Colombian coca farmers, facing a threat to their livelihood, resist U.S.-backed efforts to eradicate cocaine production

- Share via

The anti-narcotics police arrived here in the heart of Colombia’s cocaine industry last month to destroy the coca crop. The community was determined to save it.

Roughly 1,000 farmers, some armed with clubs, surrounded the hilltop camp that police had set up in a jungle clearing and began closing in on the officers.

The police started shooting. When they were done, seven farmers were dead and 21 were wounded.

“Several friends and neighbors died on the ground waiting for medical assistance,” said Luis Gaitan, 32, who protected himself by hiding behind a tree stump.

In the end, the police crackdown appeared to have little result.

Gaitan and others soon returned to growing coca, the raw material of cocaine. The remote municipality of Tumaco, where Tandil is located, produces 16% of Colombian coca — more than anywhere else in the country.

If Colombia ever had a chance to choke off its cocaine industry, this last year might have been it. The U.S.-backed government ended a five-decade civil war with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, better known as the FARC, which fueled its rebellion largely with drug proceeds. The peace agreement promised new economic opportunities for the poor villages where coca production has long been the major source of employment and cash payments to persuade coca farmers — known as cocaleros — to grow legal crops instead.

But as the Oct. 5 clash in Tandil illustrates, things have not gone as planned.

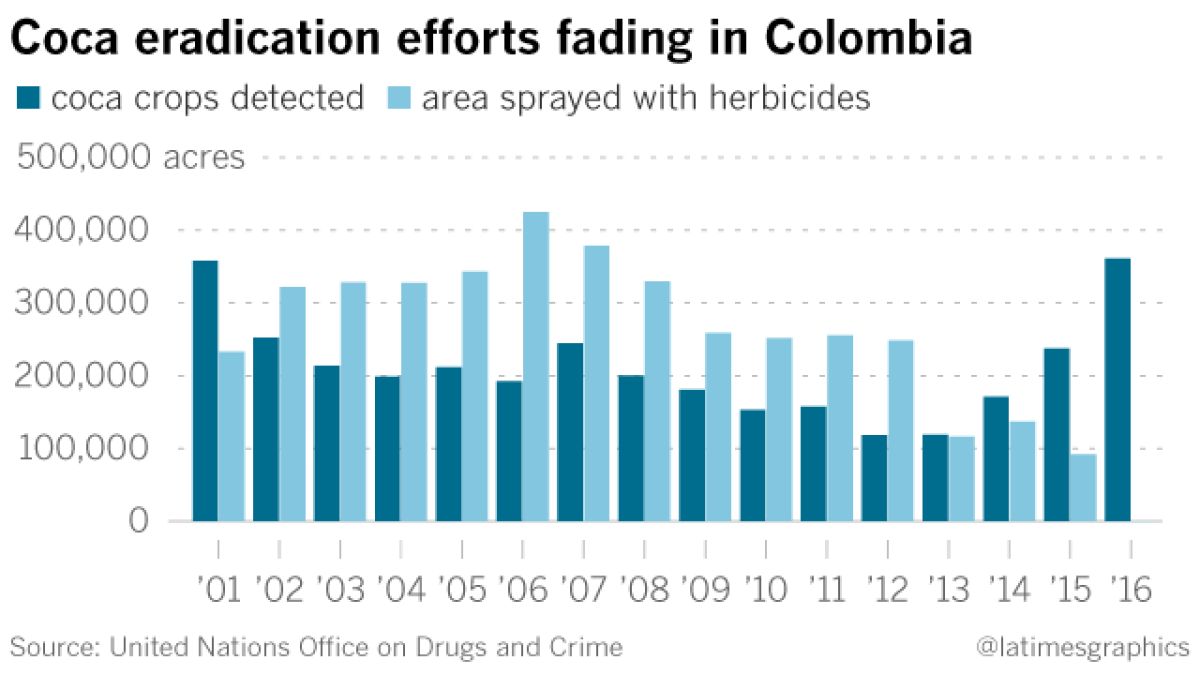

Coca cultivation last year nationwide expanded to 361,000 acres, according to the United Nations. An area about the size of Los Angeles, that’s triple the 2013 total and the most acres since 2000, when the U.S. launched a multibillion-dollar aid program called Plan Colombia to combat drugs and terrorism.

