Ingrained cheating pervades India’s education system

Under intense pressure, some students cheat in covert or bold ways to score well on all-important nationwide exams.

- Share via

The voice that answers the number posted on the online ad is polished, confident: No one will suspect anything, he says. The gadget has never failed.

A college senior, he sounds younger on the phone but assures the caller that he speaks from experience. He gives his name as Anil and quotes his price: about $40. Minutes later he texts, offering a 6% discount.

That's the price to cheat on one of India's all-important tests, a pressure-packed exercise that holds the key to the country's most coveted colleges, universities and postgraduate programs.

Anil, a medical student in southern India who asked that his full name be withheld, was selling a tiny wireless earpiece, scarcely bigger than the head of a pin. The earpiece receives a signal from a cellphone via a transmitter. During exams, Anil conceals the transmitter under a loose-fitting shirt, texts pictures of the test questions to a friend at home and receives answers over the phone.

"There's no way anyone can even make out you using the device," says Anil, who found the earpieces in the United States and imports them in bulk, selling three or four a week on EBay to high school and college students. "I've never had any problems. You just need to have some confidence and a good friend who can help you out during the exams."

India's schools are renowned for producing hordes of talented math and science graduates, tens of thousands of whom go on to excel at universities in the United States and worldwide. But an emphasis on rote learning and the overriding importance of the exams have also spawned an inveterate tradition of cheating.

In India's increasingly meritocratic system, good scores in the nationwide tests for 10th- and 12th-graders — known as board exams — determine not only admission to the best schools but also to the most sought-after disciplines, such as engineering and medicine. Likewise, undergraduates compete for limited spaces in elite postgraduate programs. Parental pressure can be overwhelming, students say.

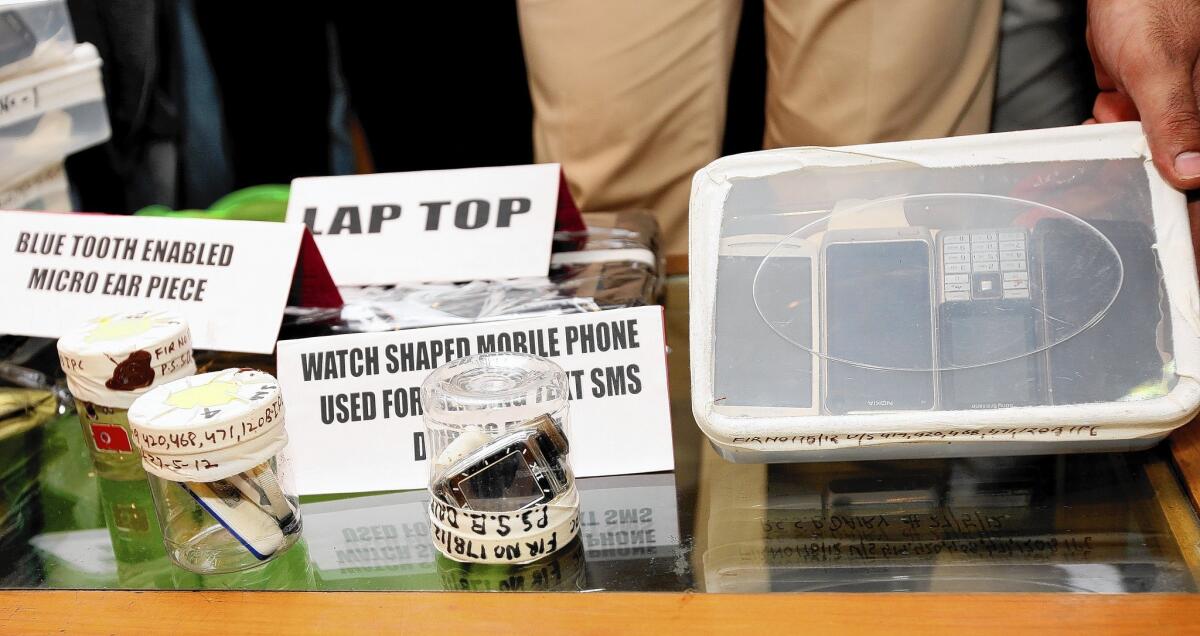

Police in 2012 display sophisticated gadgets seized in a major test cheating scandal in New Delhi. (Parveen Negi, India Today Group / Getty Images) More photos

Even for those not attending college, test results are the key to entering job training programs that offer a ladder up to the middle class.

