At India’s Maha Kumbh Mela festival, holy smoke, dust and noise!

- Share via

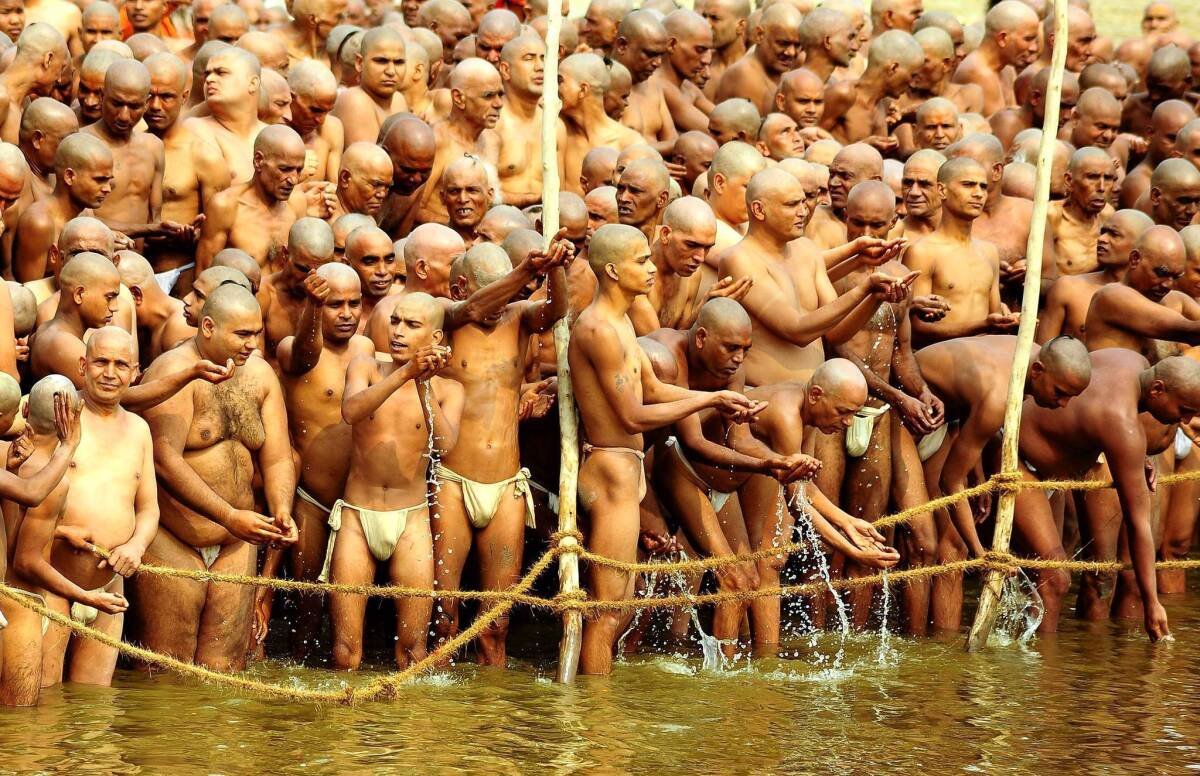

ALLAHABAD, India — It’s dusk, and the sun’s rays succumb to the twinkle of amber streetlights at the sacred confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. The day’s last bathers, intent on washing away sins and purifying their souls, take a dip in the cold, dirty water and then relax on blankets and launch boats covered in marigolds.

This is as close to peace and quiet as it gets at India’s Maha Kumbh Mela, a once-in-a-lifetime (well, this lifetime) Woodstock-gone-viral event billed as the world’s largest religious festival. How big? It’s expected to draw 100 million people over 55 days ending March 10.

Part spiritual journey, part commercial circus, the Hindu tradition is a full-frontal assault on senses too often dulled by the debilitating sameness of chain outlets, corporate-sports swooshes and designer coffee.

As stragglers head inland, they’re greeted by the smoke, dust and noise of this 4,700-acre pop-up megacity — and its 35,000 portable potties. Lost-relative messages spew from loudspeakers, clashing with movie soundtracks, Hindu chants and religious lectures blasting from hundreds of compounds adorned with fluorescent peacocks, flashing goddesses and twirling signs that read, “I love India.”

“It’s all a bit crazy,” said Baba Nirbhaya Puri, looking on from his (understated) ashram. “We’re here for inner peace, not this stuff.”

The masses arrive from dusty villages and bustling cities aboard tractors, jets and rickshaws to this place deep in India’s soul where myths breathe and gods with elephant heads and monkey bodies embody the country’s rich, textured religious culture.

“Wash your sins in the Ganges, not your clothes,” a sign entreats as women wring out saris and men shiver in wet skivvies, oblivious to the health risks of dipping in one of the world’s most polluted rivers. With 750 million gallons of sewage dumped each day into the 1,500-mile river, any link between cleanliness and godliness is an overwhelming act of faith.

There’s no shortage of that. “Mother Ganges purifies itself,” said Ram Naresh, 70, a farmer. “One drop cleanses the body and the soul.”

About 30 million devotees are expected to attend the festival Sunday, considered the most auspicious bathing day.

Held in some form every three years, with the largest crowds at the 12- and 144-year marks, when it’s believed that good karma is strongest, the festival was first written about by a Chinese traveler in AD 634, although its roots are older. Mark Twain, among the first Americans to attend, described it in 1895 as a marvel to “our kind of people, the cold whites.”

