‘El Chapo’ trial winds up with the key question: Who’s the boss?

- Share via

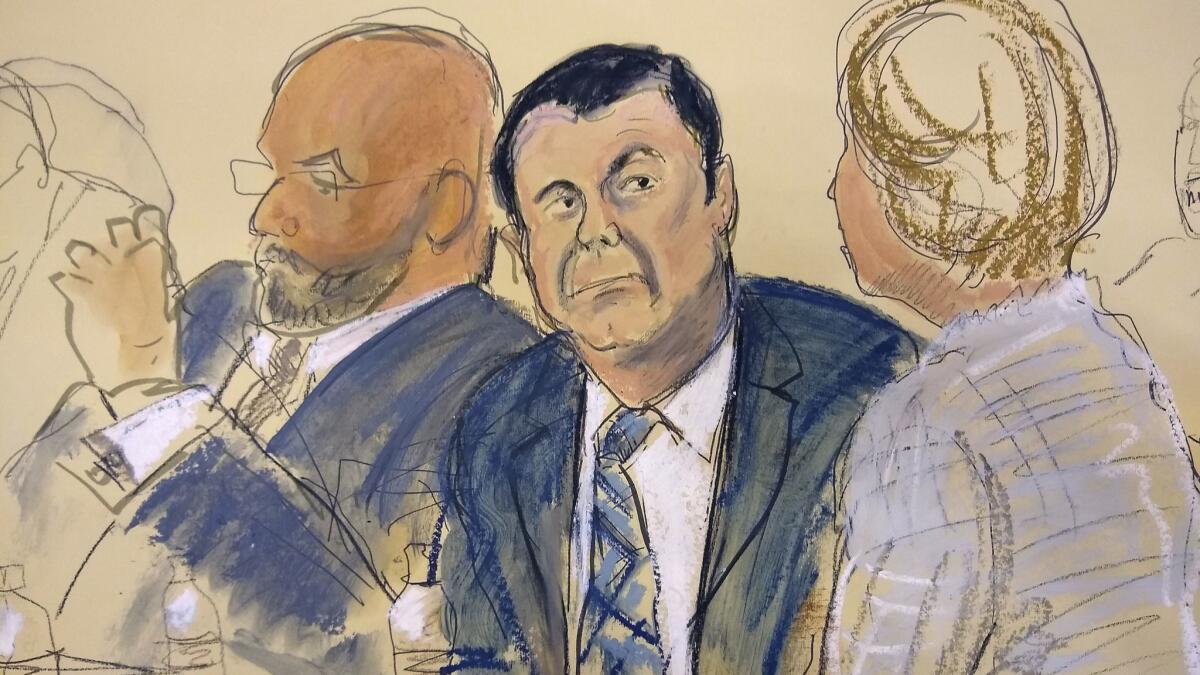

Reporting from New York — The prosecutor’s message to the jury on Wednesday morning was clear: Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman was the boss.

U.S. Assistant Atty. Andrea Goldbarg faced the seven women and five men who’ve sat for 11 weeks in a federal court jury box, across from one of the world’s most notorious drug kingpins, and asked them a barrage of rhetorical questions.

Who travels in armored cars? Who has not one, but an entire series of escape tunnels? Who owns a diamond-encrusted pistol? Who has a private communications system?

“A boss of the Sinaloa cartel,” she answered.

And the evidence for it, she told jurors, is “staggering.”

“We have presented an avalanche of evidence,” Goldbarg said during closing arguments in federal court in Brooklyn. And she spent the next several hours going through the most striking highlights of the last three months.

Guzman, 61, faces 10 criminal counts, covering accusations that he sold hundreds of tons of cocaine, meth, heroin and marijuana; conspired to murder a slew of rivals; and helped run one of the world’s largest international drug networks.

Goldbarg took jurors through every count, each violation.

She told them Guzman devised plans to successfully transport tons of drugs using cross-border tunnels, submarines and boats disguised as fishing vessels.

He smuggled some 90 tons of cocaine into the States, between 1990 and 1993, in cans that were labeled for jalapeño peppers, she said, adding that the value of the chile-can coke topped $1 billion.

She recounted the gruesome testimony one of the more than 50 prosecution witnesses gave just a few days ago.

‘El Chapo’ lawyers aim to portray Joaquin Guzman as the victim of a vast conspiracy »

“High in the mountains of Sinaloa,” two men, already bloodied and beaten, “lay in front of a raging fire,” she said. Guzman lifted a gun and personally shot each man in the head, before having them thrown into the flames, she said, recalling testimony of a longtime bodyguard to the defendant.

The grisly scene showed Guzman for what he was, Goldbarg said: a ruthless leader who used violence and corruption to “amass billions in profit” for his “criminal enterprise.”

Sure, some of the most devastating testimony against Guzman came from his former higher-ups, most of whom are convicted criminals, Goldbarg said.

But, she told jurors, “the government is not asking you to like them.”

Most importantly, she said, the testimony about drug sales, corruption and murder has been corroborated.

She emphasized again and again that what witnesses said, jurors also heard Guzman himself say — in the scores of intercepted messages and texts they heard or were read during the trial.

“You know it’s true because you heard it from the defendant’s own mouth,” she said.

She played jurors some of the key recordings of Guzman: him talking to a Sinaloa state police commander, arranging a shipment of drugs near the coast of Los Angeles, discussing a bribe.

She played video of him interrogating a man whose hands were tied around a pole. And she showed them photos of Guzman’s various tunnel systems, with their entrances hidden under showers and bathtubs.

Goldbarg ended by referencing what has perhaps made Guzman most famous — his escapes from prisons via those elaborate tunnels.

“He’s sitting right there. Do not let him escape responsibility,” she told jurors. “Hold him accountable for his crimes. Find him guilty on all counts.”

Guzman, who sat projecting calm in a dark gray suit and tie, could face life in prison if he is convicted.

Before the closing started, the morning began with a curious request from a juror: She wanted to know whether Guzman was paying for his own lawyers. The judge told her privately, he recounted to the court, that it’s a question that’s not relevant and won’t be answered. He told the court that she “agreed to strike it from her mind.”

Jury deliberations could begin Friday. The defense is expected to make its closing arguments Thursday, followed by the prosecution’s rebuttal.

The defense has aimed to portray the case against Guzman as a conspiracy and their client as a victim — less a sophisticated boss than a figurehead that a corrupt system built into a mythical scapegoat.

Goldbarg appeared to be trying to head off that strategy, telling jurors that all the government’s mountains of evidence pointed to this simple conclusion: “This is the defendant, running his empire.”

Plagianos is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.