Crackdown, arrests loom over Hong Kong as martyrdom becomes part of protest narratives

- Share via

Reporting from Hong Kong — Only four protesters were left in Hong Kong’s legislative chamber as midnight approached.

The rest of several hundred people had finished spray-painting the building, issued their demands to the government and retreated, knowing police were closing in.

At least one of the four remaining protesters had already written a will, according to legislators who were in the room begging them to leave.

Suddenly, several dozen protesters charged back in, chanting, “We leave together! We leave together!”

The chant reflected growing concerns over the safety of demonstrators, some of whom fear that a culture of martyrdom has settled over Hong Kong’s democracy movement.

The protesters dragged the four holdouts out of the chamber. One protester wept as she ran with the group downstairs, telling a local reporter on live television news that they’d come back despite fear of being trapped in the building when police arrived.

“We’re even more afraid that tomorrow we’ll never see the four of them again,” she sobbed. “No one gets left behind.”

Minutes later, armored police squads began firing tear gas and dispersing the crowd outside. When police reached the legislative building, the chamber was clear.

The temporary seizure of Hong Kong’s legislative building late Monday at the end of the 22nd anniversary of the former British colony’s handover to Chinese control took the city by surprise.

It came after hundreds of thousands of peaceful marchers protested an extradition bill that would allow the semiautonomous territory to send suspected criminals to mainland China for trial. Opponents of the bill say it reflects Beijing’s growing influence over Hong Kong.

Leung Kai Chi, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who studies community identity and mobilization, said he and friends were confused by the protesters’ actions at first. There was no legislative meeting taking place at the time.

Then, Leung said, he thought of three protesters who had died in the last two weeks after leaving suicide notes in support of the anti-extradition bill movement. The legislative chamber takeover, he said, appeared to be an extension of such drastic measures.

“There’s a sense of desperation. They don’t know what else they can do,” Leung said.

When police used tear gas and rubber bullets during mass protests on June 12, many of the young people didn’t go home, said local pastor Wong Siu-yung. Four churches had opened their doors to protesters that night, where pastors and social workers had tried to counsel crying, scared demonstrators, many in their teens and 20s.

“They’re sad, they’re lonely, they’re very, very angry. They haven’t sorted out the emotions in their heart,” Wong said. “They don’t want go home, because what do they face? Parents who don’t understand them.”

Some analysts fear that glorification of the recent deaths will have a contagious effect among already emotionally strained protesters. They have tried to prevent dramatization of the suicides, to little avail.

The more protesters made heroes of those who died, the more others suffering mental health problems and feelings of helplessness might try to copy them, misled into thinking their deaths would have meaning, said Paul Yip, director of the Center for Suicide Research and Prevention at the University of Hong Kong.

“These guys like to justify their deaths, and the people use their energy to continue to protest. But these feedback loops are not helpful,” Yip said. “There is no point to use these three cases to anyone’s advantage. We cannot ride on their tragedies to achieve what we want to do.”

Protesters such as Brian Leung Kai-ping, 25, who was among those who charged into the legislative building Monday, disagreed, saying a way to pay respect was to inform others about conditions in Hong Kong.

“If someone sacrificed their life just to make some message heard by other people, I think the correct way to respect and honor them is to spread their message, instead of covering it up,” he said.

By Monday, mental health and martyrdom had become dual themes of the movement.

Along the marching route and at the legislative building complex, candles flickered over white flowers and origami cranes at shrines to the three people who died, often referred to as “martyrs.” Volunteers set up psychological support stations and spread the word about mental health hotlines seeking to prevent suicides. A therapist scrawled her phone number on the ground.

Fernando Cheung, one of several legislators who pleaded with the protesters to remain peaceful before they charged the building and who begged them to leave once inside the chamber on Monday, said one protester told him that if only the demonstrations had done more faster, maybe the three who died might have lived.

“He felt his hand was stained with blood,” Cheung said in an interview.

Cheung had reasoned with the protesters on Monday that storming the building would be counterproductive. It would give the government fodder to label them rioters, he said, which meant potential arrest and up to 10 years in prison.

The group of protesters that wanted to charge told him they knew and accepted the consequences.

Hong Kong’s protests are now famously leaderless. No central leadership also means that small groups can use tactics with which others disagree.

But the protesters have also pledged to support one another despite disagreement over tactics.

“If we argue, then we’re just not a team, and then we will fall…. So we remind each other all the time that we leave no man behind, and we just work toward this,” said Rachael, 24, a protester who asked that her last name not be published for fear of arrest.

She believes in peaceful protest, but went to the legislative building to support those charging in on Monday.

“I totally understand them and I wouldn’t say they are wrong,” Rachael said.

Her parents thought China brought economic benefit to Hong Kong, which Rachael said didn’t matter.

“I’m trying to defend my values. It’s not about how you can bribe me with money or benefits,” she said.

For many, the extradition bill has become a symbol for a deeper, growing sense of helplessness in a political system that prioritizes Beijing’s wishes over citizens’ voices.

China’s central government this week condemned Hong Kong protesters who smashed their way into the legislative chambers, while demonstrators used social media to illustrate their fears of dangerous confrontations with police.

Beijing officials said they supported the Hong Kong government and its police, including an investigation of Monday’s protest and the treatment of some participants as criminals for illegal acts of violence.

Police said Wednesday at least 13 people had been arrested on suspicion of involvement in the pro-democracy protest Monday and face such charges as possession of offensive weapons, unlawful assembly and assault of a police officer.