Foreigners faced with the sea of pilgrims, pickpockets, beggars, yogis and self-declared god men of this year’s 144-year festival, can relate. “It’s a bit overwhelming,” said Andrea Kjirkby, a British tourist, comparing the carnival atmosphere to an English seaside resort. “But there’s also great generosity. India is extreme. You don’t get ordinary days.”

As morning dawns over flat sandy grounds that stretch as far as the eye can see, thousands of pilgrims emerge from tattered tents, thatched huts and elaborate cupola-adorned ashrams seeking wisdom from legions of sadhus. These holy men — hermits from Himalayan retreats, thoughtful philosophers, eccentric extroverts — are fawned over by star-struck followers celebrating their work in this life and those expected to follow.

“I swam five times in the Ganges and cleansed my sins,” said Aakor Singh Maharaj, 40, a sadhu sporting a pink shirt, expensive cellphone and movie star sunglasses. “Actually I never had that many.”

In a country with a reputation for poor infrastructure and checkered garbage collection, the management of this spiritual smorgasbord is impressive. The festival site, administered by the government here in the north-central state of Uttar Pradesh, boasts temporary water pipes, power lines, police stations and 90 miles of makeshift road.

“I can’t find my guru’s place,” said Subhash Barot, a physician from Indore. “It’s overwhelming.”

At the control center, administrator Mani Prasad Mishra is ringed by supplicants seeking better locations, more electricity, new neighbors. Sadhus are allocated specific sites and pay no rent; the limited number of shops allowed into the area pay for the privilege. “It’s nothing but complaints,” he said with a sigh. “This is definitely the most challenging job of my career.”

As the sun ascends, Sri Amar Bharti Baba attracts curiosity-seekers and supplicants eager to see his right arm, held aloft for three decades in a supreme act of denial and willpower. The sadhu’s fingers have fused, their curled, blackened nails resembling talons. His left hand reaches for the hashish he chain-smokes to open his spiritual channels.

“There’s only five or six doing this in the world,” said Horst Brutsche, 57, a German devotee of 18 years known as Datta Bharti. “It’s definitely not for me.”

Tolerance hangs over the fair like the midmorning haze, the best of a Hindu tradition that finds spiritual truth in Jesus, Moses, Muhammad, Buddha as well as its own 330 million gods. “All people are God’s children, our brothers,” said Naga Baba Bodhi Giri Maharaj, wearing mutton-chop sideburns and little else. “Even Pakistanis.”

Hindu sects gently elbow for recruits in a nation with a declining interest in asceticism and the growing lure of worldly pleasures, seeking to attract pilgrims through posters, tutorials and food.

Naresh, the farmer, has learned when various ashrams ring their dinner bells. “The free food is great,” he said.

Billboards calling for the protection of sacred cows (“Treat them like your mother”) compete with more worldly entreaties to buy Close-Up toothpaste, Rupa underwear and Domino’s pizza. Near a stand selling hologram gods that wink, Sonu, 20, hawks $2 tattoos of Lord Shiva. “I change the needle every time,” he said, adjusting a dirty blanket.

A late-morning crowd heads for Sri Panchayti Akhara Nirmala’s chandelier-adorned compound in search of free tea as Sikh sadhu Nihang Singh voices reservations about all the talk of peace and love. “I’m open to war,” he said, dressed in purple robes, a spear and flip-flops. “Sometimes you must beat back evil.”

Outside, pilgrims in sandals and bare feet sidestep stray dogs scrounging for samosas past a line of naked ascetics known as nagas, many of them sitting cross-legged tending log and cow-dung fires.

One naga, Radhey Puri Naga Baba, hasn’t sat down for 10 years, even to sleep. He leaned on a pole to protect an infected right foot as he blessed people’s foreheads between hits on a hash pipe. “I’m not looking for enlightenment,” he said, advising tourists on their best camera angle. “There’s no particular reason I’m doing this.”

Another naga walked past, his penis adorned with a fake diamond ring and beads. “These are ornaments in worship of the lord,” explained the Shiva devotee, known as Lightning Baba.

Nearby, vendor Lal Madari was selling reptile bones to cure boils and thorns to banish ghosts, as he showed off a snake that drinks milk. A potential customer wearing eyeglasses, a “+/- 3.00” sticker still affixed to them, seemed interested until a sadhu shooed them both away. “He’s jealous I’m getting more attention,” Madari said, hurrying off.

About 1 million foreigners have or are expected to attend, including New Age travelers, Hare Krishna devotees and Harvard academics researching 21st century urban challenges.

For the well-heeled — Madonna and Mick Jagger are reportedly past attendees — $500-a-night tents boast living rooms, verandas and wireless Internet. Others survive on straw mats.

“It’s pretty crazy, dirty, dusty — an amazing experience,” said Zach Saltzman, 26, a backpacker from Berkeley sleeping in an ashram. “I could sure use a nice American shower.”

Veteran attendees note the growing materialism in an event expected to generate $2.2 billion in economic activity, part of what a local newspaper termed “the God economy.” The festival is mostly funded from state and federal budgets, with a limited portion covered by advertising.

“Sadhus with cellphones and tablets preach religion but aren’t living it,” Mahant Baba Bharti, a naga with Rastafarian hair uncombed for a quarter-century, said as he stood near a mobile ATM. “Those in the big tents with the music and lights, they’re posers.”

Yet for farmer Shrimoni Devi, 60, who saved for six months for her family’s $35 train fare, it’s an experience she’ll never forget.

“My daughter’s lost her job and my grandson’s taking his exams, so I’m here to earn good karma,” she said, trying to sleep as neighbors banged drums and cymbals. “It’s so exciting. I’ve never seen such a gathering.”

Tanvi Sharma in The Times’ New Delhi bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.