- Share via

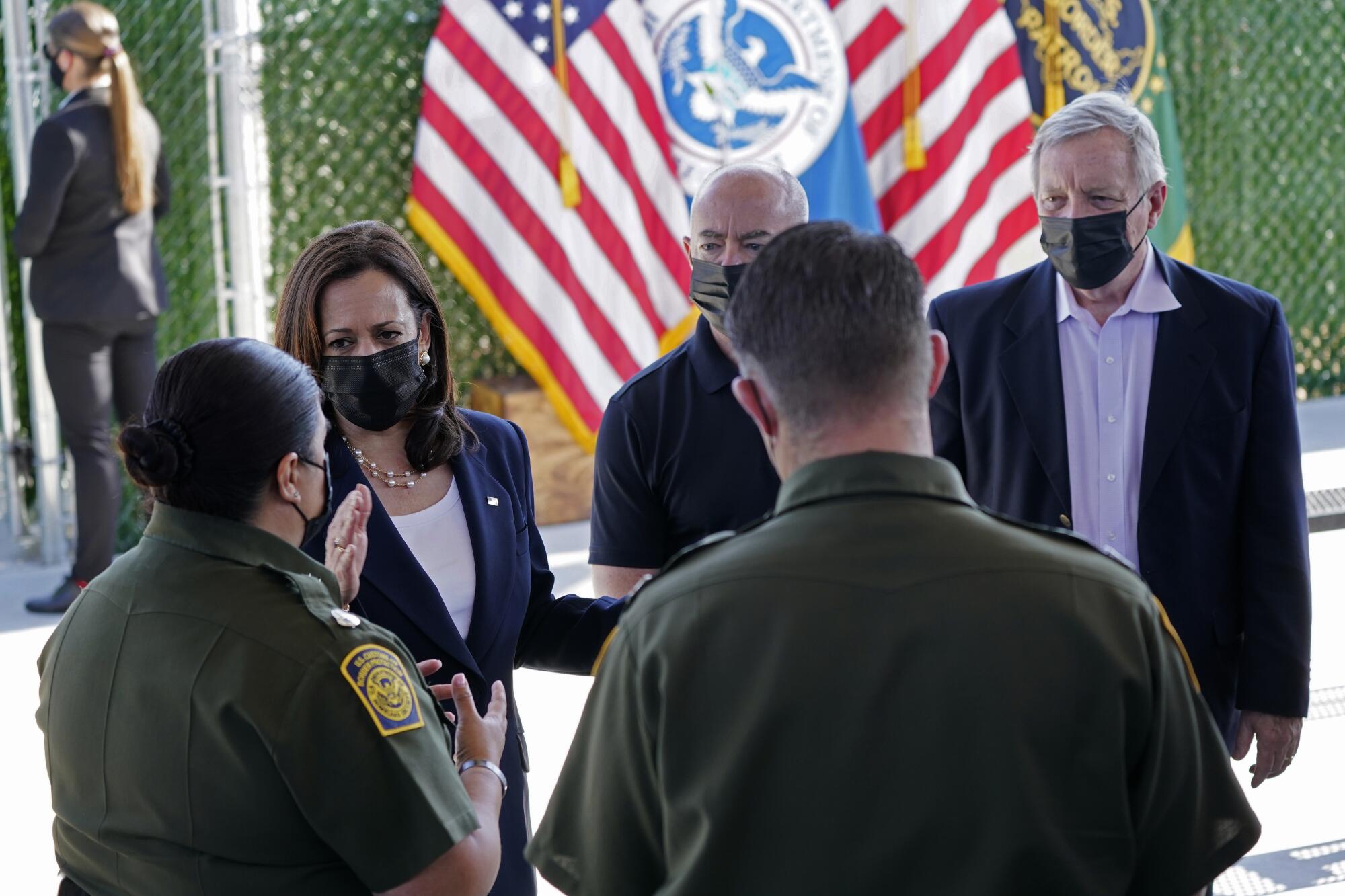

MEXICO CITY — Speaking in Guatemala City on her first foreign trip as vice president, Kamala Harris issued a stern message to Central Americans.

“I want to be clear to folks in this region who are thinking about making that dangerous trek to the United States-Mexico border,” she said. “Do not come. Do not come.”

Her 2021 remarks were widely scorned by rights advocates as arrogant and out of touch with the complex mix of poverty, violence and other factors that drives people to leave their countries. Later, as border crossings surged, Harris’ words would be mocked by Republicans as evidence that the Biden administration had no plan when it came to halting migration.

Immigration experts say the Biden administration picked the wrong immigration strategy, choosing a plan that failed to anticipate the shifting nature of migration.