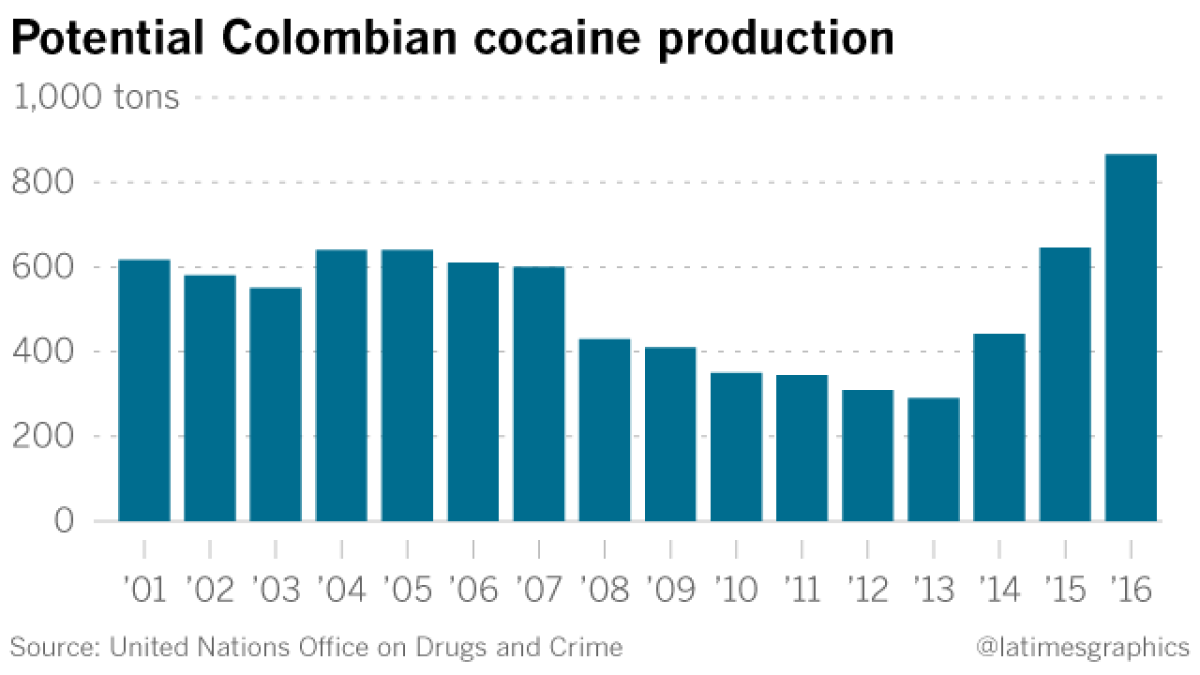

The U.S. gets 92% of its cocaine from Colombia, which exported record quantities in 2016, according to the U.S. government.

“As coca cultivation and cocaine production in Colombia increase, the United States will likely see continued increases in cocaine-related deaths, new [users], seizures and positive workplace tests,” the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration said in a report last month forecasting even more coca cultivation and bigger shipments this year.

The boom is partly due to the 2015 elimination of aerial spraying with glyphosate, an herbicide that killed coca plants but raised health concerns.

At the same time, promises during peace negotiations to pay coca farmers to switch crops backfired and spurred a rush to plant coca in time to cash in. The government in turn has been slow and uneven in making those payments largely because of budget problems.

More worrisome for the government is that criminal enterprises have been expanding their drug operations by rushing to fill the power vacuum left in the villages once controlled by the FARC. Mafias routinely issue death threats to coca farmers, warning them to not accept alternative development assistance.

“You look behind the drug problem and you find the problem of security,” said Bo Mathiasen, who heads Colombia operations at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. “It is practically impossible to think you can have a sustainable change in an area where organized crime controls the farmers.”

That reality has been playing out in Tumaco.

Situated on the Pacific coast near the border with Ecuador, the municipality is ideal territory for cultivating and trafficking drugs. The thick jungle, lack of roads and lattice of ocean inlets lined by mangroves make it difficult for authorities to patrol here for arrivals of the chemicals used to process coca or departures of cocaine shipments headed north.

“The municipality is 70% dependent on illegal drugs,” Mathiasen said. “That’s farming, manufacturing, transportation and, of course, the export of cocaine. In other words, it is completely narcoticized.”

Tumaco is also desperately poor. Most residents of the township lack sewage or drinking water systems. An ongoing plague has killed vast expanses of African palm that was the only legitimate income for many farmers, and the small fishing industry based here continues to suffer from a June 2015 oil spill that occurred when FARC guerrillas bombed a pipeline, dumping 10,000 barrels of crude into the Nulpe River.

For many, coca farming has long been the most reliable way to earn a living.

Most of the cocaleros in Tumaco are from other parts of Colombia. They started arriving a decade ago, when the FARC evicted black and indigenous groups from land that had been deeded to them under a 1993 law aimed at reducing social inequities. The rebels offered new “colonists” easy credit, security and the chance to make more money than they ever dreamed possible. A 10-acre farm might yield its operator enough coca to generate sales of up to $2,000 a month to customers who would then process it for export.

“Coca was our way out of poverty, the only means we have to feed our families, pay for our children’s education,” said Elier Martinez, president of the local coca farmers collective. “People who have come to grow coca are here because they’re looking for a better life.”

