U.S. airstrikes rise sharply in Afghanistan — and so do civilian deaths

- Share via

As U.S. warplanes flew above a cluster of villages where Islamic State militants were holed up in eastern Afghanistan, 11 people piled into a truck and drove off along an empty dirt track to escape what they feared was imminent bombing.

They did not get far.

An explosion blasted the white Suzuki truck off the road, opening a large crater in the earth and flipping the vehicle on its side in a ditch. A teenage girl survived. The 10 dead included three children, one an infant in his mother’s arms.

The lone survivor of the Aug. 10 blast in Nangarhar province, and Afghan officials who visited the site, said the truck was hit by an American airstrike shortly before 5 p.m. Relatives expressed horror that U.S. ground forces and surveillance aircraft could have mistaken the passengers, who included women and children riding in the open truck bed — in daylight with no buildings or other vehicles around — for Islamic State fighters.

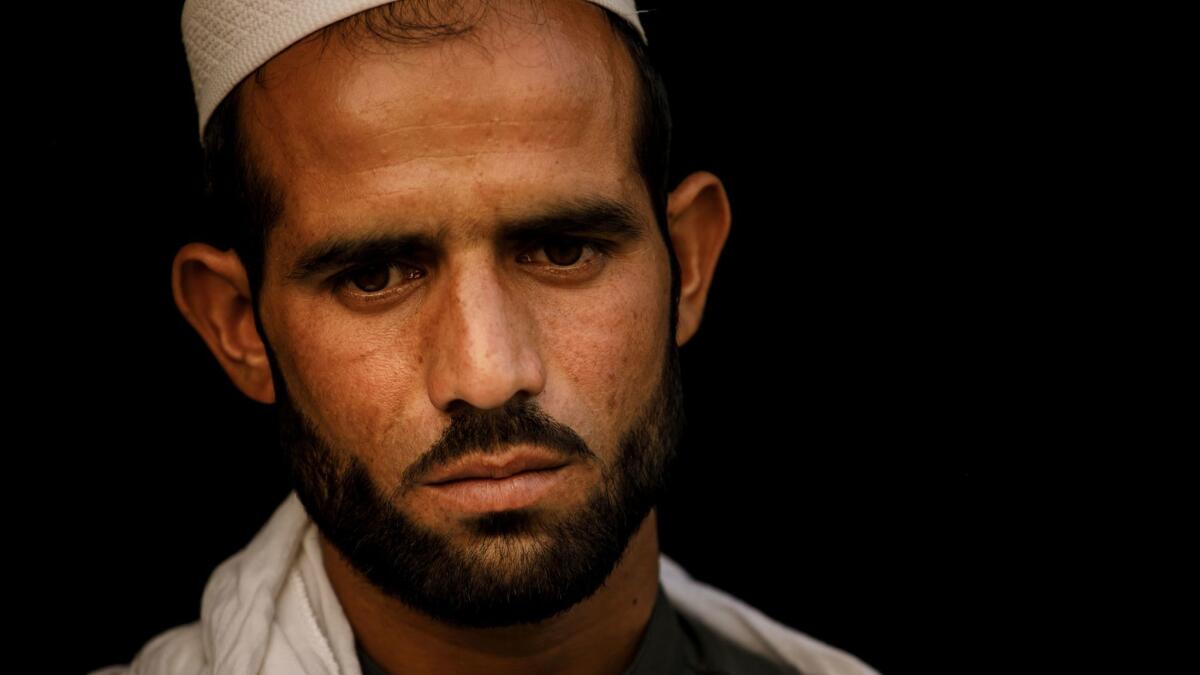

“How could they not see there were women and children in the truck?” said Zafar Khan, 23, who lost six family members, including his mother and three siblings, in the blast.

In a statement after the incident, the U.S. military acknowledged carrying out a strike but said it killed militants who “were observed loading weapons into a vehicle” and “there was zero chance of civilian casualties.”

Pockets of Nangarhar remain inaccessible to outsiders because of fighting, making it impossible to independently determine the cause of the fatal explosion. What is not in question is that in the 17th year of U.S. military involvement in Afghanistan, American airstrikes are escalating again, along with civilian casualties.

Operating under looser restrictions on air power that commanders hope will break a stalemate in the war, U.S. fighter planes this year dropped 3,554 explosives in Afghanistan through Oct. 31, the most since 2012.

