- Share via

CULIACAN, Mexico — Emilia is a 2-year-old spider monkey who wears jeans, crop tops and Armani perfume.

A popular TikTok account documents her busy life: trips to the spa, gym and church, as well as elaborate birthday parties for other pet monkeys, where she might cavort with friends in an inflatable bounce house and smash her face into a carrot cake.

It is illegal in Mexico to own spider monkeys, which are critically endangered and trafficked from jungles in the country’s south. That hasn’t stopped people in the northern city of Culiacan, home to one of the world’s most powerful drug cartels and known for ostentatious displays of wealth.

“So many people here have them,” said Zulma Ayala, a 34-year-old florist who was gifted Emilia two years ago. “It’s fashionable. It says: ‘I have the money to have a monkey.’”

Primates aren’t the only exotic animals popular here. At private homes and ranches in Culiacan and across the rest of rugged Sinaloa state, it is not uncommon for people to keep lions, tigers and, yes, even bears.

The practice began decades ago as local narcos sought to emulate Colombian drug lords like Pablo Escobar, who famously stocked private zoos with giraffes, elephants and hippos. Now, wealthy people of all stripes in Mexico own exotic animals.

They walk tigers on leashes down city streets and parade them in the backs of luxury cars. Socialites have formed private “monkey clubs,” gathering for extravagant Christmas posadas and pool parties. The internet fuels the phenomenon, with influencers showing off their exotic pets and social media making it easier than ever to acquire the animals. A quick search of Facebook turns up local vendors selling lion cubs, lemurs and rare white tigers.

One of the few veterinarians in northern Mexico trained to treat exotic animals is Roy Quintero, whose patients include Emilia the spider monkey. His phone rings often with calls from anxious pet owners.

Once he was asked to treat a monkey that had accidentally consumed fentanyl. (He managed to save it.) Another time he helped an owner track down a tiger that had escaped into a canyon.

Then there was the time Quintero found himself high in the sky in a propeller airplane alongside a sedated 300-pound tiger, which he was helping to transport.

“I was terrified he was going to wake up,” Quintero said.

Quintero, who makes a practice of never asking his clients what they do for work, said he has been threatened with death several times, including once when he was unable to save a monkey that died after consuming a toxin.

His job is risky and — he’s the first to admit — ethically murky.

He fell in love with animals as a poor kid in nearby Sonora state, where he began tending goats at age 9. Decades spent working in zoos deepened his knowledge of how to heal uncommon animals, as well as his conviction that most people simply aren’t equipped to care for creatures meant to thrive in the wild.

“It’s really easy to acquire one,” he said. “It’s much harder to feed them right, give them enough space and give them the care they need.”

But when his phone buzzes and an owner asks for help, Quintero almost always gives in. A father of four, he has mouths to feed. And he can’t stand the thought of an animal in need.

“I don’t like it,” he said. “But if I don’t treat them, who will?”

On a recent afternoon, Quintero threw a medical bag into the back of his Isuzu pickup and headed out of town.

He had spent the morning at his Culiacan clinic checking up on several patients, including a 4-year-old spider monkey named Elisa who had been hit by a car after escaping from her owner’s home. Quintero had performed a complicated reconstructive surgery on the monkey’s hand, and she was slowly healing.