The peace deal reached in November 2016 promised to quash coca production.

Coca farmers in areas formerly held by the rebels were to receive compensation of about $400 a month for two years of coca-free farming followed by a single payment of up to $3,000 to help sustain a new crop or business.

But the promise of that program has yet to materialize for many cocaleros.

A decline in the price of oil and coal exports has left the government with a budget shortfall — and struggling to meet its commitment to the farmers. A member of the government’s peace negotiating team who spoke on condition of anonymity said that last year the Finance Ministry, citing a lack of funds, rejected a plan to pay farmers a total of $600 million immediately upon implementation of the accord.

Roughly 23,000 families of the 150,000 thought to be growing coca are now receiving payments, according to Rafael Pardo, an advisor to President Juan Manuel Santos. Some farmers, however, are not eligible for the program because their plots are larger than 15 acres and therefore classified as industrial or — as was the case for Gaitan and the 1,000 farmers in his community in and around Tandil — they don’t have clear title to the land.

Gaitan, who moved here in 2012 and earns about $1,000 a month from his 4-acre farm, said that without crop substitution payments, there is no way he could afford to give up growing coca. He said he and his wife and three children would starve.

“Coca generates work and it is sustainable,” he said. “They try to paint us as mafiosos, but we are just the bees that make the honey. Others who are more important eat the honey we produce.”

The FARC has demobilized, but there is no shortage of other armed groups to take over the coca production the rebels once controlled.

Ten drug trafficking organizations are active in Tumaco, according to a recent study by Colombia’s attorney general. In addition to the National Liberation Army, a leftist rebel group, they include the Zetas and Sinaloa cartels of Mexico.

“We know the Mexican cartels are there,” said Mathiasen, the U.N. official. “They send envoys to organize the supply chain from the source, which makes sense. You would do the same if you were exporting bananas or oranges; it’s just a different business.”

The area continues to attract young men like 22-year-old Leonardo, who asked that his last name not be used for fear of retribution by drug traffickers. He arrived in Tandil last year to work as a raspachin, or scraper, as coca harvesters are known. He said he can make $30 a day, or three times what coffee harvesters earn back home in Caldas province. He said he will soon have enough money to buy his mother a small house.

The U.S. government, which has spent $10 billion on aid to Colombia since 2000, has been frustrated that cocaine cultivation is going up, not down.

Santos set a goal that 250,000 acres of coca — roughly two-thirds the national total as of last December — would be eradicated this year. Since January, special teams of police have fanned out across coca-growing regions of Colombia, including Tumaco, to pull up coca plants.

That has led to serious tensions between the authorities and coca growers — and occasional violence. At least four cocaleros have been killed this year in 20 clashes with police. In April, farmers just outside Tumaco overpowered 50 police, held 12 of them hostage for a day and seized some weapons. U.N. mediators negotiated a peaceful ending to the standoff.

But the incident helped set the stage for the killings last month in Tandil.

“We realized the government wasn’t going to give us anything, and that the police were continuing with eradication, that there would be no agreement,” said Martinez, the leader of the collective there. “So frustration was building.”

Local farmers say they had not threatened the police before officers began firing. The police have said that they started shooting only after they had been fired upon with cylinder bombs, which resemble huge mortar shells. But police suffered no casualties and offered no evidence of bomb craters.

Police helicopters arrived about an hour after the shootings to take the wounded to hospitals.

Days later, Gaitan and several other coca farmers gathered in the jungle clearing where most of the victims were shot to bow their heads and say a brief prayer.

Since the killings, tensions have remained high.

"No one from the government has been around to apologize or talk about compensation,” said Joana Mopan, the widow of one of the shooting victims, 31-year-old Diego Escobar. “I don't know how my 13-year-old son and I are going to manage."

Eight days after the shootings, Jose Jair Cortes, a coca farmer and Tumaco community leader who advocated voluntary coca eradication, was assassinated. Many farmers suspect that mafias opposed to the government’s alternative crops plan ordered the killing as a warning to others.

The government says it’s trying to improve conditions in Tumaco to win back the trust of the farmers. The president held an emergency security council meeting in Tumaco in mid-October and announced a campaign to bring more police and troops to the area and to step up social programs. Santos said he recognized that the township’s “necessities are immense.”

“The government has not abandoned Tumaco. To the contrary,” he said in a speech. “The national, departmental and local governments have to work more as a team to stimulate participation and accelerate the substitution of illicit crops.”

Leticia Riascos, a community leader in the city of Tumaco, said most coca farmers chose their work by necessity and would happily change “if they had a real option.”

“They don’t want to leave this coca business to their children and grandchildren, don’t want to hand down the problem to future generations,” Riascos said. “We want to be good people and work for the good of the community.”

Kraul is a special correspondent.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.