The episode underscored the political pitfalls of an issue expected to play a key role in this year’s presidential race — and the formidable nature of the foreign policy portfolio that Harris had taken on at President Biden’s request: addressing the root causes of migration from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

It was an unwinnable assignment that Harris never wanted. And while she claimed some accomplishments — including coaxing private companies to pledge billions of dollars of investment in Central America — she was criticized as showing tepid interest in the issue and for visiting Latin America just twice.

“It was promising at first, but then disappointing,” said a Mexican official who met with Harris in 2021 when she and Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador signed an agreement to forge new development programs in Central America.

Harris grew distant after the summit and stopped attending meetings, said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity: “She quit.”

Now that she is the leading Democratic presidential candidate, Harris is facing renewed scrutiny over her record in the White House and her views on immigration more broadly.

Harris was never in charge of immigration enforcement or border policy. But that hasn’t stopped Republicans from painting her as a failed “border czar” who is to blame for a record surge in unauthorized migration under Biden.

“Let me remind you: Kamala had one job. One job. And that was to fix the border,” Nikki Haley, the former governor of South Carolina who ran for the GOP presidential nomination this year, said at the Republican National Convention this month. “Now imagine her in charge of the entire country.”

As for those on the left disappointed that Harris hasn’t been a stronger defender of migrants, some acknowledge that would be difficult in the current political climate, where concern over immigration has become a top issue for voters.

More migrants illegally enter the United States along this California stretch of the border than anywhere else. They’re not coming from the places you’d expect

Angelica Salas, the executive director of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, has known Harris for decades and said her comments in Guatemala belied a track record of standing up for migrants earlier in her political career.

“Why have you been put up to say this?” Salas remembers thinking. “This is not who you are.”

