The ‘Appeal to Heaven’ flag involved in Alito controversy evolved from Revolutionary War symbol to banner of the far right

- Share via

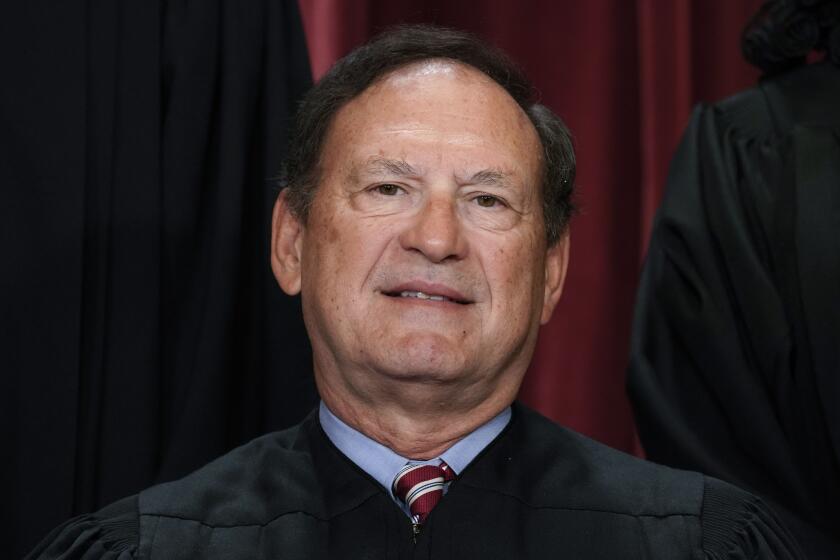

WASHINGTON — U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. is embroiled in a second flag controversy in as many weeks, this time over a banner that in recent years has come to symbolize sympathies with the Christian nationalist movement and the false claim that the 2020 presidential election was stolen.

An “Appeal to Heaven” flag was flown last summer at Alito’s beach vacation home in New Jersey, according to the New York Times, which obtained several images showing it on different dates in July and September 2023. The Times previously reported that an upside-down U.S. flag — a sign of distress associated in recent years with supporters of the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection — had flown outside Alito’s Alexandria, Va., home less than two weeks after the violent attack on the Capitol.

Some of the rioters carried the inverted American flag or the Appeal to Heaven flag, which shows a green pine tree on a white field. The revelations have escalated concerns over Alito’s impartiality and his ability to objectively decide cases currently before the court that relate to the Jan. 6 attackers and Trump’s attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Alito has not commented on the flag at his summer home.

Here is the history and symbolism of the Appeal to Heaven flag.

What are its origins?

Ted Kaye, secretary for the North American Vexillological Assn., which studies flags and their meaning, said the Appeal to Heaven banner dates to the Revolutionary War. Six schooners outfitted by George Washington to intercept British vessels at sea flew the flag in 1775 as they sailed under his command. It was the maritime flag of Massachusetts from 1776 to 1971, he said.

According to Americanflags.com, the pine tree on the flag symbolized strength and resilience in the New England colonies and the words “Appeal to Heaven” stemmed from the belief that God would deliver the Colonists from tyranny.

Photos showed an upside-down flag at the home of Justice Alito. He says he is a victim of unfair attacks.

How has its symbolism changed?

There are a few reasons people fly Appeal to Heaven flags today, said Jared Holt, a senior analyst at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a London-based think tank that tracks online hate, disinformation and extremism.

Some identify with a “patriot” movement that obsesses over the Founding Fathers and the American Revolution, he said. Others adhere to a Christian nationalist worldview that seeks to elevate Christianity in public life, and which has often been associated with white nationalism.

“It’s not abundantly clear which of those reasons would be accurate” in this situation, Holt said. But he called the display outside Alito’s home “alarming,” saying those who do fly the flag are often advocating for “more intolerant and restrictive forms of government aligned with a specific religious philosophy.”

The Appeal to Heaven flag was among several banners carried by Jan. 6 rioters, who also favored the Confederate flag and the yellow Gadsden flag, with its rattlesnake and “Don’t Tread on Me” message, said Bradley Onishi, author of “Preparing for War: The Extremist History of White Christian Nationalism.”

“That’s the family,” he said.

Justices uphold a redistricting map drawn by South Carolina’s Republican Legislature and overturn a lower court ruling that called it a “stark racial gerrymander.”

What about Mike Johnson?

House Speaker Mike Johnson displays the flag in the hallway outside his office next to the flag of his home state, Louisiana.

Johnson, a Republican, told the Associated Press he did not know the flag had come to represent the “Stop the Steal” movement.

“Never heard that before,” he said.

The speaker, who led one of then-President Trump’s legal challenges to the 2020 election, defended the flag and its continued use despite the modern-day symbolism around it.

