He was the voice of a generation in Pakistan. Then pop singer Junaid Jamshed found God

Junaid Jamshed was the voice of a generation of Pakistanis in the 1990s, as the country emerged from a decade of Islamist policies that had stifled liberal music and culture.

- Share via

He burst into the national imagination with a stylish mane and sparkling eyes, riding a motorcycle through green fields and singing a patriotic pop song set to lively synthesizer beats.

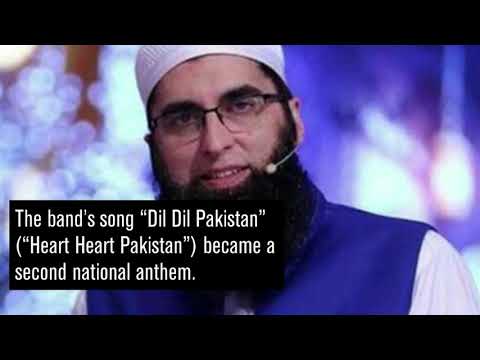

Junaid Jamshed was the voice of a generation of Pakistanis in the 1990s, as the country emerged from a decade of Islamist policies that had stifled liberal music and culture. His band’s song “Dil Dil Pakistan” (“Heart Heart Pakistan”) became a second national anthem, its upbeat video aired endlessly on television in an era before satellite channels or YouTube.

But Jamshed was uncomfortable with fame, and after a decade as a pop icon he ditched his stonewashed jeans for clerical robes and joined an Islamist evangelical movement. The transformation astonished his fans. But in many ways Jamshed’s life encapsulated the long struggle in Pakistan — an overwhelmingly Muslim nation of 180 million people — between secularism and orthodox Islam.

------------

For the record

7:42 p.m.: An earlier version of this story misspelled music fan Siddique Farooqi’s last name as Farooqui.

------------

The 52-year-old Jamshed was returning from a preaching tour Wednesday when the twin-engine Pakistan International Airlines plane he was flying in crashed into a hillside, killing all 48 passengers and crew members aboard.

As Pakistani authorities opened an investigation into the crash, Jamshed’s death set off a wave of nostalgia for his pop career and his band, Vital Signs, the country’s first commercially successful music act. The fresh-faced foursome provided the soundtrack to an era of social and economic liberalism that began after another plane crash, in 1988, killed the pro-Islamist military ruler Gen. Mohammad Zia ul-Haq.

“After that whole decade of Zia, suddenly everything was open,” said Fasi Zaka, a newspaper columnist and radio host. “We had huge hope for the future and felt that things could only go up from there.

“The way these guys captured the cultural zeitgeist of the moment, it’s hard to underestimate that,” he said. “In the consciousness of a whole generation of Pakistanis, Junaid Jamshed has been an icon.”

Out of the Islamist laws and strict morality of the Zia days, “Dil Dil Pakistan” was a ray of light. A traditional tune about love of country — the opening lyric is “Such land and sky, where to go but here?” — it featured Jamshed’s soulful voice and a jaunty Western beat that few Pakistanis had ever heard.

“We still remember that pop singer with the clean-shaven face, wearing leather jackets and jeans, with a soft and melodious voice,” said Farrukh Bashir, a senior producer with Pakistani state-run television who knew Jamshed since 1988. “He influenced a generation of youth during the last days of dictatorship of Zia. He revived pop music in Pakistan.”

The band touched the hearts of young Pakistanis with songs such as “Saanwli Saloni,” an ode to dark-skinned women in a culture where fair skin is seen as more beautiful. Its sound reached across the Pakistani diaspora, winning fans among the children of immigrants in the United States and Britain.

“Growing up as a first-generation Pakistani American, it was Junaid Jamshed who made me proud to listen to and follow the pop music scene from my parents’ homeland,” said Siddique Farooqi, a 36-year-old marketing director in Long Island, N.Y.

Farooqi, who was 8 on a visit to Pakistan when he first heard Jamshed, said the country had “lost a national treasure.”

The son of an Air Force officer, Jamshed moved on to pursue a solo career. But a decade after his debut, the country’s musical tastes were changing and Jamshed began to struggle financially. He disappeared from the pop music scene in 2001.

In the consciousness of a whole generation of Pakistanis, Junaid Jamshed has been an icon.

— Fasi Zaka, columnist and radio host

Roughly two years later he resurfaced as a prominent member of Tablighi Jamaat, an extremely conservative Sunni Muslim missionary movement. He still sang, but only naats, plaintive poems that praise the Prophet Muhammad, set to faint orchestral accompaniment.

He found a new fan base and a new career as an Islamic entrepreneur, selling CDs of his religious songs, podcasts, pilgrimages to Mecca and even a clothing line featuring modest fashions for men and women.

Longtime admirers struggled to reconcile the fresh-faced pop icon with the bearded evangelist.

“Most people I know really came to dislike him and saw him as a hypocrite,” said Tooba Masood, a journalist in the port city of Karachi. “He didn’t use any women to model his clothes. He used mannequins, because he felt it was wrong for women to model.”

Suddenly, a heartthrob who once had women throwing themselves at his feet began making headlines for what one commentator called “moderate misogyny.” He was criticized for arguing that females shouldn’t drive and for saying: “A woman is a diamond. Diamonds are meant to be hidden.”

In 2014, a flippant remark about the Prophet Muhammad’s wife — Jamshed said she faked an illness to get the prophet’s attention — spurred blasphemy allegations from hard-line religious groups that forced him to flee temporarily to London.

His death brought a new surprise for many former fans: Flying alongside him was a woman described in media reports as his second wife, with whom he had three children. Polygamy is legal for Muslim males in Pakistan but widely seen as a sign of hard-core conservatism.

The reaction to his death has underscored the gulf between secular and religious Pakistanis. On social media, old fans have reminisced about his music and ignored his turn toward Islam, while devout Muslims have praised him for leaving “a lucrative music career for the sake of Allah.”

Jamshed voiced no regrets about renouncing his earlier career. About a decade ago, Masood and her brother ran into Jamshed at the airport in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and asked for his autograph, saying they loved “Dil Dil Pakistan.”

“He said something like, ‘Please forget I used to sing,’” Masood recalled. “And he walked away.”

Special correspondent Sahi reported from Islamabad and staff writer Bengali from Amritsar, India. Staff writer Sameea Kamal contributed to this report.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia.

ALSO

In the battle for control of key oil installations in Libya, a military man takes center stage

Italy says thousands of Nigerian women who arrive as migrants are forced to work as prostitutes

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.