Global Development: These youths in Senegal are supposed to be studying Islam, but many are begging in the streets

- Share via

Reporting from Dakar, Senegal — Ahmadou Cisse rises from his stained, coil-ridden mattress shared with four other youths on a rooftop at about 5 a.m. each day.

The 14-year-old boy walks six miles from the suburbs of Dakar, the capital of Senegal, weaving among traffic and tapping on car windows in the hopes of receiving spare coins or food. He must beg to survive.

“I do not feel safe doing this,” Ahmadou said recently.

The skeleton-thin youth is among tens of thousands of children who line the dusty streets of Senegal pleading for food or money with old tin cans and buckets in hand, according to estimates by UNICEF.

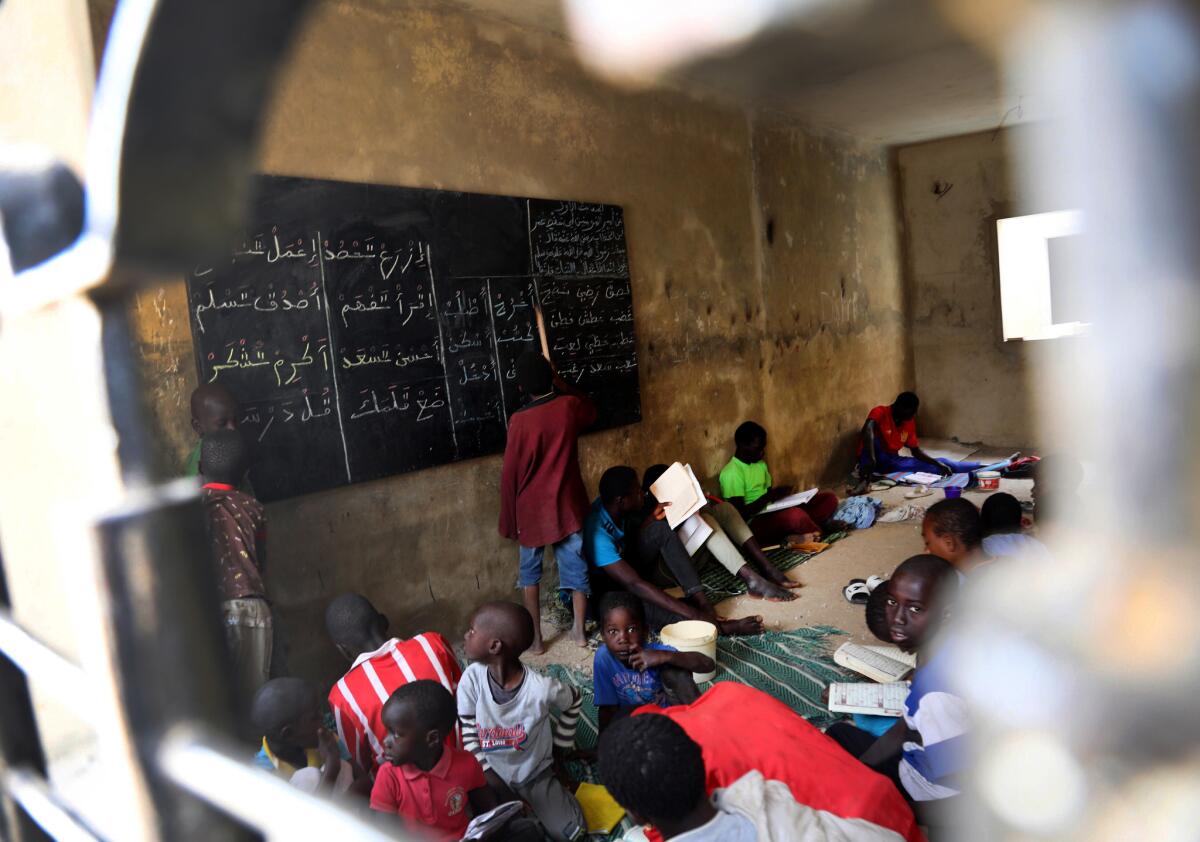

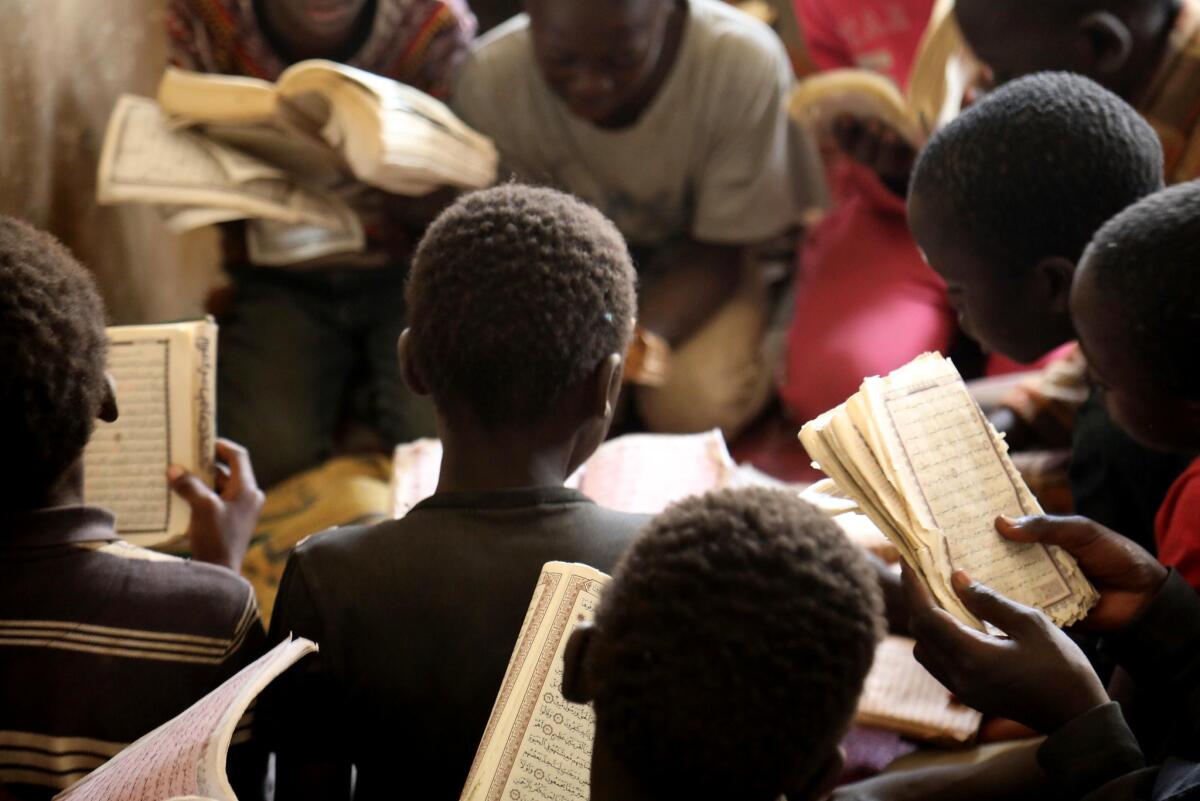

Many of the youths, like Ahmadou, are experiencing what some families consider a traditional Quranic education in which children as young as 2 are sent to religious schools called daaras to memorize Islamic scripture and learn humility. The country is about 95% Muslim.

But a stubborn problem keeping youths at risk involves some teachers known as marabouts forcing youths to fund the destitute daaras through begging, and, at times, resorting to beatings if quotas are not met, according to government officials and human rights agencies. The youths, or talibes, often sleep in crumbling buildings, on roadsides or in shopfronts.

The government has tried to remove children from the streets and protect them from mistreatment — some youths have died from beatings or experienced other tragedies — but its efforts have suffered from insufficient resources, lack of coordination and other problems, Human Rights Watch and others have said.