American officials say the firepower has curtailed the growth of Islamic State’s South Asia affiliate — known as ISIS-Khorasan, which they believe numbers about 900 fighters, most of them in Nangarhar — and enabled struggling government forces to regain ground against Taliban insurgents in other provinces, such as Helmand, where a Marine-led task force has helped coordinate a months-long offensive.

But innocent Afghans are asking: At what cost?

The United Nations mission in Afghanistan documented 205 civilian deaths and 261 injuries from airstrikes in the first nine months this year, a 52% increase in casualties compared with the same period in 2016. Although both U.S. and Afghan forces conduct aerial attacks, preliminary data indicate that American strikes have been more lethal for civilians.

In the first six months of 2017, the U.N. said, 54 civilians died in international air operations, compared with 29 in Afghan strikes. Twelve additional deaths could not be attributed to either force, the U.N. found.

In the case of the blast in Nangarhar province in August, U.S. officials have continued to assert that the American airstrike that day struck only militants. But they have since offered an alternative explanation for the civilian deaths. Responding to questions from The Times, coalition officials said that a passenger vehicle — presumably the Suzuki truck — hit a roadside bomb planted by Islamic State militants slightly more than a mile from where the airstrike killed the militants. It was the roadside bomb that resulted “in multiple enemy-caused civilian casualties,” said Navy Capt. Tom Gresback, a spokesman for coalition forces in Kabul.

Afghans vigorously dispute that account. The district police chief, Hamidullah Sadaqat, said there was only one deadly explosion in the area that afternoon. Rozina, the 17-year-old survivor, said her memory was clear.

“The plane dropped the bomb on us,” said Rozina, who, like many Afghans, has only one name.

How could they not see there were women and children in the truck?

— Zafar Khan, who lost six family members in the Aug. 10 bombing

The bombing occurred in Haska Mina district, about three hours by road south of the provincial capital, Jalalabad. The victims were residents of Loi Papin, a village near the front line between government-controlled territory and the Islamic State-held village of Gorgoray.

Many left Loi Papin more than two years ago after militants arrived claiming allegiance to Islamic State. The extremists tortured locals and barked orders from mosque loudspeakers, demanding that families surrender adult sons to their ranks.

Khan, a slender laborer with close-set eyes, fled to a rented house on the outskirts of Jalalabad. Other family members made brief trips to Loi Papin to tend to their farm and flock of sheep, he said.

On the afternoon of Aug. 10, Khan’s mother, Malaika, left the village with three of her 10 children — 12-year-old Bahadur Shah, 8-year-old Anisa and 1-year-old Mohammad — in the Suzuki truck, driven by his cousin. His uncle was on board as well as five others, including Rozina, her father and brother, who were returning to a house they had rented in the district center, still under government control.

“Everyone was trying to get away,” Khan said. “We had recently sold our sheep and half the land. It was too dangerous to be in the village. No one wants to be anywhere close to Daesh” — a colloquial term for Islamic State.

Rozina said everyone in the truck was “afraid of the Americans.”

“Because we knew they were in the area,” she said, “we expected that they would bombard by the next day.”

As they drove off, she recalled seeing two planes in the sky. Then the blast struck, knocking her unconscious for several minutes. When she awoke, she found that seven people were dead, including her father and brother.

Malaika and two of her children were badly wounded and yelling for help, Rozina said. But American troops in the area — probably U.S. special operations forces conducting joint operations with Afghan commandos against Islamic State — did not allow anyone to come to their aid for hours, she said.

“They died because there was no one to help them,” Rozina said. “They were stuck and screaming.”

Khan and several others set off from Jalalabad after the bombing, reaching Haska Mina in the middle of the night. They found the crumpled truck overturned in a field. Rozina was lying at a woman’s house with severe injuries to her face, hands and legs. Villagers had carted the bodies away in wheelbarrows and brought them to a nearby mosque.

“I found a piece of a leg and a thumb next to the truck,” said Mohammad Agha, 42, whose cousin, a peanut farmer also named Khan, was among the dead.

Sadaqat, the district police chief, took Agha and other family members to a former Afghan Border Police base being used by U.S. special operations troops. Speaking through an Afghan interpreter, the Americans gave the relatives until noon to bury the bodies. They worked quickly, Agha said; Islamic custom requires bodies to be interred within 24 hours, wrapped in simple shrouds.

