India tries to build a world-class city from scratch, and looks to Singapore for help

- Share via

Reporting from Amaravati, India — On a wide stretch of land bisected by India’s Krishna River, bananas, sugarcane, cotton, guavas and commercial flowers once sprung from dark soil that people described as a farmer’s paradise.

But the leader of the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh saw this as the ideal spot to build a new capital, and in the last four years the land has slowly been transformed.

The crops are nearly all gone now, the farmers having signed over their plots to the state government. Cows meander alongside freshly paved highways, motorized rickshaws haul construction materials instead of crops and giant concrete shells are rising from the earth as the sprawling city of Amaravati takes shape.

Staggeringly expensive and already behind schedule, the city represents India’s biggest attempt at casting off a reputation for urban chaos and pollution and creating a grand, ultra-modern city to match its global ambitions.

Other Indian leaders have sought to put their stamp on the emerging economic power by erecting mammoth statues, demanding eccentric color schemes or clearing slums to create middle-class promenades.

Nothing has matched the scale of Amaravati, which means “abode of the gods.”

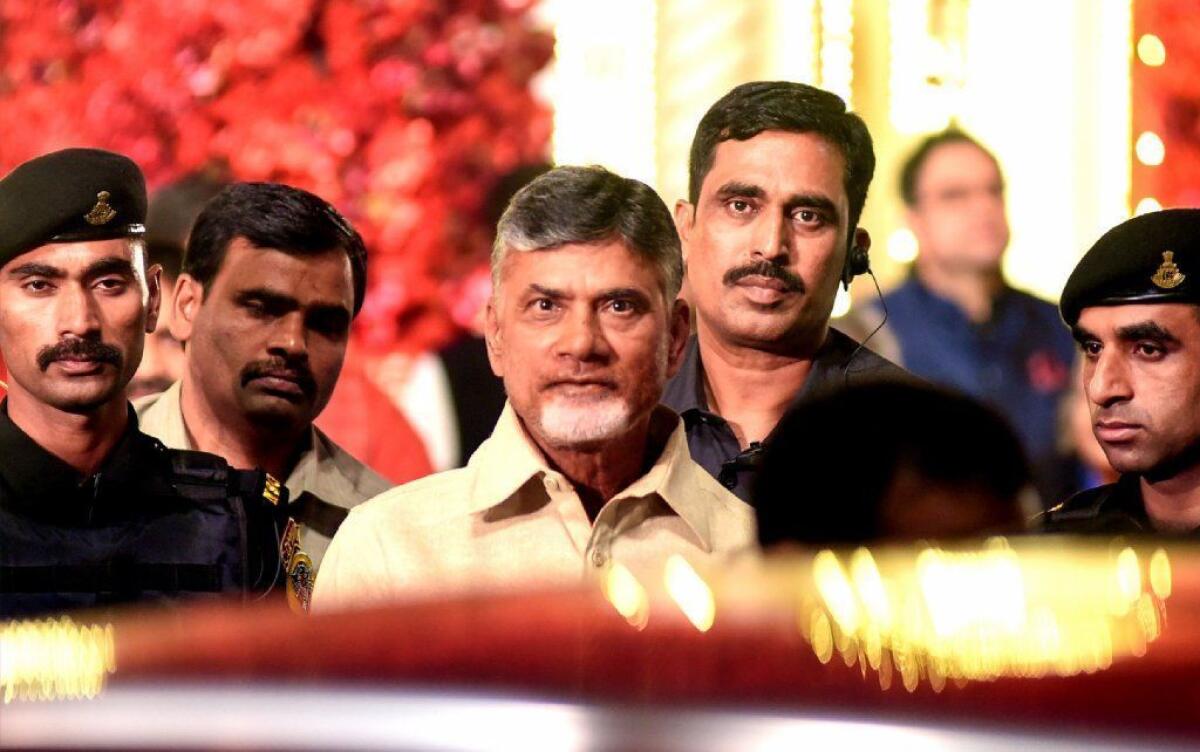

Forced to identify a new capital when the state was divided in 2014, Andhra Pradesh leader Chandrababu Naidu turned to Singapore — Asia’s cleanest and most ruthlessly efficient city — to realize his $15-billion dream. It involves transforming 83 square miles of farmland — about 53,000 acres — into a futuristic cityscape of electric cars, green spaces and landmark buildings, including an assembly chamber shaped like a giant upturned funnel.

Within two decades, he expects the city, which had just 13,000 people in 2011, to house more than 11 million.

Perhaps most fantastical – in a country where urban commuters can often watch most of a three-hour Bollywood movie on their phones before reaching the office – Naidu says his new master-planned capital will place almost every employee within a 15-minute walk to work.

