In Britain, anxiety about immigration started long before the ‘Brexit’ vote

- Share via

Reporting from London — To hear European Union officials talk, the freedom of workers to move wherever they wish within the 28-member union is a fundamental principle—one they won’t alter even though discontent with free immigration was a major issue in Britain’s vote last week to leave the EU.

But it wasn’t always like that. Just over a decade ago, Britain threw open its doors to immigrants from Poland, the Czech Republic, and six other Central and Eastern European countries newly admitted to the EU—while most other EU members took stringent steps to keep them out.

Immigration must be brought to manageable levels, so we can provide for these people and make sure they integrate with society.

— Alp Mehmet, vice chairman, Migration Watch UK

The consequences of those actions are still being felt in Britain today. Poles, who represent the largest group of nonnative workers in the country, have become the target of anti-immigrant sentiment stirred up by the recent “Brexit” campaign, which culminated in Thursday’s vote.

The reversal of approaches to the movement of labor is one of the ironies of the immigration debate in Britain and its contentious relationship with its 27 European neighbors. It also hints at how deeply misinformation and misunderstandings infect discussions about immigration here, and how they can be exploited to drive public opinion.

Britons have been rattled by a sharp rise in net immigration over the last 20 years, particularly from EU countries. In 1997, EU immigrants numbered 18,000, about a third of all net immigration; in 2015, the EU accounted for nearly half of the net immigration total of about 333,000.

Of greater concern to policy-makers is that the EU newcomers tend to crowd out better-skilled immigrants from other countries.

In the immediate aftermath of the landmark referendum, leaders of the Brexit campaign tried to downplay the role of anti-immigrant sentiment.

Writing in Sunday’s Telegraph, former London Mayor Boris Johnson, the leader of the ruling Conservative Party’s Brexit movement, flatly denied that the “Leave” voters were motivated by “anxieties about immigration.”

Instead, he argued, the paramount issue was “control”—a more nebulous public discontent with bureaucratic rule-making from EU headquarters in Brussels.

Yet British Prime Minister David Cameron, an EU supporter who announced plans to resign the day after the vote, said just the opposite Tuesday during his final summit with other EU leaders. Fear of mass immigration was “a driving factor” behind the vote, he acknowledged.

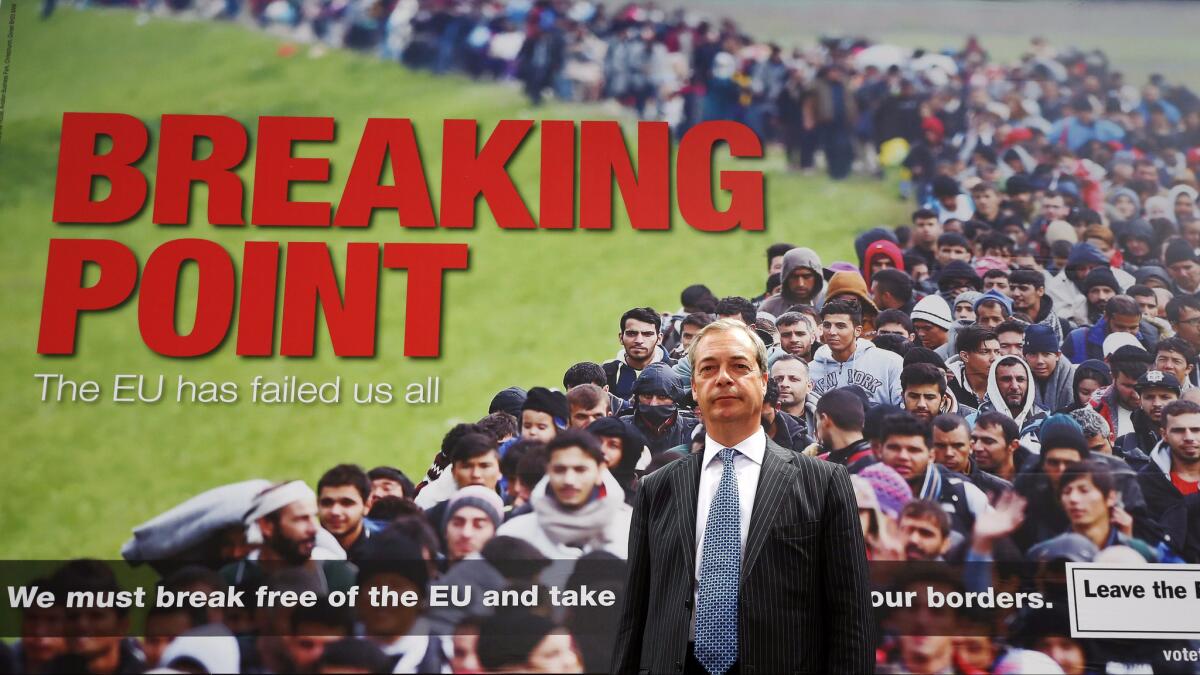

An anti-immigrant tone was an inescapable feature of the Leave campaign. At one point, right-wing politician Nigel Farage, one of its leaders, introduced a poster depicting a crowd of Middle Eastern refugees. Even though the refugees aren’t a major issue in Britain, the poster bore the legend: “Breaking Point: The EU has failed us all” and established a certain exploitative tone in the campaign.