Education officials say they are tackling the problem, but for every comical-sounding contraption like the one Anil was selling, more extreme examples routinely surface in the Indian news media once exam season begins each February.

At a school in Allahabad, in northern India, members of an inspection team were attacked with "crude bombs" last month after catching two students cheating, according to news reports.

At a test center in northern India's Bareilly district, state-appointed inspectors making a surprise visit last month found school staff members writing answers to a Hindi exam on the blackboard. When the inspectors arrived, the staff members tried to throw the evidence out the window.

You just need...some confidence and a good friend who can help you out during the exams.”— Anil

Sometimes the stories are horrifying. A 10th-grader in Uttar Pradesh, India's largest state, accused his principal last month of allowing students to cheat if they each paid about $100. The student's impoverished family could barely manage half the bribe. Distraught, he doused himself with kerosene and set himself on fire in the family kitchen. He died the next day.

At the well-regarded Balmohan Vidyamandir school in central Mumbai, 10th-grade teacher Shubhada Nigudkar didn't notice the math formulas written on the wall in the back of the classroom in a neat, tiny script until days after the exams concluded.

"There is nothing we can do at that point," the matronly, bespectacled English teacher said. "I can't prove anything. So we move on."

The problems have prompted education officials to take preventive measures that at first blush might seem worthy of a minimum-security prison. Some schools installed closed-circuit cameras to monitor testing rooms. Others posted armed police officers at entrances or employed jamming devices to block the use of cellphones to trade answers.

Still, India's national elections, which began this month, billed as the world's biggest democratic exercise, "are likely to be freer and fairer than the exams," journalist Mridula Chari wrote on Scroll, a news website.

Teachers and school officials say rogue students make up a small fraction of the millions of those who take the board exams each year. But some say the problem became worse after a 2010 national education policy that guaranteed schooling for all children up to age 14.