“Sometimes my marabout will take what I collect and sell it,” said Ahmadou, who comes from a small village in Gambia and has not seen his family for years. “One time when I didn’t bring back enough money he whipped me so hard I couldn’t lie down properly for a week.”

Despite the many problems, officials and activists say that some daaras are honest, legitimate and free from abuse, and some pupils become marabouts or respected imams. The schools, whose roots go back hundreds of years, are often held in high esteem, and leaders have graduated from them.

For those struggling to care for children, daaras provide a free education. The average household in Senegal contains nine people, the largest in the world, according to the U.N., and many people suffer from poverty.

A report by Human Rights Watch expected to be released this month increases its estimate of talibes in Senegal from 50,000 to 100,000 out of a population of 16 million. The capital, Dakar, has at least 30,000 talibes, Saint-Louis has 14,000, and other cities including Thies, Touba and Kaolack have some as well.

Some marabout teachers are trafficking children from countries across West Africa such as Guinea, Mali and Gambia, according to the report’s author, Lauren Seibert. Thousands of children exist as modern-day slaves, vulnerable to physical abuse and neglect. The U.N. estimates that child begging earns $8 million per year for marabouts in Dakar alone; nationwide figures are unknown.

“Exploitation is rife, and some of these schools are so bad that talibes haven’t even memorized the Quran after seven years,” Seibert said. “Some are shackled and beaten regularly. We need regulation of the daaras and for abusive schools to be shut down and held to account.”

Several nonprofit organizations said sexual abuse is endemic within the system. Often perpetrators are elder talibes, but sometimes it can be outsiders.

Issa Kouyate, the president of a charity called Maison de la Gare in the northern city of Saint-Louis, said he first saw one of Senegal’s street children being raped in 2009. A middle-aged man fled as he approached, leaving a 10-year-old boy collapsed and crying.

“He was completely naked outside the bus station, trousers around his ankles,” Kouyate said. “It happens every night that these little boys are sexually abused.”

Alassane Diagne, a project coordinator for Dakar-based Empire des Enfants, a center that provides healthcare and education for up to 90 street children at a time, said malnutrition, dehydration and malaria are also common.

“The children who come to us are often sexually abused, have suffered violence and have psychological problems,” Diagne said.

Abdul Aziz Bah, a marabout based in the Keur Massar suburb of Dakar who is responsible for 100 children, condemned the abusive teachers as charlatans.

“Talibes are a Senegalese tradition, but there are some who exploit the children,” he said, amid a racket of Quranic recitation from pupils in the background. “They are different from daaras. They are fake daaras.”

Some activists and other observers said the government has failed to effectively combat the exploitation tied to talibes.

The U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child has condemned the “very low rate of investigations, prosecutions and convictions of those responsible for trafficking, forced begging, child prostitution or forced child labor” in Senegal.

In 2005, the Senegalese government passed a law prohibiting forced begging, which if violated could result in up to five years in prison. It was implemented in 2010 when seven marabouts were convicted. They received six-month suspended sentences and a $171 fine each. None went to prison.

In 2016, the government ordered the removal of children from the streets, and around 500 in Dakar have been placed in transit centers and returned to their parents. But there were no accompanying investigations or prosecutions.

A draft law to set standards and regulations for daaras was approved by the country’s Council of Ministers in June 2018. The Assn. of Senegalese Jurists called for the immediate adoption of the draft law “to protect children” this year in an open letter ahead of elections, which resulted in President Macky Sall winning a second term, but there has been no move in the National Assembly to pass it.

“We are doing everything that we can to protect these children,” said Alioune Sarr, head of child protection in the Senegalese government.

Children’s centers and social services offices are overwhelmed and receive minimal resources, he said. As a result, the care and legal assistance the children desperately need is not provided.

“It’s a human catastrophe,” said Souleymane Diagne, a social worker in Dakar’s Medina neighborhood.

Yeung is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.