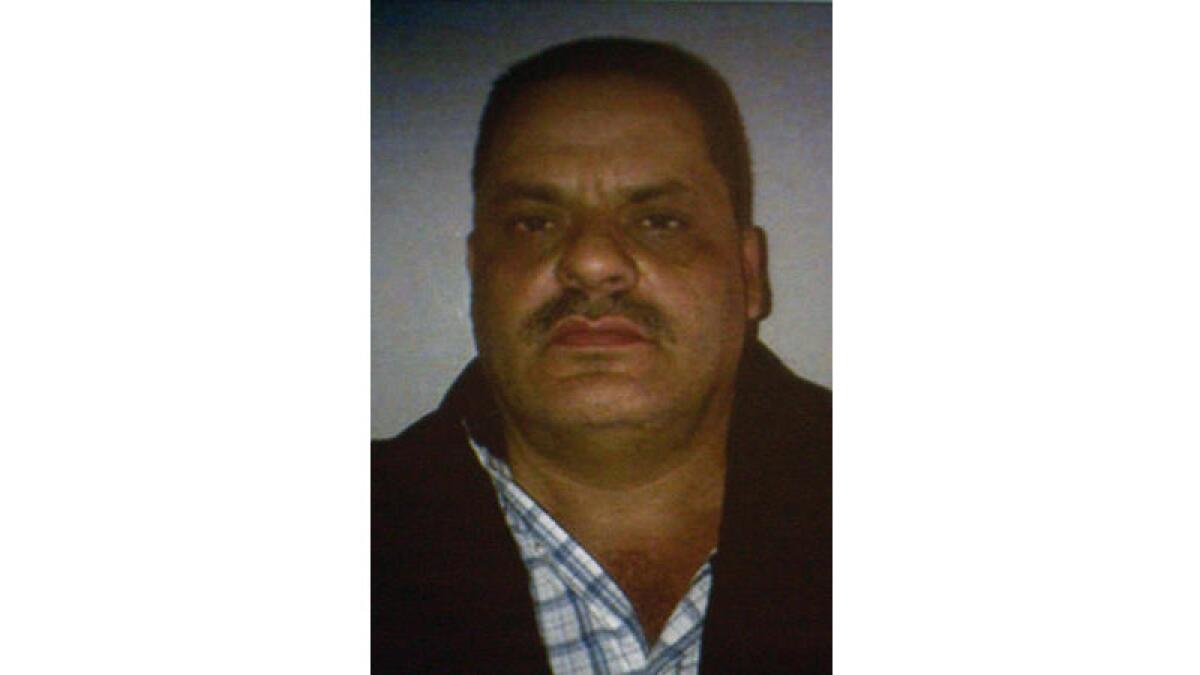

A picture of Ines Coronel Barreras, father-in-law of drug trafficker Joaquin Guzman and father of Emma Coronel. The photo was displayed during a news conference after his arrest in 2013.

A priest in Canelas married the couple at her family home on July 2, 2007, her 18th birthday. She wore a white dress, appearing “as a princess, very beautiful!” There were few guests, just relatives and friends, none of the groom’s family. Her parents never tried to stop the wedding, she says.

For years, there have been reports that the wedding was not only a union of a powerful, 50-year-old man and a teenager who had fallen in love with him, but of two influential factions in Sinaloa’s complex drug-producing hierarchy. Ignacio “Nacho” Coronel Villarreal, a high-ranking member of the Sinaloa cartel shot to death by authorities in 2010, has frequently been identified as Emma Coronel’s uncle (this has never been officially stated by the Mexican government, and Coronel insists it is not the case).

In 2013, the U.S. Treasury Department identified Emma Coronel’s father, Ines Coronel Barreras, as a major drug trafficker — and one of Guzman’s two top lieutenants — under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act, enabling the U.S. to begin blocking his assets. Coronel Barreras, 48, and his son, Ines Omar Coronel Aispuro, were arrested on drug trafficking charges in 2013, based on allegations that Coronel Barreras — popularly known as “the Father-in-Law” in the cartel — coordinated drug shipments from Mexico through Arizona for the Sinaloa cartel.

His daughter says both her father and her brother are innocent of the charges, which she believes were an attempt by the government to seize control of her family’s assets. Her youngest brother, Edgar, was arrested in August on charges of having helped Guzman in his prison escape the previous month.

Coronel says her life has been one of watching and waiting.

Once married, she moved to Culiacan, Guzman’s base of operations, finished high school and entered the university to study journalism. She saw her fugitive husband only sporadically — sometimes it was every weekend, sometimes she’d wait months before being summoned.

While Forbes magazine had named her husband as one of the world’s richest men, Coronel said she never lived a life of opulence and her husband was dismissive of the list, telling his wife at one point: “One has to ask the magazine: Where is all this money? Do they know? Because I don’t know where it is.”

