From jail, drug lord ‘El Mayo’ Zambada tells wild story of corruption and murder

- Share via

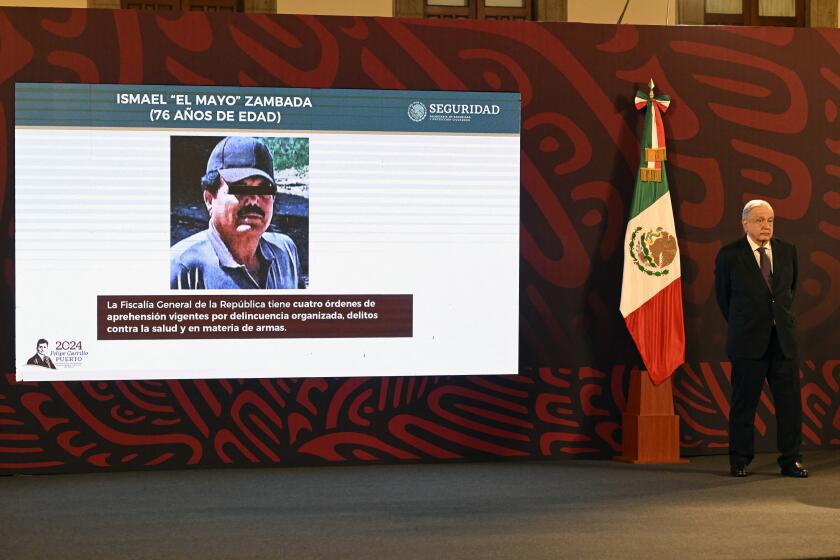

The reclusive drug kingpin Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada was famous for staying out of the public eye, ruling a multibillion-dollar narcotics trafficking empire from remote mountain hideouts and speaking to the press just once over the course of his decades-long criminal career.

But on Saturday, Zambada thrust himself into the spotlight, issuing a remarkable statement from jail in the United States, where he is being detained after an alleged betrayal by another cartel trafficker seeking to cut a deal with authorities.

In a two-page document in English sent to The Times by his attorney, Frank Perez, the Sinaloa cartel leader said he was kidnapped by the son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, flown to a small airport near El Paso and handed over to authorities. He claimed that a prominent politician in Sinaloa was killed in the process.

Zambada, 76, the cartel’s co-founder, was long believed to have police, soldiers and political leaders in his pocket. But the new statement includes unprecedented admissions of those ties. He described how a state police official served as his personal bodyguard and said he had agreed to leave his hideout at the request of 38-year-old Joaquín Guzmán López to “help resolve differences” between two feuding politicians.

Those politicians, he said, were Sinaloa Gov. Rubén Rocha Moya and Héctor Melesio Cuén Ojeda, a former mayor of the state capital, Culiacán.

Zambada said Cuén Ojeda was shot dead at the meeting. That’s a different version of events than one shared by Sinaloa law enforcement authorities, who said they believed Cuén Ojeda had been killed in an attempted carjacking.

“I am aware that the official version being told by Sinaloa state authorities is that Héctor Cuen was shot in the evening of July 25th at a gas station by two men on a motorcycle who wanted to rob his pick-up truck,” Zambada said. “That is not what happened. He was killed at the same time, and in the same place, where I was kidnapped.”

Perez said he released Zambada’s statement “to set the record straight and counter the false narratives.”

Zambada said the two Sinaloa politicians were locked in a dispute “over who should lead” the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, where Cuén Ojeda, a onetime candidate for governor, had once been the rector.

At a news conference Saturday, Rocha forcefully denied any knowledge of the meeting described by Zambada, saying he was not in the state on the day it allegedly occurred. “We have not been complicit with anyone,” he said.

Zambada has pleaded not guilty to federal charges in El Paso. The Justice Department is expected to transfer his case to Brooklyn, N.Y., where he also faces charges, to the same court that hosted the trial of El Chapo, his longtime partner who is serving a life sentence in the U.S. after a 2019 conviction.

There is growing evidence to suggest Ismael ‘El Mayo’ Zambada was hauled against his will from Mexico to El Paso in an effort by El Chapo’s son to curry favor with U.S. authorities.