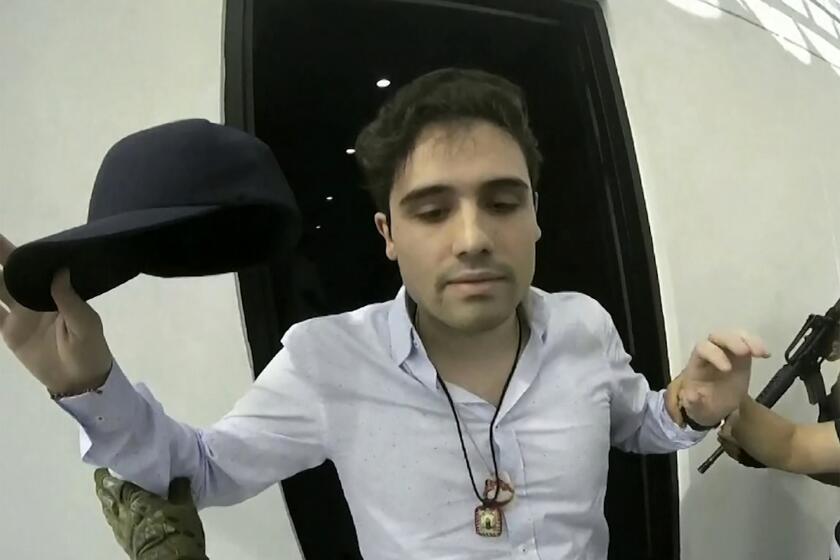

In Mexico stronghold of Sinaloa cartel, armed men burn vehicles, storm airport to try to prevent capture of drug lord Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s son.

Dressed in khaki pants and work boots, Quintero kept a wide-brimmed safari hat on the seat next to him — part of his security strategy.

The uneasy peace that held while Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán led the Sinaloa Cartel shattered several years ago when he was sentenced to life in a U.S. prison. Since then, other leaders of the cartel have battled for supremacy while being hunted by the Mexican government. Quintero hopes that if he is stopped by the military or drug traffickers, donning the hat will broadcast his identity: a harmless veterinarian just trying to get to work.

He passed a small Catholic chapel set against the scrubby landscape and an elaborate altar to Santa Muerte, a figure revered among drug traffickers here. He rolled through an army checkpoint, waving to fatigue-clad soldiers, and by a road sign riddled with bullet holes.

Finally, he arrived at the ranch, tucked off a main highway, down a dirt road.

As crime engulfs many Mexican states, immigrants who’ve saved to retire there are reevaluating ties to home — and whether returning is worth the risk.

More than 30 big cats paced inside cages, some of which were the size of a studio apartment. A bald eagle flapped around an enclosure. A wolf-dog hybrid scampered about. Cacophony filled the humid air: the mad squawking of parrots, the grunts of emus, the occasional roar of a lion.

Agustín Félix, a 26-year-old in tight jeans, expensive sneakers and a trucker hat, greeted Quintero with a slap on the back.

Félix is the son of a businessman who owns a transportation company and a cemetery. His father used to collect classic cars but several years ago started acquiring uncommon animals.

Though owning spider monkeys is prohibited in Mexico, buying and selling many other exotic species is legal as long as they are not taken from the wild. That includes lions, tigers and jaguars.

Owners must obtain approval from a government agency and show evidence that the animal was born in captivity. Laws stipulate that the animal must be safely confined and treated with respect, although a shortage of inspectors results in lax enforcement.

Once his father began acquiring large felines, Félix said, friends started asking how they could get their own.

“Here, people see something new, and then everyone wants it.”

As they toured the ranch, Quintero sought to put the animals at ease by imitating their sounds, emitting a low whistle to the jaguars and blowing air through his lips at the tigers. Félix handed his phone to a friend and posed alongside the animals for pictures for social media.

After he and Quintero inspected a pair of former circus bears that had recently been donated to the ranch, Félix showed the vet his newest prize: a Bengal tiger cub born there a few months earlier.

The cub had an unusually narrow face, which Quintero said was likely the result of inbreeding, a common occurrence given the lack of genetic diversity among big cats in captivity. The cub also looked malnourished.

“You have to supplement his diet,” Quintero said, recommending omega-3s and taurine, an amino acid critical for tigers that is also a main ingredient in energy drinks.

“Will Red Bull work?” Félix joked. His friend laughed heartily. Quintero struggled to crack a smile.

Back on the road, Quintero said he was feeling down — and ready for an after-work drink.

“I’m depressed all the time,” he said. “This is an animal that is under threat of extinction, and it’s somebody’s toy.”

Wealthy rulers throughout history, from Carlos III of Spain to Moctezuma, the ruler of the Aztec Empire, have kept menageries.