Legislative Council Chairman Andrew Leung said Tuesday that the legislature’s two remaining meetings before summer recess were canceled.

”Right now LegCo is a big crime scene,” he said to reporters, standing outside the building as police collected evidence inside.

Pro-Beijing legislators in Hong Kong said the damage to the legislative chamber by those who charged the building was stunning.

“No slogan, no demand can justify this violence,” lawmaker Regina Ip said at a news conference.

Legislator Martin Liao dismissed the idea that desperation could justify the legislative building takeover.

“Are you saying desperation is enough to kill people?” Liao said. “We have no sympathy.”

Pro-democracy legislators outside the building Tuesday said that they didn’t condone vandalism, but also appealed to the public to try to understand the desperation felt by some protesters.

Legislator Claudia Mo asked protesters to drop their martyr mentality.

“It’s not worth it,” Mo said. “Time is always on the young’s side.”

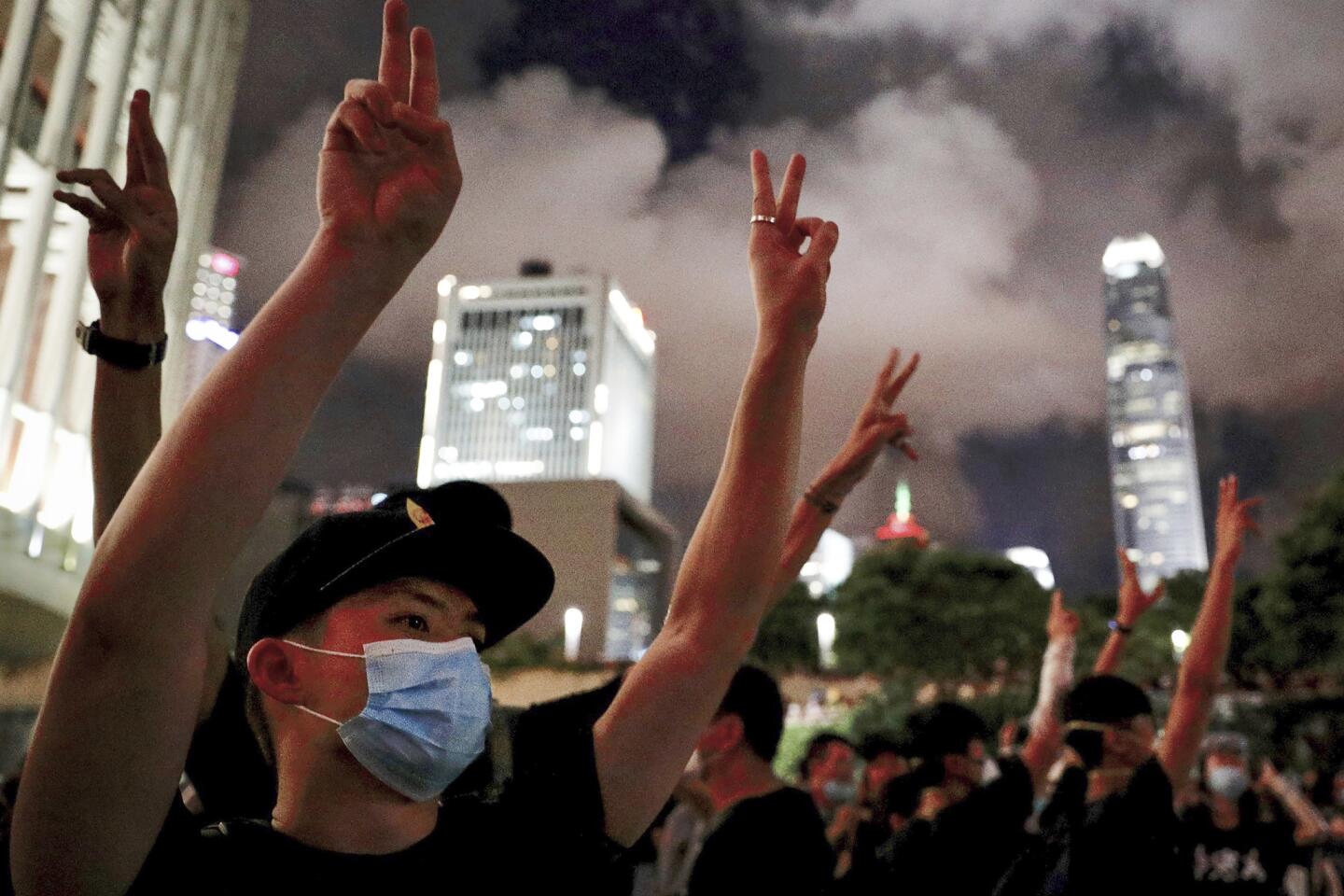

Some observers sympathized with protesters, especially after seeing images such as that of protesters dragging their comrades out of the legislative chamber in apparent attempts to protect them from potential harm.

Anson Chan, a former chief secretary of Hong Kong, said that violence “doesn’t solve anything,” but that Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam and the government should take responsibility for the “increasing sense of anger, futility and frustration.”

“It is the culmination of several years of injustice: a legislative council that is not performing its function; a government that listens only to pro-Beijing parties and ignores the rest of Hong Kong people,” Chan said.

“If you do not address the fundamental problem, which is the disconnect between the government and the vast majority of Hong Kong people, particularly the younger generation — the more you turn a blind eye to their requests, you’re not going to engender trust,” Chan said. “Without trust, Ms. Carrie Lam is going to find it increasingly difficult to govern Hong Kong.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.