El Chapo’s son, Guzmán López, has pleaded not guilty to federal charges in Chicago, where he and his younger brother Ovidio are accused of leading a cartel faction, Los Chapitos, known for manufacturing and exporting illicit fentanyl. Their lawyer, Jeffrey Lichtman, did not immediately respond to a request for comment Saturday and has previously denied that the elder Guzmán López sibling had struck a deal to cooperate with U.S. authorities.

In his statement, Zambada said he arrived early for a meeting scheduled for 11 a.m. at a ranch and event center called Huertos del Pedregal, just outside Culiacán. He said he also expected to see Iván Guzmán Salazar, an older half-brother of Guzmán López who remains a fugitive in Mexico, wanted for co-leading Los Chapitos.

“I saw a large number of armed men wearing green military uniforms who I assumed were gunmen for Joaquín Guzmán and his brothers,” Zambada said.

Zambada said he brought his own bodyguards, including José Rosario Heras López, a commander in the State Judicial Police of Sinaloa, and Rodolfo Chaidez, whom he described as “a longtime member of my security team.”

“While walking toward the meeting area, I saw Héctor Cuen and one of his aides. I greeted them briefly before proceeding inside to a room that had a table filled with fruit,” Zambada said. “I saw Joaquín Guzmán Lopez, whom I have known since he was a young boy, and he gestured for me to follow him. Trusting the nature of the meeting and the people involved, I followed without hesitation. I was led into another room which was dark.”

Zambada continued: “As soon as I set foot inside of that room, I was ambushed. A group of men assaulted me, knocked me to the ground, and placed a dark-colored hood over my head. They tied me up and handcuffed me, then forced me into the bed of a pickup truck.”

Zambada said he was “subjected to physical abuse, resulting in significant injuries to my back, knee and wrists,” and driven to a landing strip “about 20 or 25 minutes away, where I was forced onto a private plane.”

He said that once on board the airplane, Guzmán López removed the hood and “bound me with zip ties to the seat.”

Photos taken by U.S. news media inside the plane after it landed showed a bag from the Mexican gas station chain Oxxo containing zip ties, along with cookies and snacks.

Zambada said the two bodyguards who were with him, including the state police official, have been missing since the ambush. The statement said Cuén Ojeda was killed at the scene and that his body was taken away.

“The notion that I surrendered or cooperated voluntarily is completely and unequivocally false,” Zambada said. “I was brought to this country forcibly and under duress, without my consent and against my will.”

Mexican officials have said the Guzmán López brothers reached an agreement to cooperate with U.S. authorities in hopes of receiving leniency in their cases, which could carry long prison sentences.

A spokesperson for the Department of Justice did not immediately respond to a request for comment Saturday morning.

Zambada, should he choose to cooperate with U.S. authorities, could spill more than 40 years of secrets about whom he and his cartel have corrupted in Mexico. Twice during criminal trials in the United States, allegations have surfaced that the Sinaloa cartel made payments to an early and unsuccessful presidential campaign by Andrés Manuel López Obrador in 2006. The president, who was elected when he ran again in 2018, has vehemently denied any links to drug traffickers.

With a president-elect from his own party, Claudia Sheinbaum, poised to replace him in October, López Obrador called this week for Zambada and Guzmán López to reveal whatever they might know about political corruption in Mexico to U.S. investigators.

“If they can tell how much support was given to authorities, if they can inform on who was protecting them, all of that will help a lot, and also their agreements with the U.S. agencies. … Make it all transparent. That would help a lot,” the president said at a news conference.

López Obrador and Sheinbaum were scheduled to appear Saturday in Sinaloa at the opening of a hospital. The president and president-elect are from the same political party as Rocha, the Sinaloa governor.

State authorities in Sinaloa have said Cuén Ojeda was declared dead by doctors at a private clinic in central Culiacán on the night of July 25. An autopsy showed he died from the impact of four bullets, one of which hit a major artery on his right leg.

Sinaloa Atty. Gen. Sara Bruna Quiñonez Estrada said in a statement last week that police are investigating “all possible causes” in Cuén Ojeda’s case.

Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada’s lawyer denies that his client was merely tricked into boarding an aircraft to the U.S., saying the captured drug kingpin was “forcibly kidnapped.”