Today’s narcos are likely to be influenced more by the zoos of Colombian traffickers or films like “Scarface,” the gangster flick whose protagonist, Tony Montana, famously kept a tiger as a pet.

At a sprawling animal sanctuary on the outskirts of Culiacan on a recent afternoon, a regal tiger blinked in the sun. The animal had survived a gun fight, said Ernesto Zazueta, director of the Ostok Sanctuary, and had battle scars on its face and shoulder.

“They shot him two or three times,” Zazueta said.

Many of the hundreds of animals at this sprawling reserve were confiscated after police raids on the homes of traffickers. Others were abandoned because their owners couldn’t care for them or feared that they would bring unwanted attention from authorities. Zazueta pointed to a puma huddled near the back of its cage. It had been dumped, left chained to a post in the center of a nearby town.

Mexico is rife with stories about exotic narco pets. There was the recent U.S. federal indictment that accused the sons of “El Chapo” of feeding their enemies to tigers. (Their lawyers denied it.) Or the spider monkey found dead in a cartel shootout in Mexico state, dressed in a tiny bulletproof vest. A corrido singer quickly penned a ballad about the fallen primate.

Just as other trappings of narcoculture have proliferated throughout Mexican society — from norteño fashion to the new generation of drug ballads that top national charts — so too has the ownership of exotic animals.

Four banners appeared simultaneously in different parts of Tijuana this week warning the singer to cancel his planned concert on Oct. 14.

“For rich people, it gives them a sense of power,” said Zazueta. “The more powerful the animal, the more powerful it makes them feel.”

His sanctuary is working to import from Colombia several descendants of Escobar’s famous “cocaine hippos,” which were abandoned into the wild after his death in 1993 and have reproduced rapidly, posing environmental challenges.

While Sinaloa’s wealthy men gravitate toward tigers and lions, Zazueta said, their female counterparts tend to collect spider monkeys.

Local influencers and their pampered primates dominate TikTok. The social media stars include a monkey named Kira Sophia, who appeared in a music video and whose TikTok boasts nearly 25,000 followers. A clip of her lavish first birthday party, featuring a live band and a procession of horses, was viewed more than 2 million times.

Many people here treat their monkeys like children, swaddling them in cribs at night and dressing them in diapers — cutting a hole for their long tails to peek through. Some monkeys wear name-brand clothing and sport gold chains around their thin, hairy necks.

But behind the scenes, having a monkey is a lot of work. Just ask Emilia’s owner.

Ayala has retrofitted her elegant home with monkey bars and ropes to keep Emilia from swinging from the television or ceiling fans.

She isn’t quite sure how to deal with Emilia’s occasional outbursts of aggression — recently the monkey took a bite out of her teenage son’s chest — and checks in frequently with Quintero, the vet, to make sure she’s feeding her pet the right mix of fruits, minerals and protein.

Her son sometimes jokes that Ayala spends more time caring for Emilia than for him. “And he’s right,” she said.

Ayala changes Emilia’s diapers eight times a day. She gives the monkey long baths — Emilia loves warm water — followed by a blow dry and a spritz of Armani perfume. She takes Emilia to the store and to meetings, graciously stopping to let strangers pose with her for photographs.

Sometimes it’s so much work that Ayala doesn’t have time for a shower. Sometimes, after a particularly hard day, she finds herself weeping.

1

2

3

1. Zantiel Emilio Zuniga, 15, and his mother, Zulma Ayala, change Emilia’s clothes. 2. Emilia is often dressed in jeans and crop tops. 3. Ayala takes the monkey on shopping trips and to business meetings.

“She’s like a child, but three times the work,” Ayala said on a recent warm evening as Emilia scampered around, playing with a helium balloon and an empty plastic bottle.

Cuddling Emilia at night makes everything worth it, Ayala said. But sometimes it makes her sad knowing that Emilia will never grow up.

“I call her my little girl,” said Ayala. “But she’s never going to stop being a monkey.”

Each spring, hundreds of gay cowboys gather in Zacatecas for a convention that celebrates sexual freedom and romanticizes Mexico’s rural past.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.