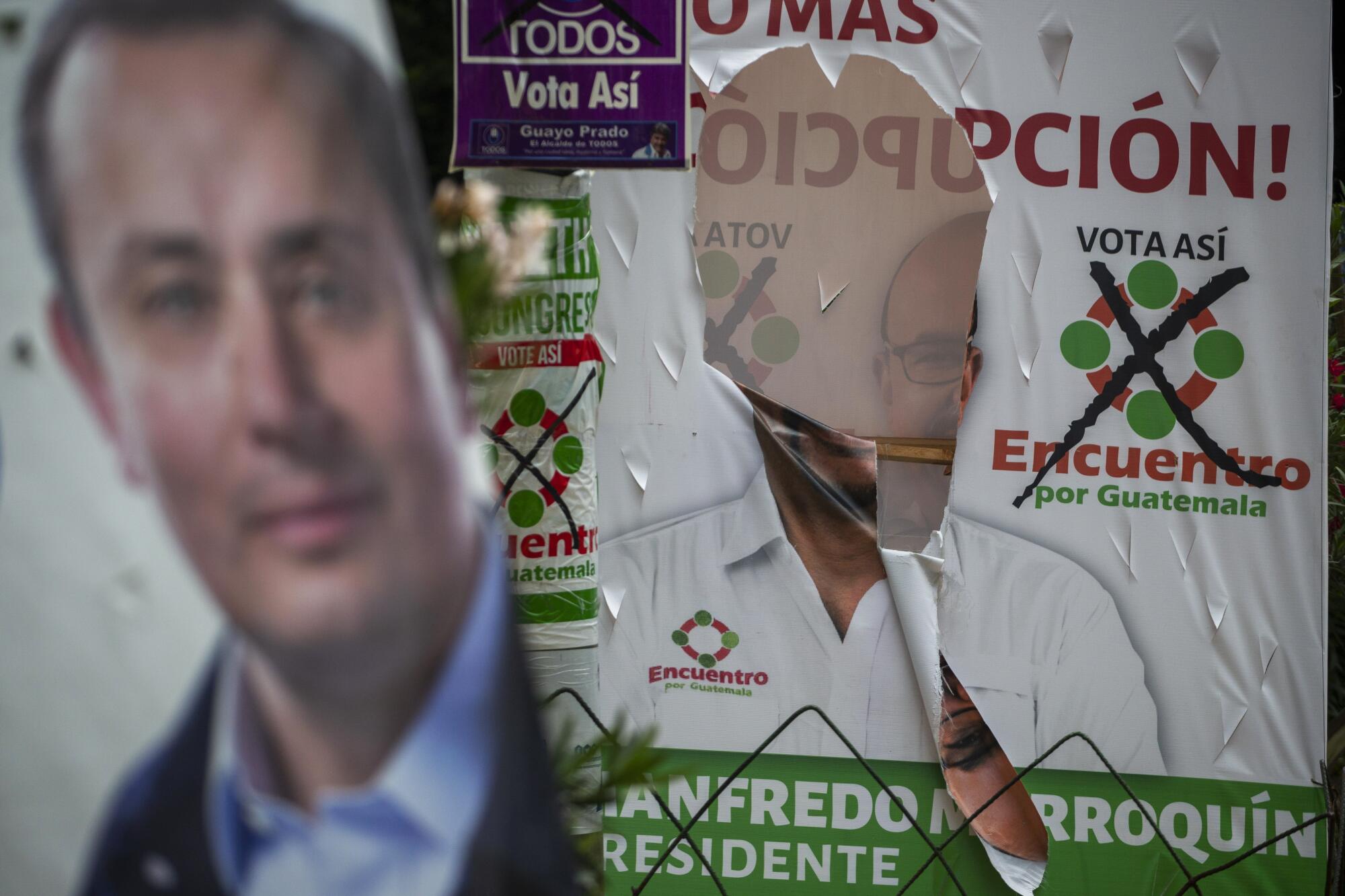

Manfredo Marroquín, an anti-corruption activist in Guatemala who met Harris there in 2021, said that she seemed sympathetic to migrants, but that it was clear “she was under pressure to show a hard line on immigration.”

Harris, he said, had been saddled with the hopeless task of quickly curtailing migration from a long-troubled region where leaving to work in the U.S. has long been one of the only escapes from poverty.

He termed her assignment in the region “mission impossible.”

::

When Harris became the district attorney of San Francisco in 2004, she quickly established herself as a supporter of immigrant rights. She prosecuted an unlicensed contractor in a wage theft case involving day laborers and criticized proposed federal legislation that would have made helping people without legal status a felony.

She continued that bent as state attorney general, most notably opposing a Republican bill in Congress that would have withheld federal funding from California police who complied with the state’s sanctuary law that limited how long they could hold migrants for transfer to immigration custody.

“When local law enforcement officials are seen as de facto immigration agents, it erodes the trust between our peace officers and the communities we are sworn to serve,” she wrote in a 2015 letter to U.S. senators. She also issued guidelines to California law enforcement agencies outlining “their responsibilities and potential liability for complying” with immigration authorities’ hold requests.

In her first official speech as a U.S. senator in 2017, Harris railed against President Trump’s executive actions targeting immigrants. “I know what a crime looks like, and I will tell you: An undocumented immigrant is not a criminal,” she said. “The truth is the vast majority of immigrants in this country are hardworking people who deserve a pathway to citizenship.”

In budget talks, she favored beefing up border security with various forms of technology but called expanding the border wall “ridiculous.”

She was the first Senate Democrat to announce she would withhold support from any deal that didn’t include a fix for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era program that protects immigrants brought to the U.S. as children from deportation, and which Trump had targeted. She introduced bills to increase oversight of immigrant detention centers and halt funds for new facilities, as well as to provide legal representation for immigrants in deportation proceedings.

As she campaigned for the Democratic presidential nomination ahead of the 2020 election, she was firmly to the left of Biden and many of her rivals on immigration issues. She made headlines when she said that, as president, she would consider overhauling the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. At the time, some on the left were advocating for the agency to be abolished.

Immigration enforcement has long been the domain of the federal government. Texas is trying to change that.

By the time Harris and Biden entered the White House, a political crisis was brewing at the U.S.-Mexico border, with the number of migrants entering the country steadily rising.

Biden tapped Harris to lead a high-profile response that bet heavily on improving conditions in Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, the so-called Northern Triangle. The White House wanted Harris to enlist governments and private companies to fund economic and social programs throughout the region.

Harris got to work, soliciting donations from various countries, including Ireland, Japan and South Korea. Her office announced initiatives by companies, including Nespresso, that pledged to expand their collaboration with small-scale coffee farmers in hopes that more economic opportunity would diminish the allure of heading north.

But Harris seemed wary. While Biden had enthusiastically taken the lead on diplomacy in Latin America when he served under President Obama, traveling to the region 16 times during his eight years as vice president, Harris seemed to sense the political danger of being identified with such a divisive topic as immigration.

Amid Republican efforts to paint immigration as a threat, 55% of U.S. adults now believe that “large numbers of immigrants entering the United States illegally” are a critical threat to U.S. vital interests, according to a recent Gallup poll. The poll showed that immigration had surged to the top of the issues that voters cared most about — more than the economy or inflation.

::

Harris’ fears were confirmed by the flak she received in Guatemala after warning migrants to stay home.

“For Guatemalans, ‘Do not come’ was similar to Trump constructing a wall,” said José Echeverría, the director of the Movimiento Cívico Nacional, who was among the civic leaders who met with Harris on that trip. He said he was disappointed that White House officials never followed up with him and other community leaders.

After the visit, the vice president’s office announced an additional $170 million in U.S. aid for Guatemala, including funding for job training, agricultural research, law enforcement reform and other initiatives.

But Marroquín, the anti-corruption activist, said aid and initiatives from private companies seldom reach the country’s needy as effectively as remittances sent from migrants abroad.