“The State Attorney General’s Office does not rule out any line of investigation … and continues to carry out all relevant investigative acts to clarify the facts and bring those responsible to justice,” Bruna said.

Zambada called for “the truth to come out” about the events of July 25.

“I call on the governments of Mexico and the United States to be transparent and provide the truth about my abduction to the United States and about the deaths of Héctor Cuen, Rosario Heras, Rodolfo Chaidez, and anyone else who may have lost their life that day,” he said. “I also call on the people of Sinaloa to use restraint and maintain peace in our state. Nothing can be solved by violence. We have been down that road before, and everyone loses.”

Sinaloa authorities said the man who brought Cuén Ojeda to the Culiacán clinic reported that the shooting had occurred in a failed carjacking attempt at a gas station.

The witness reportedly said a gas station attendant was fueling Cuén Ojeda’s truck when two men on a motorcycle ordered him out of the vehicle. After Cuén Ojeda refused to comply, officials said, the men shot him and sped off.

Two gas station employees interviewed by journalists for the local news site Ríodoce said that they did not see a motorcycle approach the vehicle or see an altercation.

Ken Salazar, the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, released a statement Friday that said Guzmán López surrendered to U.S. authorities voluntarily and that “the evidence at the moment indicates El Mayo was brought against his will.”

Salazar said no U.S. resources were used in the “rendition” of Zambada: “It was not our plane, not our pilot, and not our people.”

Salazar said U.S. authorities did not receive a flight plan for the plane in advance, and that the plane took off somewhere in Sinaloa, contradicting previous statements from Mexican officials that said the craft disembarked from Hermosillo in the neighboring state of Sonora.

A prominent figure in Sinaloa, where his leadership of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa earned him the affectionate nickname “El Maestro,” Cuén Ojeda pivoted from an academic career to politics in 2010, later forming his own party. He also ran for Senate and served as state secretary of health until 2022.

A statement released by Cuén Ojeda’s family remembered “his tireless commitment to work, his hand always outstretched to help others and the big heart that he always had open to those around him.”

The family’s statement made “a firm and respectful call” for the case to be investigated “free of any speculation to provide the justice that his work and legacy have left us in his time in this life and that he rightly deserves.”

Former federal prosecutors have told The Times that even if it’s true that Zambada was kidnapped and other crimes occurred as he was brought to the United States, it’s unlikely that the charges against him will be dismissed due to a violation of Mexico’s extradition treaty or for other procedural reasons.

In 2019, the Mexican government forced the return of Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos, a former defense secretary who had been arrested that year on narco-corruption charges by the Drug Enforcement Administration while traveling to the U.S. with his family.

López Obrador was furious about the general’s arrest, arguing that the country’s sovereignty had been violated. The Justice Department ultimately dropped all charges and allowed Cienfuegos to return home. Mexican authorities later released evidence from the case and maintained the general was innocent.

There is some evidence to support Zambada’s claims that he was in league with corrupt Mexican officials. During the trial of El Chapo in Brooklyn in 2019, Zambada’s eldest son, Vicente Zambada Niebla, testified that the cartel paid an estimated $1 million per month in “salaries” to officials at all levels of government. Zambada Niebla testified that a commander of the state judicial police, the agency his father mentioned in his statement Saturday, would receive around $50,000 per month.

State police commanders were given the nickname “Yankee,” Zambada Niebla testified, and his father liked to hand-deliver the bribes.

“My dad is the kind of person who liked to see the Yankees or commanders personally,” he said.

Zambada Niebla also detailed payments on his father’s behalf to a military general, federal police officials, and agents from the Mexican attorney general’s office tasked with investigating organized crime.

Amid eroding trust between the U.S. and Mexico on security issues, Mexican officials were caught off guard by the arrest of Sinaloa cartel leaders Ismael ‘El Mayo’ Zambada García and Joaquín Guzmán López.

Tim Sloan, former head of the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in Mexico, noted that López Obrador was once photographed shaking hands with El Chapo’s mother in Sinaloa, a gesture that did little to quiet speculation about the president’s sympathies.

Pushing to return Zambada, Sloan said, would be untenable: “It would be really bad politically for Mexico to go out on a limb for this guy who has been one of America’s most wanted for decades.”

Hamilton reported from San Francisco and Linthicum from Mexico City. Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico City contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.