No laughing matter: China’s media regulators ban puns

- Share via

Reporting from Beijing — It just got a little less fun to be a headline writer in China.

China’s media regulators have put out a new edict to copywriters, directing them to keep their groaners to themselves.

It’s no laughing matter – the State General Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television issued an order restricting puns and irregular wordplay on television and in advertising.

The order, listed on the media regulator’s website late last week, says that puns could mislead young readers and make it more difficult to promote traditional Chinese culture.

Puns are ubiquitous in Chinese, which has countless homophones. Substituting one character for another can easily change the meaning of a phrase while barely altering the sound.

The Internet age has ushered in a new golden era for wordplay, with many online writers and commentators finding clever ways to mimic or alter traditional four-character idioms.

But the regulator warns that this can result in “cultural and linguistic chaos.” The agency says it now requires compliance with the standard use, phrasing and meanings of characters and idioms.

One example, given in the statement, noted that an advertisement had changed a single character in a standard four-character idiom that means “brook no delay,” altering its meaning to “coughing must not remain.”

The order is particularly strong regarding these idioms, which the regulator declared to be “one of the great features of the Chinese language.”

It also strongly criticized new idioms coined on Internet forums.

“The big difference in the Internet age is that the people who have the privilege of creating puns and idioms have changed,” said Wang Xiaoyu, the former dean of the School of Communications at East China Normal University.

“It is no longer restricted to the elites or the well-educated who can play with the words and come up with puns. A migrant worker, or even a elementary student who knows how to use a computer, can join the conversation online and create his or her own puns,” she said.

Popular sayings and jokes in China rely on wordplay, making it an effective way to connect with an audience. During Lunar New Year celebrations marking the Year of the Horse, it was common to see money stacked on plush horses. “On horseback” can also mean “immediately,” creating a pun meaning “get rich now.” This type of wordplay dates back centuries.

An entire new lexicon of puns has been used online to discuss or lampoon sensitive topics or people. The term for “river crabs,” for instance, echoes the word for “harmony,” a common euphemism for censorship.

The attempt to ban puns comes as China’s government is stepping up control over the media and launching a new push to inculcate “traditional” values.

Last month, the chairman of the regulation bureau, Cai Fuchao, complained that most of the content for television, movies and publications created in China is “rubbish” and recommended concentrating on uplifting social values.

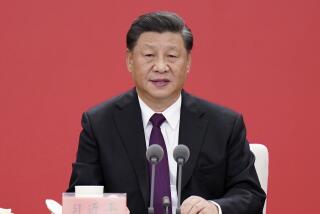

President Xi Jinping echoed this in a speech to television and film luminaries, asking that art, among other things, “uphold the Chinese spirit.”

Even so, it seems unlikely that blocking puns will have any serious long-lasting effect.

“Maybe in the short term, no one wants to be the one [to flout] the government’s new rule,” said Wang. “But I don’t think the rule can stop similar tweaking of words to be used in future commercials.”

Silbert is a special correspondent. Tommy Yang of The Times’ Beijing Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.