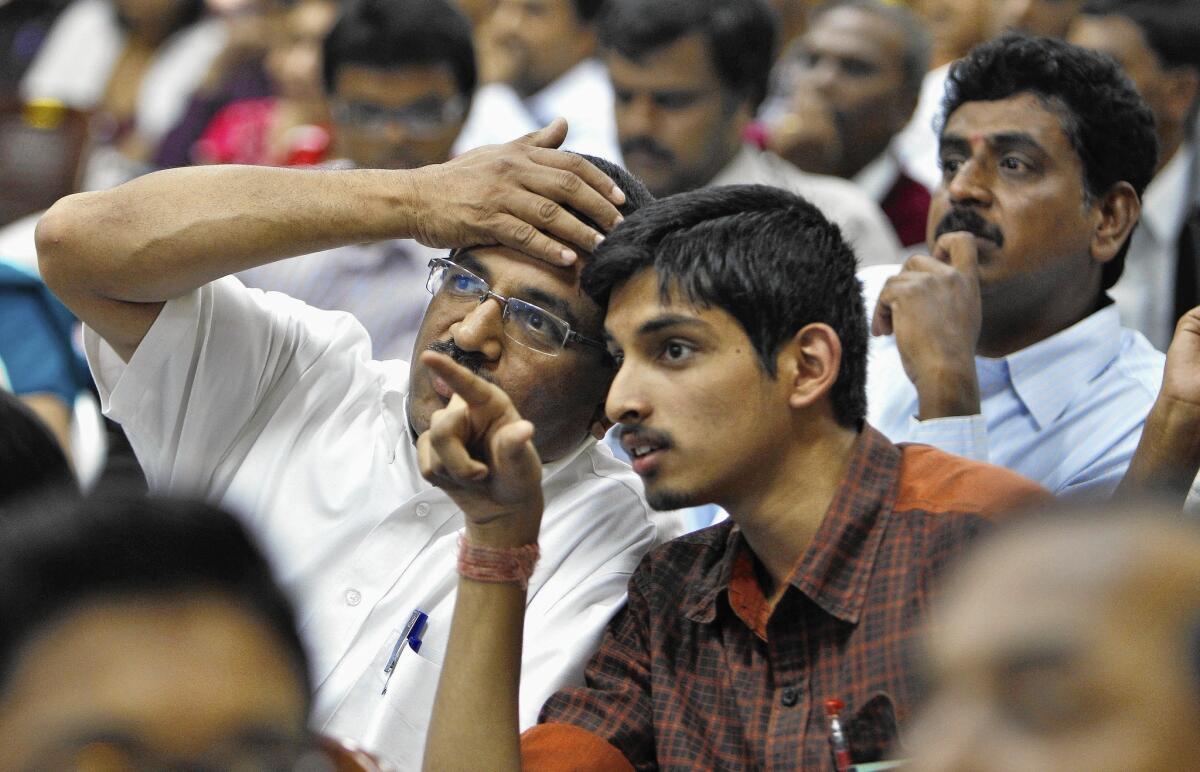

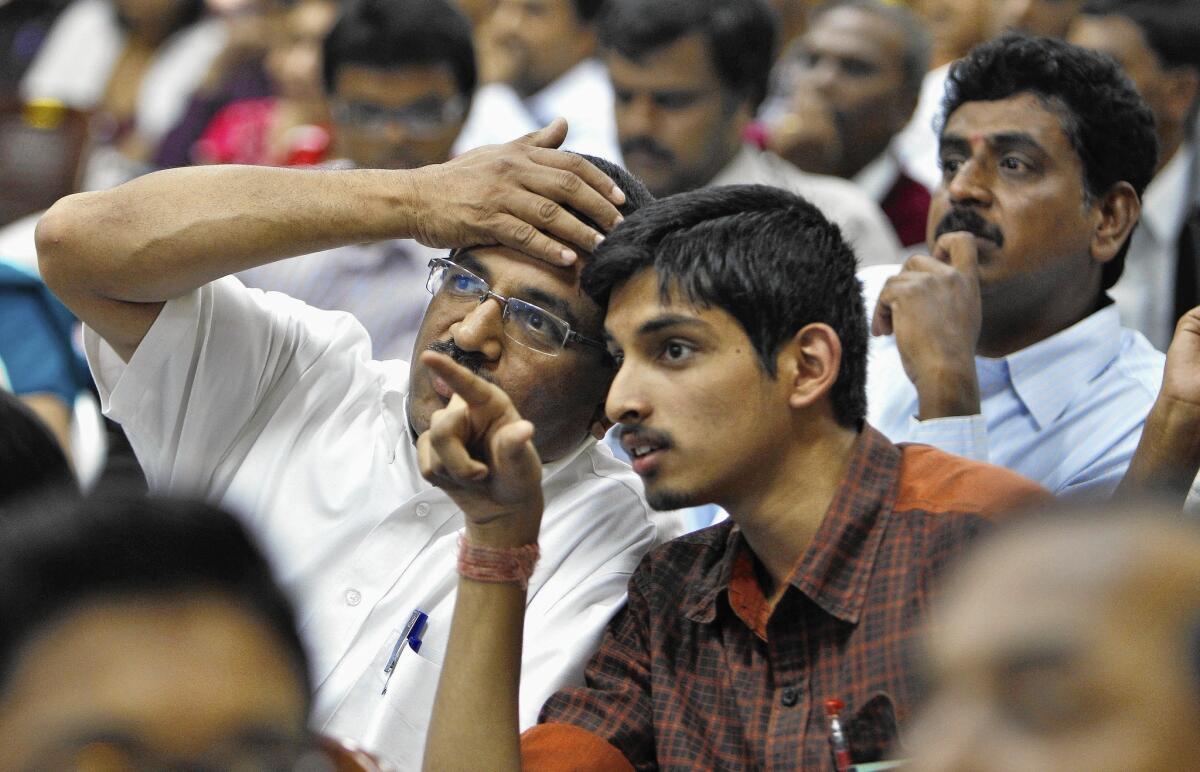

A college applicant and his father in Bangalore, India, watch a screen displaying seats allotted to students after the son passed an entrance test in 2011. (Aijaz Rahi / Associated Press) More photos

Under the law, no student will be left back until the eighth grade or forced to take a board exam until the 10th grade. Teachers say the policy coddles underperforming students and doesn't train them to take tests.

"They are used to passing. They don't become accustomed to studying," said Madhukar Yadhav, the headmaster at Balmohan Vidyamandir, a stately, wood-paneled schoolhouse in the bustling Shivaji Park neighborhood.

For rule-breakers, low-tech methods remain popular. Teachers say that hiding cheat sheets in socks, copying neighbors' answers and scribbling notes on walls are the most common tactics. Test papers routinely are leaked as well, often by low-level school employees who sell them for the equivalent of a few dollars, and sometimes by teachers or administrators whose professional standing rises if students perform well.

Enforcement during the tests can vary widely. One student who asked to be identified only by his first name, Sarvesh, said that during his 10th-grade exams three years ago in Mumbai, just one supervisor was assigned to stand watch over dozens of students.

I remember verifying most of my answers with my friends.”— Sarvesh

"For the major part of the exam, he was not present in the class," Sarvesh recalled. "There was open passing of information, noise and even discussions. I remember verifying most of my answers with my friends."

Students and teachers said the anti-cheating measures instituted this year had mixed success. In Mumbai, officials said that installing closed-circuit cameras reduced cheating by 20%, but teachers said students in at least one school in the city's Parel neighborhood disabled the cameras by pelting them with rocks.