“This aid hardly impacts anyone in the communities — it’s not enough, it’s delayed, or it never arrives,” he said.

Will Freeman, a fellow for Latin America studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, said even the best-intentioned programs struggle to address what drives migration.

“The root cause is the disparity in the labor markets between the U.S. and the Northern Triangle, and there’s no workable strategy that’s gonna close that gap,” Freeman said. “Do you think you’re gonna make $20-an-hour jobs common in Guatemala?”

Still, Freeman said Harris’ approach was a welcome shift from that of the Trump administration, which withheld aid from Central American countries in 2019 in retaliation for what he called their lack of help in stanching the flow of migrants to the U.S. border.

“The Trump administration basically treated these countries as, you know, the source of a problem,” Freeman said. “Their entire policy was punitive.”

He and others applauded Harris’ efforts to fight corruption and promote democracy — which were not priorities for Trump.

Depending on whom you ask, the federal immigration app CBP One is a solution to the border crisis, a human rights violation or a ploy to let anyone into the U.S.

Harris shunned Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who after leaving office was arrested, extradited to the U.S. and sentenced to 45 years in prison for drug trafficking. She did the same with Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, who defied the constitution to stay in power a second term and alarmed civil rights advocates with widespread arrests and detentions as part of a crackdown on gangs.

When Guatemalan anti-corruption crusader Bernardo Arévalo won his country’s presidential race last year, the White House fought efforts by his political enemies to bar him from taking office. But when he finally did, many Guatemalans were disappointed that Harris skipped his inauguration.

The results of Harris’ work are difficult to measure, analysts say.

The three countries in Harris’ portfolio showed significant drops in annual migration, from more than 700,000 border arrests in the 2021 budget year to fewer than 500,000 in 2023.

But total apprehensions at the border during the Biden presidency hit record numbers, with 2.2 million in 2022.

The peak during the Trump administration was 850,000 in 2019, though experts say the Biden figures undoubtedly include more people who crossed the border multiple times, thanks to a pandemic-era policy that rapidly returned migrants to Mexico, from where they could try again.

The increase during the Biden years was fueled by people fleeing Venezuela, Nicaragua, Cuba and Haiti, who together accounted for 583,000 border arrests in 2023.

Some say the administration miscalculated, choosing a narrow strategy that failed to anticipate the shifting nature of migration. “Migration was becoming this completely different thing,” Freeman said.

Amid growing criticism about the border from Republicans but also from Democratic leaders in blue states such as New York, where hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers arrived in recent years, Biden enacted an executive order June 4 limiting asylum access at the southern border.

Since then, overall arrests of migrants have decreased by more than half, reaching the lowest point since Biden took office.

Immigration agents arrested fewer than 84,000 people in June, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which was down from 95,000 arrests in June 2019, the last year before the pandemic.

“Border crossings are lower today than when the previous administration left office,” Biden said in an Oval Office address on Wednesday about his decision to drop his run for reelection.

::

Since Harris became the leading Democratic candidate, she has avoided the topic of migration.

But Rep. Adam B. Schiff, a Burbank Democrat running for Senate, said in an interview with The Times that Harris will be able to effectively counter the Republican criticisms of her record — and the Biden administration’s record — on immigration.

“She can articulate what she and the president are doing to secure the border, to beef up resources, about how in fact Donald Trump was the one who tried to kill any work that might have come out of Congress on the issue,” he said.

Harris, who like Schiff is a former prosecutor, has “a case to make” about how Republicans “have demonstrated they have no interest in solving the problems at the border,” Schiff said.

“They only have an interest in exploiting them,” he added.

It’s clear that Harris campaign messaging on immigration will be distinct from that of Trump. The Republican Party’s official platform says that if he wins, his administration will “carry out the largest deportation operation in American history,” removing “millions of illegal migrants.”

But given the electorate’s concerns about illegal immigration, it remains to be seen how far Harris will go in the other direction.

For years, women have made inroads into Mexican politics thanks to a 2019 constitutional reform requiring gender parity in all elected posts.

Salas, the California activist, remembers Harris as a fearless leader who championed immigrant rights during the toughest moments of the Trump administration. “She told us we could depend on her,” Salas recalled.

She was disappointed when, as vice president, Harris’ voice on the issue suddenly became “muted.”

If Harris wins the presidency, Salas wants her to “be bold on executive action,” using her power to defend immigrants in the same way Trump used his power to target them. She also wants Harris to push for immigration reform to regularize the status of undocumented migrants, many of whom have lived in the U.S. for decades.

“I know her and I know how competent and knowledgeable she is on this issue,” Salas said. “I saw how much she fought for us when we truly needed somebody that would stand up for us.”

Times staff writers Linthicum and McDonnell reported from Mexico City, Castillo from Washington and Rector from San Francisco. Staff writer Noah Bierman in Washington and special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.