“We didn’t have enough fabric to cover them all properly,” he said. “We had to use shawls.”

When they were done, Agha and others went to inform the Americans, who dismissed the possibility that a U.S. plane had launched the strike.

“They said maybe it was a mortar fired by Daesh, but a mortar wouldn’t have created a 10-foot crater,” Agha said. “The Americans asked us: ‘Which country’s plane did this?’ It seemed like they weren’t taking us seriously so we left.”

When there were 100,000 American troops in the country, then-President Hamid Karzai frequently accused them of excessive force and wielded reports of dead innocents as a cudgel against the United States. Karzai’s bombast had an effect: Far fewer civilians died in airstrikes in 2012 and 2013, according to U.N. reports, when the U.S. averaged hundreds of airstrikes a month.

Experts said North Atlantic Treaty Organization coalition commanders took serious measures to reduce the risk of harm to civilians. They met regularly with the U.N. and nongovernmental agencies and dedicated a team of officers to investigate complaints.

As the foreign troop presence shrank and NATO shifted its focus to training Afghan forces, coalition officials released less information about operations. They also face less resistance from Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, a stronger proponent of U.S. military action.

“The U.S. military is becoming less transparent, and it’s a pity because they had worked really hard — and succeeded — in reducing civilian casualties,” said Kate Clark, co-director of the Afghanistan Analysts Network, a Kabul-based research organization.

The use of air power has surged since mid-2016, when the Obama administration approved new rules of engagement that allowed U.S. warplanes to open fire in support of Afghan operations, not just to defend coalition forces. It is expected to rise further after the Trump administration sent nearly 4,000 more troops to Afghanistan — bringing the total U.S. presence to 15,000 — and grants more latitude to military commanders.

U.S. planes carried out 1,570 strikes from August through October, the most in a three-month period since 2012, according to U.S. Air Force statistics.

In October, Defense Secretary James N. Mattis testified to Congress that Trump had authorized him to eliminate the requirement that U.S. forces could fire only when in “proximity” to hostile fighters.

“In other words, wherever we find the enemy, we can put the pressure from the air support on them,” Mattis said. But he added that U.S. forces would still do “everything humanly possible to prevent the death or injury of innocent people.”

Military officers say every report of civilian casualties is investigated. U.S. forces attempt to interview residents and local officials and use “all forensic actions available, based on the security threat,” said Gresback, the military spokesman.

But just as in Iraq and Syria, where the U.S.-led coalition is accused of significantly undercounting the civilian toll of its air war against Islamic State, Afghan victims believe the U.S. military isn’t being thorough or transparent enough.

Rozina and relatives of other victims in Loi Papin said American officials have not contacted them. And the U.S. has often pushed back strongly against accusations that its operations are taking a greater toll on innocents.

In early November, after reports that an airstrike killed 14 civilians in the northern province of Kunduz, American officials said they found “no evidence” to support the claims. That prompted a rare direct challenge from the United Nations, which said in a series of tweets that “interviews with multiple survivors, medics, elders & others give strong reason to believe civilians [were] among [the] victims.”

U.S. forces have also suggested that Afghans in Nangarhar are lying about civilian deaths. The military’s initial statement on the Aug. 10 blast called it “the second false claim of civilian casualties in the same district within the last three weeks” — after an incident in which Haska Mina residents told Afghan media that a U.S. strike killed mourners attending a funeral service.

Although public outrage over civilian casualties has softened, Clark said they continue to serve as a propaganda tool for extremists.

“The basic parameters of the war haven’t changed: If you’re killing civilians, it’s going to be problematic,” Clark said. “The bullish U.S. approach, taking the gloves off, that’s all very well, but if there are more dead civilians you’re not going to be better off politically or militarily.”

Ghani’s government has not drawn attention to the strike in Nangarhar, but officials visited from Kabul and gave families condolence payments of more than $1,000 each.

The money won’t replace the loss of family breadwinners, or cover the mounting medical bills for Rozina. She now lives with four family members at an uncle’s house and walks with crutches while she awaits additional operations to her feet.

Khan said he has little sympathy for Islamic State but cannot support the way the U.S. is prosecuting the war.

“The Americans say they are here to kill terrorists, but if they can’t carry out a proper operation, it is better that they leave us alone,” he said. “At least we would not see our families destroyed.”

Special correspondents Sultan Faizy and Mohammad Anwar Danishyar contributed to this report.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

ALSO

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.