In the eastern state of Bengal, where police stood guard outside test centers and students were checked at the entrance, the measures didn't stop people from tossing cheat sheets wrapped around small stones through windows into the exam rooms, a local newspaper reported.

"One hundred percent, we can stop this problem," said Lakshmikant Pande, chairman of the Mumbai division of the board of education in the western state of Maharashtra. "If we continue these types of efforts over two or three years, surely we can stop this."

High school students gather after taking a national exam in Noida, India, last month. So-called board exams for 10th- and 12th-graders determine admission to the best universities and job-training programs. (Burhaan Kinu, Hindustan Times / Getty Images) More photos

Veteran teachers remain skeptical, saying that school principals often are reluctant to report cheating for fear of damaging their reputations. They also said there is little incentive for a teacher to testify to a cheating case, which can trigger a laborious formal investigation.

Nigudkar, the English teacher, said that about a decade ago, the son of a senior Indian Railways official hired a lowly train conductor to take the 10th-grade exam for him. The scam was busted and the student reported to the authorities.

Yet long after his graduation, the case remains before the police, Nigudkar said, with the teacher who nabbed the cheat forced to appear at least once a year at a court proceeding.

"We learned a lesson from that," said another English teacher, Akhil Bhosle. "If we register a case, it will be a headache for us."

Special correspondent Parth M.N. contributed to this report.

Follow Shashank Bengali(@SBengali) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

For pizza vendors, Vegas expo is a slice of heaven

Judges frown on the 'lick and stick' trick, in which contestants use saliva to stretch the dough.”

Activist battles jailers' 'culture of violence'

I know sometimes trouble attracts people. But try to stay out of it.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.