As is often the case, the greatest anti-immigrant sentiment, as represented by the Brexit vote, tended to show up in regions with smaller actual immigrant populations, and vice versa. In the northwest of England, where immigrants account for 2.8% of the population, 58% of voters chose to leave the EU. In London, where more than a third of residents are immigrants, 60% of voters opted to stay. That could partly be a result of the voting power of immigrants-turned-citizens, but immigration advocates say it also reflects locals’ greater familiarity with the work their neighbors do—they are less susceptible to immigrant-bashing.

EU immigration has been a hot topic in Britain at least since 2004. Many Britons assume that immigrants strain government programs; in fact a higher percentage are employed than are native Britons, and the vast majority claim no public assistance.

A widely cited study by University College London found that EU immigrants have brought a net fiscal benefit—paying as much as much as $26 billion more into public coffers than they consume in services. Moreover, the study asserted, they have endowed the country with “productive human capital that would have cost the UK £6.8bn [$9.5 billion] in spending on education.”

Yet immigration critics maintain that Britain simply doesn’t have room for continued immigration at its current rate, especially of low-income workers.

“Immigration must be brought to manageable levels, so we can provide for these people and make sure they integrate with society,” says Alp Mehmet, vice chairman of Migration Watch UK. His organization places a “sustainable level of properly managed immigration” at about 60,000-70,000 a year.

The Cameron government has set an annual target of 100,000 immigrants—less than a third of the current level—but there doesn’t seem to be a clear rationale for picking that figure.

“There’s no logic to it other than it’s a round number,” says Carlos Vargas-Silva, senior researcher at Oxford University’s Migration Observatory.

What’s more important is that the mandate to accept unlimited EU immigration interferes with efforts to weight total inflows more heavily toward high-skilled workers.

British industrialists complain about the mismatch between low-skilled EU immigrants, who can come at will, and skilled non-EU citizens they can’t employ, even if they’ve been educated in Britain.

James Dyson, the entrepreneurial inventor of Dyson vacuum cleaners and other appliances, observed during the Brexit campaign that 60% of engineering graduates at British universities were from outside the EU, but “we’re not allowed to employ them..And we chuck them out!”

A 2015 Bank of England survey showed that while immigrants generally are well-represented in high-paying professions, EU immigrants resemble the stereotypical low-wage immigrant in the U.S. In Britain, more than 30% of doctors and dentists are immigrants, and about 20% are among professionals such as engineers.

EU nationals, however, cluster in unskilled occupations. Their influx since 2004 has changed the pattern—and the image—of the British immigrant.

The immigration issue had little political weight here through the mid-1990s, when net immigration was low, and sometimes negative. There was little economic rationale for EU citizens to move to Britain, because the economic disparities between their home countries and Britain were not very great.

But a change occurred in 2004. The EU admitted eight new members, including Poland, but instituted a tight lid on their citizens’ right of movement for up to seven years. Only Britain, Ireland, and Sweden welcomed the new members. Basing its expectations on previous patterns of EU immigration, the Labor government of Tony Blair complacently assumed EU immigration would remain at historical levels.

Instead, tens of thousands of workers from Eastern and Central Europe showed up. Poland unseated India, Pakistan and Ireland as the leading national source of immigration, totaling almost 1 million over the next 10 years.

“To have low-income countries join the EU was unprecedented,” says Vargas-Silva. With per capita incomes in Britain roughly twice that of Poland, and workers’ purchasing power three times as high, the prospect of working in Britain had become irresistible.

British government officials say they don’t want to cut off all EU immigration, merely apply the same standards faced by applicants from elsewhere.

Those applicants must qualify for visas through a point system awarding credit for various desirable qualities, such as education, English aptitude, and work experience. Non-EU citizens also face caps on the number of workers admitted even for high-skilled work. Incoming workers must have a job offer in hand, and rules have been tightened on students and family members with non-EU citizenship—even spouses of British citizens aren’t automatically admitted.

There’s little doubt that such rules would shut down the flow of EU citizens into Britain. As much as 90% of the existing EU immigrant workforce, Vargas-Silva estimates, would fail to qualify if the rules were applied to them.

ALSO

Full coverage: Britain votes to leave the European Union

For thousands of Brits, France is home. But what happens after Brexit?

European Union leaders pledge success as a 27-nation bloc, leave Britain’s seat empty

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.