“I’m confident that we will build the best capital in India,” Naidu said this year. “Tomorrow, all over the world, people will talk about Amaravati.”

Some critics call the dream a land grab that will benefit developers over ordinary citizens. Others say attempting to build a city of this size from scratch in India’s raucous democracy – with competing political power centers and a long record of mismanaging major infrastructure projects – is an epic folly.

Naidu has only fueled detractors with claims that, by 2050, Amaravati will be “the best destination in the world for technology, infrastructure and also human resource development.”

Mallela Seshagiri Rao, a farmer and activist who opposes the project, said Naidu ignored a government-appointed expert panel that advised against placing the capital on “some of the best agricultural lands in the country.” Some farmers have said they were coerced into giving up their lands under a “land pooling” program that promised them smaller, developed plots in the new city.

“They have turned productive farmers into land speculators,” Rao said. “This was a green belt producing rice and vegetables for many other states. If you create another concrete jungle, where will that agriculture come from?”

But Naidu from the start was seduced by the idea of a river running through Amaravati, like the cities he has listed as his models: Amsterdam, Venice, Tokyo, Singapore.

The 68-year-old chief minister, who cloaks his marketer’s zeal in simple, khaki-colored safari suits, touts his record in turning the onetime backwater city of Hyderabad, 800 miles south of New Delhi, into an information-technology hub starting in the late 1990s. Companies such as Microsoft and Oracle set up shop in a high-tech enclave outside the city that Naidu dubbed “Cyberabad.”

In 2014, Andhra Pradesh was split into two, and Hyderabad became the capital of the new state, Telangana. Naidu, who had been voted out of office as chief minister a decade earlier, returned as chief minister of the new, smaller Andhra Pradesh, bereft of its largest city – and his crown jewel.

“If you changed the face of a city, brought in foreign investors, it’s an emotional thing for that to be snatched from you,” said Tejaswini Pagadala, author of an appreciative 2018 biography of Naidu. “I think he was looking to create a new legacy.”

Around the world, purpose-built capitals – from Washington, D.C., to Brasilia in Brazil and Naypyidaw in Myanmar – have had mixed success. Building a new city on vacant land is especially tempting in India, where metropolises like Mumbai, Bangalore and New Delhi – itself a master-planned capital designed by the British architect Edwin Lutyens – are vortexes of traffic, endless concrete and failing public services.

Amaravati’s planners say the city will use an extensive network of expressways, arterial roads, water taxis and mass transit. Where most Indian cities have spaghetti-like jumbles of exposed electrical cables and open sewers that must be cleaned by hand, utility cables and sewage lines in Amaravati will run underground.

“Everywhere in India, development came first and infrastructure later,” said Sreedhar Cherukuri, head of the Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority. “We want to reverse this in Amaravati. Whatever is needed for the next 35 years, I want to build it now.”

To create something different, Naidu formed a joint venture with the government of Singapore. Singaporean experts drew up Amaravati’s master plan, and one of the island’s leading urban planning companies, Surbana Jurong, is leading construction on the first of three phases of the city.

“It’s a much more complex political context than ours, but at the end of the day the principles of sustainable development are the same,” said Khoo Teng Chye, executive director of the Center for Livable Cities, a Singaporean government agency involved in the effort.

Naidu has a longstanding fascination with Singapore, but when he visited a few years ago and took in the city’s reclaimed Marina Bay from atop an iconic luxury hotel, Khoo had to temper his excitement.

“I said, ‘Mr. Chief Minister, this is the result of 40 to 50 years of planning,’” Khoo recalled. “It doesn’t happen overnight.”

That is quickly becoming clear in Amaravati, which looks unlikely to meet the 2020 target to complete the first phase of construction.

One brief delay occurred when Indian officials pointed out that Singapore’s first blueprint for the city did not align with vastu shastra, an ancient Hindu system of architecture designed to achieve harmony with nature. The directions of roads and position of some buildings had to be reworked.

In a more significant setback, the World Bank, which had promised a $300-million loan for Amaravati’s construction, has deferred a decision until early next year on whether to launch a formal investigation into farmers’ claims of land grabbing and environmental harm.

Naidu, who faces reelection for another five-year term by May, has linked his political fortunes to his dream capital, and some worry about the project’s fate if he’s ousted from office.

“The way he has envisioned this city, it now comes down to the implementation,” said Pagadala, the author. “Even if it doesn’t come out as 100% of what he planned, it might come up to 50-60%, which is very good for India.”

Shashank Bengali is Southeast Asia correspondent for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @SBengali

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.