“I have always used that flag for as long as I can remember, because I was so enamored with the fact that Washington used it,” Johnson said. “The Appeal to Heaven flag is a critical, important part of American history. It’s something that I’ve always revered since I’ve been a young man.”

He added: “People misuse our symbols all the time. It doesn’t mean we don’t use the symbols anymore.”

Johnson said he had never flown the U.S. flag upside down, as Alito did, and he declined to assess the justice’s situation and whether raising the flags at his home was appropriate.

But he called the criticism of the Appeal to Heaven flag “contrived.”

“It’s nonsense,” he said. “It’s part of our history. We don’t remove statues and we don’t cover up things that are so essential to who we are as a country.”

Should Alito recuse?

The House Democratic whip, Rep. Katherine Clark of Massachusetts, said in a statement that the display of the Appeal to Heaven flag at an Alito home was “not just another example of extremism that has overtaken conservatism. This is a threat to the rule of law and a serious breach of ethics, integrity and Justice Alito’s oath of office.”

She called for Alito to recuse himself from cases related to Jan. 6 or Trump.

There’s a clear difference between the House speaker displaying the flag outside his office and a Supreme Court justice flying it and the upside-down American flag outside his homes as the court is deciding cases involving issues those flags have come to symbolize, said Alicia Bannon, director of the Judiciary Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. Alito’s actions don’t “just cross the line,” she said. “They take you out of the stadium and out of the parking lot.”

Alito and the court declined to respond to requests for comment on how the Appeal to Heaven flag came to be flying and what it was intended to express. Alito has said the upside-down American flag was briefly flown by his wife during a dispute with neighbors and that he had no part in it.

Another blow to the court’s reputation?

The Supreme Court already was under fire as it considers unprecedented cases against Trump and some of those charged for the attack on the Capitol.

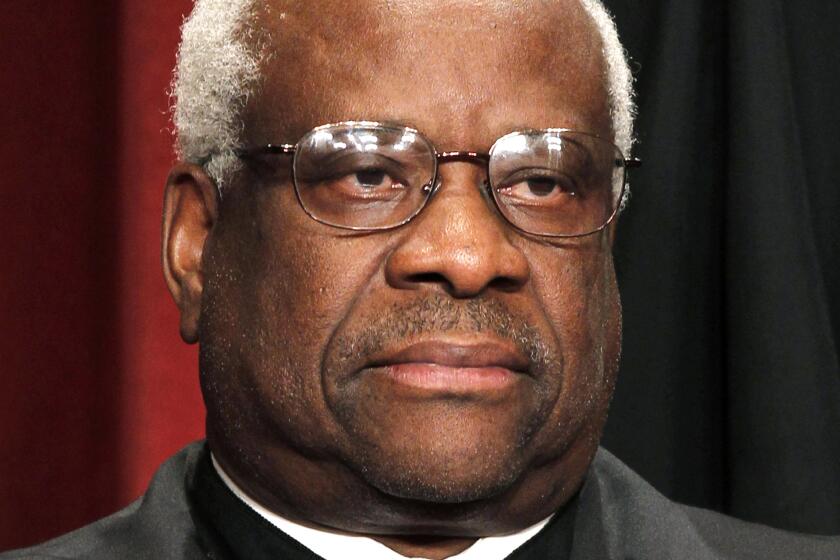

At issue is that the high court does not have to adhere to the same ethics codes that guide other federal judges. The Supreme Court had long gone without its own code of ethics, but it adopted one in November 2023 in the face of sustained criticism over undisclosed trips and gifts from wealthy benefactors to some justices, including Alito. But the code lacks a means of enforcement.

Justice Antonin Scalia’s impact on the Supreme Court includes forging the way for justices to accept free trips —something that has entangled Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

The federal code of judicial ethics does not universally prohibit judges from involvement in nonpartisan or religious activity off the bench. But it does say that a judge “should not participate in extrajudicial activities that detract from the dignity of the judge’s office, interfere with the performance of the judge’s official duties” or “reflect adversely on the judge’s impartiality.”

Jeremy Fogel, executive director of the Berkeley Judicial Institute at the UC Berkeley Law School, said the flag revelations lead to questions about whether Alito can be impartial in any case related to Jan. 6 or Trump.

A 2004 Los Angeles Times report disclosed gifts to Justice Thomas from rich Texan Harlan Crow. In response, Thomas stopped disclosing them.

“Displaying those particular flags creates the appearance at least that the justice is signifying agreement with those viewpoints at a time when there are cases before the court where those viewpoints are relevant,” he said.

A March AP/NORC poll found that only about one-quarter of Americans think the Supreme Court is doing a somewhat or very good job upholding democratic values. About 45% think it’s doing a somewhat or very bad job.

Fields, Mascaro and Amiri write for the Associated Press. AP writer Ali Swenson in New York contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.