Likewise, Coronel says she never saw her husband with drugs or weapons. “I went when he was already in an established location and he was very calm,” Coronel recalls.

She began to view the unusual family dynamic a bit differently in August 2011, after her twin girls were born in a hospital in Lancaster.

“When one has children, the way we think and see life changes,” she says. “For me it was then when I started thinking about the situation, that everything was kind of complicated.”

She began wondering if her daughters, now 4 years old, would spend their lives paying the price for all that has happened. “It makes me deeply sad to think that in these moments they can’t see their father, that when they’re older they can be judged, that someone might single them out for things they have no idea about.”

As for her husband, she says she has never seen him fearful or agitated, not even in moments of great stress.

“He doesn’t show at any moment he is worried about something,” she says, describing him as “very intelligent,” though he lacks formal education.

What did trouble him, she said, was his growing status as a narco-legend and his inability to control his own story.

Guzman had long wanted to collaborate on a film about his life, in part to counter what he viewed as untruths and sensationalism. “To put exactly how things are and everything that has happened until now, told by him,” she explains.

The Mexican actress Kate del Castillo, known for her role as a female drug kingpin in a popular telenovela, was exploring such a film project after Guzman, an admirer, reached out to her. It was Del Castillo who teamed up with Sean Penn, the Hollywood actor and director, on a clandestine visit to Guzman last year while the drug trafficker was still on the run. Penn wrote a colorful story for Rolling Stone about the encounter.

What drew Coronel’s wrath — and that of her husband, she believes — is a video posted with the article in which Guzman, sitting in front of a fence in a country setting, acknowledges he has worked in the drug trade since he was 15 — drawn to it because of the poverty in the rural mountains.

Coronel said that publishing the video, whose rights were granted not by Penn but by Del Castillo’s company, was a “betrayal.” Her husband, she said, believed that the footage would be used only as background information for a text article.

Del Castillo’s lawyer, Los Angeles attorney Harland Braun, said the drug lord clearly understood that the actress was there to talk about a movie — a project he said she is still pursuing. “He’s admitting [in the video] to being a drug trafficker. And the point that he’s in the drug business, that embarrasses him? The whole point of the movie is that he’s in the drug business. What she’s saying doesn’t make any sense.”

Then there was the affectionate exchange of messages between her husband and Del Castillo, leaked to the Mexican publication Milenio after his latest arrest. “You are so beautiful, my friend, in every way,” Guzman told the actress in one of them. “I will take care of you more than I do my own eyes.”

Coronel said she did not find the exchanges troubling. “I think it was the first time they met. How could it be a personal relationship?” she said. “At no time did I feel jealous of Kate.”

Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, one of the world’s most powerful drug kingpins, gained folklore status during his decade-plus on the lam, evading authorities thanks to his skill at building secret tunnels from his assorted mountain hideouts, urban safe h

::

The end of their early life together began in February 2014, when she was suddenly whisked to her husband at the Miramar Tower in the port of Mazatlan, Sinaloa.

It was early on the morning of Feb. 22 when the authorities moved in. “At 6 in the morning we heard some noises as if they were knocking down the door,” Coronel recalls. Men with guns entered the room and demanded, “Where is El Chapo?” Her husband emerged from the bathroom and told them, “Calm down, I’m here.” Coronel said she heard what she believed were U.S. drug enforcement agents at the scene.

It was not until a month later that she and her daughters were able to visit Guzman at El Altiplano. Ironically, she saw him more frequently during that period than during any other. Then, on July 11, 2015, she heard the news that he had escaped again, this time via an elaborate tunnel.

Between July 2015 and January 2016, she says, she had only two encounters with her husband, now back to his familiar fugitive role.

“He just wanted to have a nice time with his daughters,” Coronel says. “To be in peace.”

Then, on Jan. 8, she followed reports that her husband had been captured in Los Mochis, while he was reportedly escaping in a stolen car, and Coronel again found herself driving toward El Altiplano prison. She waited three days before she was allowed 15 minutes with her husband. This time, it was clear, prison guards were taking no chances.

“He was completely shackled, handcuffed, the guards stayed there with us all the time, some centimeters away,” recalls Coronel, who said she was in tears when she saw her husband’s state. “They were armed and hooded. They had helmets with cameras and they were always recording.”

As she left the prison, she recalls, her husband had a few encouraging words.

“Don’t worry,” he told his wife. “Everything will be all right.”

---------------

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This story is published as a collaboration with the Investigative Reporting Program of the Graduate School of Journalism at UC Berkeley, where Anabel Hernandez is a fellow. The interview is also being broadcast by Telemundo.

----------------

Times staff writer Patrick J. McDonnell in Mexico City contributed to this report.

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

ALSO

A new force in drug trafficking reaches Tijuana

Uber driver arrested after 7-hour Kalamazoo shooting rampage leaves 6 dead

At 15 cents a gallon, it’s the cheapest gas in the world -- yet Venezuela worries

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.